Straightening a bowed neck: Truss Rod Operation

Here’s where you start to see that 'complications’ might be understating things a little. 😉

Last time, I introduced you to a Gibson ES-335 with a bowed neck and a split in the back where the truss rod had burst through the wood. We stepped through taking off the fingerboard to begin getting a feel for what was behind all of this.

And here we are. With the fingerboard removed, we can see the bare face. The truss rod channel is obvious here as it’s back-filled with a contrasting maple fillet.

Before we move on any further, it’s necessary for me to tangent off into a recap/primer on how these truss rods work. Bear with me — the importance of this will become clear.

Single-action truss rod operation

The ‘traditional’ adjustable truss rod is really nothing more than a length of steel round-bar. The bar gets installed in a curved channel in the guitar neck. This is the essence of the adjustable truss rod, as patented in 1923 by Gibson worker, Ted McHugh.

This curved channel is the key to the operation.

One end of the truss rod is secured in the neck and the other end has a threaded adjustment section protruding in the headstock. Tightening the adjustment nut effectively shortens the amount of rod that’s inside the neck. As this happens, the rod pushes against the channel curve, trying to straighten itself and bringing the neck with it.

Picture yourself holding a piece of string — one end in each hand. Held loosely, the string hangs in a curved shape. Keep your hands in place and have someone pull one end of the string to shorten the section between your hands and the string will straighten. That’s a reasonable illustration of the principle.

In a guitar neck, we can rout a curved channel (Fenders typically have more curve than Gibson-style instruments but a severe arc isn’t absolutely necessary). The truss rod is inserted (anchored at the body end and poking through into the headstock cavity at the other). On top of the rod, a fillet of wood is glued into the channel to keep everything in place and give the rod something to bear off as it straightens. This fillet has a corresponding curve to match that in the neck.

The truss rod channel ‘wrinkle’

Ah, if only life were simple.

The McHugh rod, described above went through some iterations along the way, although its principle remained the same. However, to make things more difficult for luthiers writing blogs there’s another way to skin this cat.

Early Les Pauls (and possibly others) had their truss rods installed in a straight-bottomed channel. No curve/arc.

“What is this craziness?” you yell. Yeah, well, I’m with you on this one. Thing is, this works. For the most part.

The rationale, as I understand it, is this:

If the rod is installed more towards the back of the neck, its operation — rather than 'straightening an arc’ like the curved-channel rod — actually applies some compression to the rear of the neck. That compression shortens the neck in that area, correcting a bow. In practice, my feeling is that the actual string-tension bow itself slightly arcs the neck and the channel so there is some ‘accidental’ curve-straightening contributing to the overall effect.

Whatever the workings, the outcome is that a flat-bottomed channel can allow a truss rod to work and correct bow.

As I’ve opened the door on my feelings, I personally prefer my truss rods be installed in a curved channel. I think it’s more effective. But, some guys at Gibson disagreed with me up until the ‘60s and I believe this still happens on some models. Who knows why? Nobody thought to check with me.

Back to our neck

To (a) ensure a good repair of the cracked portion where the truss rod burst through and (b) try to figure out why that happened and what’s going on I’ve resigned myself to removing the truss rod.

I say resigned because I have to cut that maple fillet out by hand. I don’t know exactly where the truss rod sits in the neck so I don’t want to risk trying to rout it out. Rapidly spinning router bits contacting round steel rods isn’t a recipe for Gerry’s happiness so I get a chisel and make an old-school start.

Now I’ve got the truss rod out, I can take a closer look at this neck. I checked out the depth of the truss rod channel at a number of points along its length. The results were interesting.

Initially, it looked like we were dealing with a straight/flat-bottomed channel. There’s a very slight downward angle as the channel progresses from the nut towards the end of the neck.

Then, just a bit past the octave, the channel takes a pretty steep dive deeper into the neck.

That’s a bit weird. This gives a slight backward arc to the bottom third of this rod.

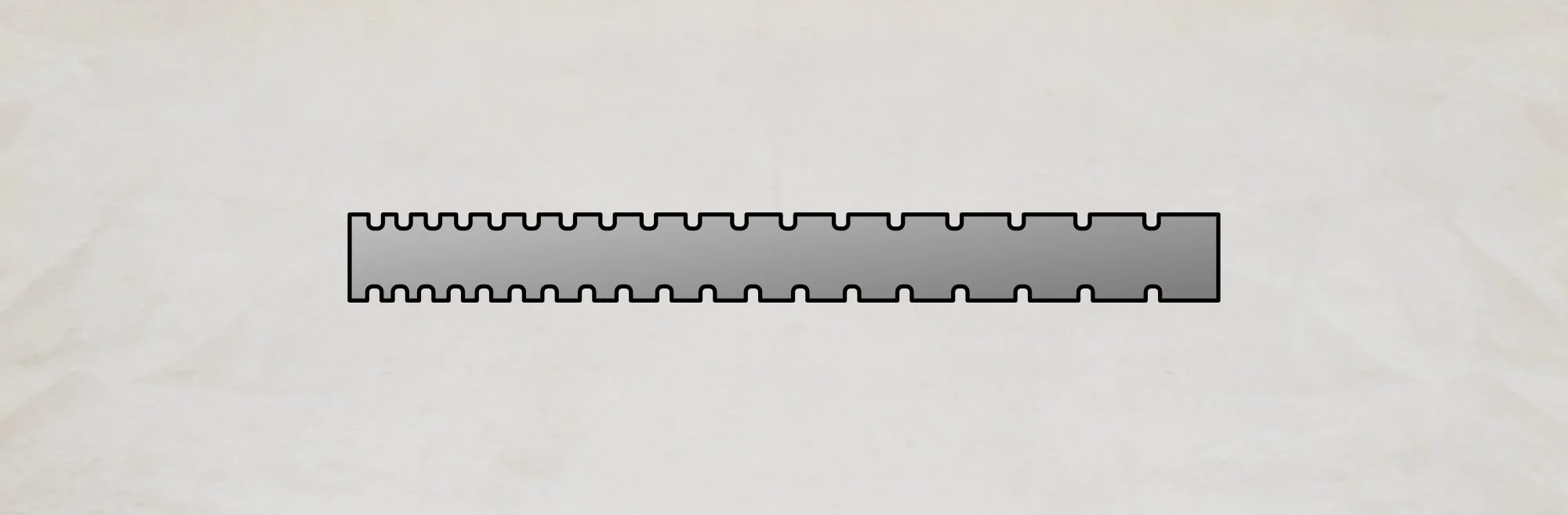

Importantly, this channel is deep. Too deep. This isn’t a massive clubby neck. With the fingerboard removed, I measured the thickness at the first fret position to about 15.1mm (.59”). With the truss rod channel cut to 14.28mm deep, that leaves around .8mm (.031”) of wood behind the rod. Even for a wood veneer, that’s pretty thin.

What all of this means is that, in my opinion, this neck was bound to have problems. The truss rod channel seems to have been cut (a) with an odd shape and (b) too deeply. This truss rod was always going to have trouble straightening neck-bow and, with so little wood behind it, was always liable to burst through as it was compressed.

It seems likely that something went awry when the channel was being machined.

Benefit of the doubt #1: This could have been missed during construction.

Benefit of the doubt #2: It’s possible that this neck remained straight against initial string-tension so that it passed a setup and QA inspection after construction. The grumpy guitar repairer in me has more trouble with this doubt-benefit.

So, that’s the problem. Since this is running long, for the solution, you’ll need to tune in next week.

This article written by Gerry Hayes and first published at hazeguitars.com