ADAM FUSS

MICHAEL SAND

The industrial-strength metal door opens into a dark, cluttered room, which leads to a larger, windowless warehouse space that is Adam Fuss’s studio. Although his current work involves laying fresh rabbit intestines on photographic paper for extended periods of time, the air reveals nothing other than the smell of photo chemistry.

The front room contains an aging refrigerator, a large table on which rests a work-in-process (tightly wrapped in black paper), and a wall of metal bookshelves holding Fuss’s “library”: a Ralph Eugene Meatyard monograph, Joan Mitchell’s book of pastels, The Art of Photography, and a hodgepodge of assorted catalogs and magazines. Somewhere in the mess of papers and books is a copy of Paul Caponigro’s out-of-print sunflower monograph.

In the rear of the studio a monstrous, spiderlike contraption made of garden hoses and metal piping hangs from the ceiling. It is a device Fuss built to create a sheet of falling water for a series of images he plans someday to make. This gnarled sculpture takes up a fair amount of room, and was one reason he rented the warehouse to begin with. Fuss is an incurable experimenter.

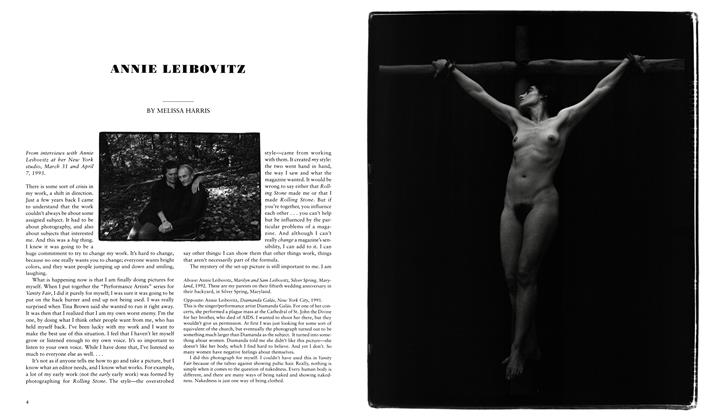

A black form lopes around the studio. A cat? No, it’s Jacob, Fuss’s beloved pet rabbit. This is not a sick joke; he does not plan to eviscerate the creature for some future project. And as we talk, Fuss takes Jacob on his lap and strokes the rabbit’s long ears lovingly.

Over a year ago, at a time of wrenching emotional turmoil in his life, Fuss began “Details of Love,” a recent series of images. The work that was the prototype for this project is a color photogram depicting two rabbits in profile, face to face, surrounded by a luminous multicolored tangle of abstract squiggles. It is called, simply, Love. The squiggles that are the basis of all the images in this series are rabbit intestines; the painterly depth and range of colors are the result of an unlikely chemical interaction between the fresh innards and Cibachrome paper.

Fuss’s peculiar form of personal expression begins to make sense when his art is viewed in retrospect. From this angle, “Details of Love” can be seen as the “natural” product of a decade of relentless technical photographic experimentation—from his haunting early pinhole photographs, taken in museum galleries after hours, to near-invisible portraits of children that slowly emerge from a pitch-black background, to unique color photograms often involving organic materials.

Fuss was first drawn to photography at school in England in the 1970s. “I was attracted to photography because it was technical, full of gadgets, and I was obsessed with science. But at some point around fifteen or sixteen, I had a sense that photography could provide a bridge from the world of science to the world of art, or image. Photography was a means of crossing into a new place that I didn’t know.”

He was intrigued early on by a demonstration of the possibilities offered by the pinhole camera. Its sheer simplicity convinced him that good pictures, truly imaginative pictures, resulted from the creativity of the photographer, not necessarily from the sophistication of the equipment.

As Fuss describes it, his progression from the single-lens-reflex to the pinhole camera to the photogram was a process of gradual internalization—of the outside world coming closer to the film plane and the film in turn insinuating itself into the artist and his subjects. In a twist on Christopher Isherwood’s famous “I am a camera,” Fuss sees his “Details of Love” as being “inside the camera, but also, I feel, inside my body. . . . It’s not literally medical photography, but the subject matter derives from a sort of internalness. Yes, it’s also taking place inside this dark space.”

Asked if he consciously set out to explore cameraless photography, Fuss reacts with an almost knee-jerk negative response. His first photogram, he insists, was the result of an accident. While Fuss was taking a pinhole photograph using a homemade cardboard-box camera, the opening that served as the camera’s lens was accidently closed off. However, light leaked in from a corner of the box. It struck the color film at a sharp angle, resulting in a graduated color field dotted with the elongated shadows of dust particles floating around the interior of the box. Since there was no lens, strictly speaking, Fuss regards the image as his first photogram. “Light played across the film. . . . When I processed it, I saw this world, this other world of image that I was unaware of. And that showed me that I didn’t need the camera any more.”

Soon after this discovery he began placing a variety of objects directly onto Cibachrome paper and exposing them to light: brightly colored balloons, which allowed some light to pass through them; the yolk of an egg; long, wiry fiddleheads; sunflowers, in full glory and in various states of decay; stained glass—the list goes on. He also made photograms of movable subjects: psychedelic spirals of light created by swinging a flashlight from a pendulum over photosensitive paper, snakes slithering through sand, and babies in pools of water. Fuss claims that all of these experiments are still in a process of revision and refinement.

As with the very first photogram, chance is partly responsible for Fuss’s current work with rabbit intestines. During the creation of one of the snake images, the reptile’s bodily needs took over and it relieved itself onto the Cibachrome paper. When Fuss developed the print, he discovered that the snake’s fluids had caused a chemical reaction with the agents on the photo-sensitive paper, which resulted in a brightly colored stripe in the middle of the image. From here it was a small leap to experimenting with other organic materials interacting with the photo chemistry. A gutted fish laid out on Cibachrome produced compelling results. It was not long before he began to wonder what photograms of the internal organs of a mammal would look like.

“The rabbit was the perfect animal,” explains Fuss, “because it’s a creature that absorbs a tremendous amount of symbolism— reproduction, fertility, sacrifice, innocence.” And rabbits are also fairly easily obtainable. “It’s very hard to get the intestines from a mammal,” says Fuss, “unless you want to get a sheep or a goat and slaughter it yourself.” He could get his materials from laboratories, such as those that supply medical schools, but he finds that the chemical process in his work requires that the innards be fresh. A steady reserve of rabbit intestines from a local restaurant supplier allows Fuss to continue his work.

The photograms that involve plants and animals seem not to depict—they invoke the moment of photographic creation, and the life of the organic material, with an eerie immediacy.

In order to get the desired effect, Fuss experiments with laying the intestines on photographic paper for varying lengths of time— from a few hours to a full day and night—often moving them art ind in the dark. The whole setup is then exposed to a flash of light from a hand-held strobe. The longer the “guts” (this is how Fuss generally refers to his working materials) lie on the paper, the more they eat into its surface, destroying the emulsion. Where they have been on overnight, the image is pure white, with the faint outline of the intestine. Where they have been on for only a few hours, a Technicolor impression results.

An intensity backs Fuss’s gaze as he talks about the motivations behind hi’s current work. Describing Love, he alludes alternately to its emotional underpinnings and to his intellectualized artistic reaction: “There’s a quality of line that’s figurative, and a quality of line that’s abstract, and I wanted to make a picture where these two worlds were joined, in an intimate way. ... It came initially from this tension between inside and out, and the place where these things converge.”

Part of the appeal of the photogram for Fuss is its directness. The objects depicted came into physical contact with the very paper on which the final print appears. The experience is somehow more tactile, and in the case of Fuss’s recent work, more visceral. The photograms that involve plants and animals seem not to depict—they invoke the moment of photographic creation, and the life of the organic material, with an eerie immediacy.

Fuss has several projects in development, at least in his mind, at any one time. And he frequently will previsualize complex, seemingly accidental images to a remarkable degree. His next project, he says, will be a photogram, or series of photograms, involving a skeleton, a reflective metallic circle created by a special print-toning process, a butterfly, and an egg yolk. He pictures the skeleton and the butterfly having an ephemeral, distant quality, and the egg yolk a vibrant yellow. “You have the dead body, in the dark, lunar realm, and the passage of the soul, which is represented by a butterfly. And you have this kind of rebirth or reunion, symbolized by the egg yolk.” Referring to his own role in the process, he asserts: “Adam is really just bringing these things together. He’s not making the materials. The materials already exist. Adam is just a catalyst, or an agent.”