How the Orange Tower Tradition Began

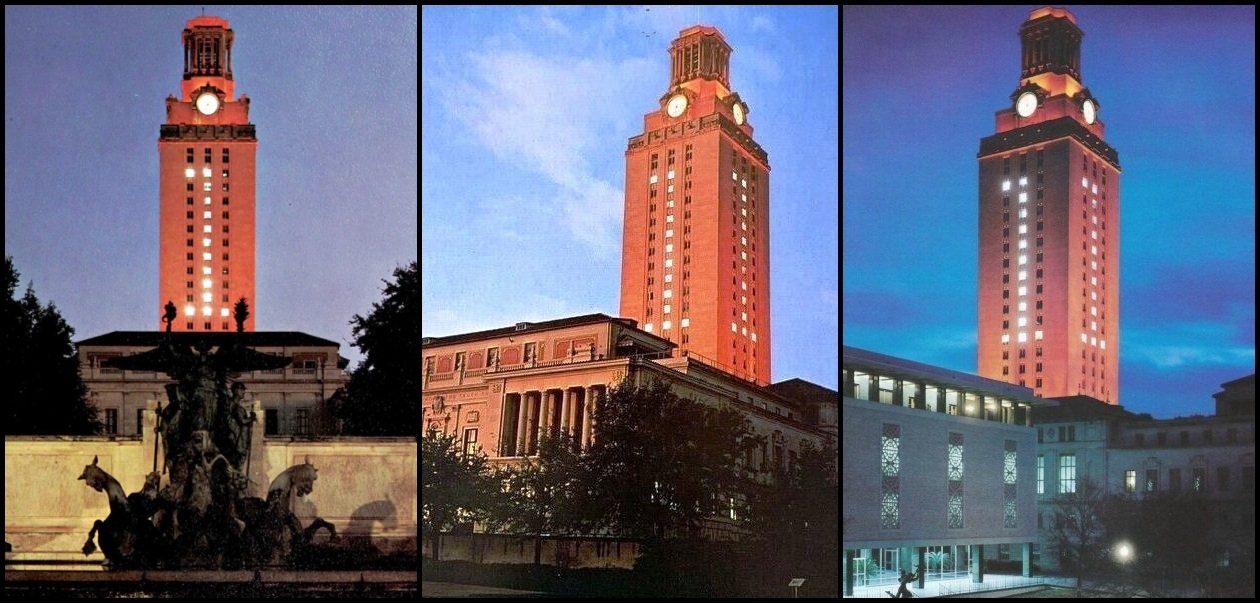

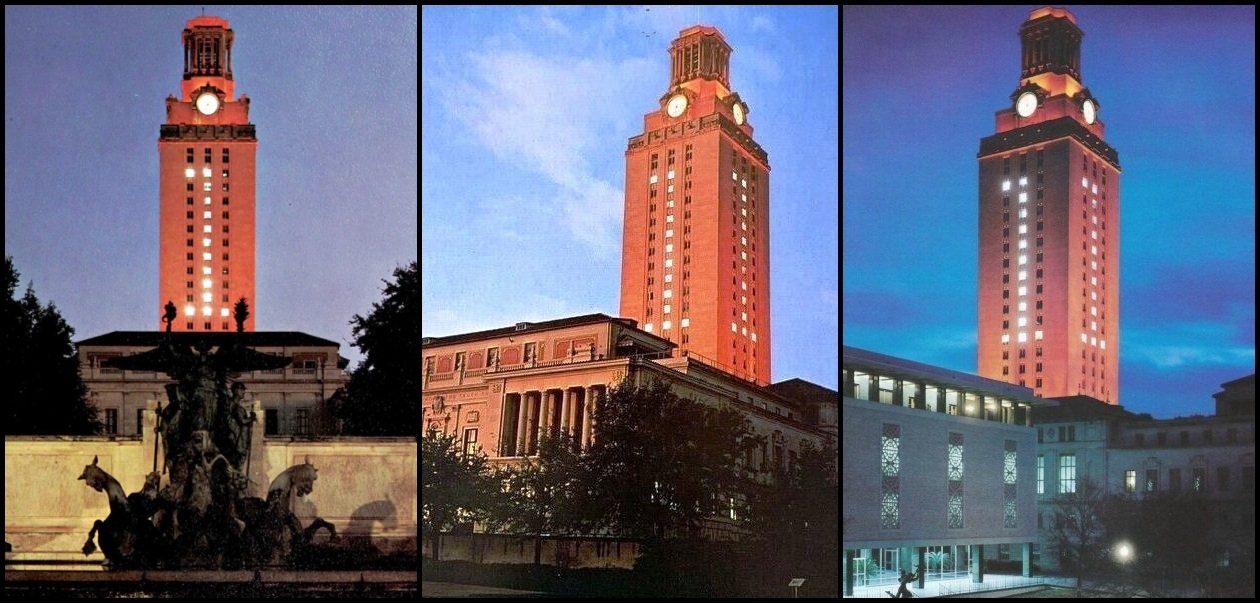

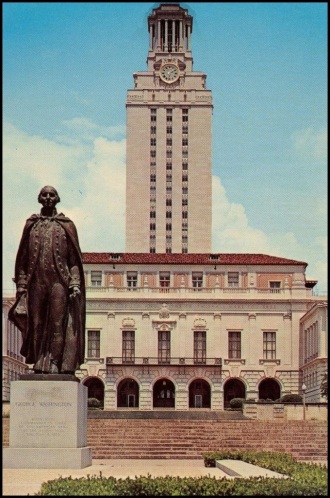

It was a night like no other. On Tuesday, October 19, 1937, as the sun dropped behind the western hills, the azure sky darkened to dusk, and a full moon peeked above the eastern horizon, floodlights illuminated the University of Texas Tower for the first time. Austin was changed forever.

Frank White and Bob Wilkinson, reporters for The Daily Texan student newspaper, stood on the Main Mall in front of the Tower, looked up and took in the scene, but struggled to express what they saw. They eventually agreed upon the phrase “majestic splendor” for the following morning’s issue, but were open to suggestions. “If you can think of any better description for the bath of orange and white light that flooded the Library Building Tower last night for the first time, you should be writing this story. Seriously, the splendor was majestic; so majestic, in fact, that students seeing it with us were entranced with its colorful beauty, and found no words to describe it.”

The splendor was just beginning. For the University, the Tower was an instant icon, purposely designed to be the seminal landmark of the campus. As architect Paul Cret explained: “In a large group of buildings, be it a city, a world fair, or a university, there is always a certain part of the whole which provides the image carried in our memory when we think of the place.” The Tower was meant to be that image.

For the citizens of Austin, the Tower was a radical addition to the city’s skyline. It was the first building to rise higher than the venerated dome of the Texas Capitol, which generated more than the usual share of controversy.

The Tower was also built 20 years earlier than planned. It arrived in 1937, at a time when modern, lofty buildings had just come of age in American cities, along with a popular new development: the use of floodlights. Sometimes described as “painting with light,” architects in the 1920s and ‘30s widely experimented with external lighting on the walls of high-rises, often with dramatic colors and dazzling effects. This, in turn, influenced what was a pivotal decision to install floodlights on the Tower.

The Tower lights, especially the use of orange and white, brought with them a great surprise. The sight of the University’s colors, displayed on such a grand scale against the backdrop of a Texas night, transformed the Tower into something more than a landmark. The lights added a new and unexpected dimension to the building, both in its nighttime appearance and in the swell of public affection at the sight of it. Had construction of the Tower waited until the 1950s as intended, it would have been built when new stylistic trends in architecture minimized the use of external lighting. The Tower might not have been floodlit at all, and the University could have missed out on one of its best-loved traditions.

~~~~~~~~~~

In the mid-1930s, construction of the UT Tower was front page news. The Austin American-Statesman described it as “luxurious and palatial,” while the Texan waxed poetic: “Like the shining spire of some fabled city, the new Library Tower will rise in the air to keep company with the birds and airplanes.” Austin was getting a new tallest building, though not everyone was happy about it.

In the mid-1930s, construction of the UT Tower was front page news. The Austin American-Statesman described it as “luxurious and palatial,” while the Texan waxed poetic: “Like the shining spire of some fabled city, the new Library Tower will rise in the air to keep company with the birds and airplanes.” Austin was getting a new tallest building, though not everyone was happy about it.

Make no mistake. The Texas Capitol was first in the hearts of Austin citizens. Finished in 1888, the building’s 302-foot dome was taller than the National Capitol in Washington, DC, and affirmed Austin’s role as the seat of Texas government, something the locals didn’t take for granted.

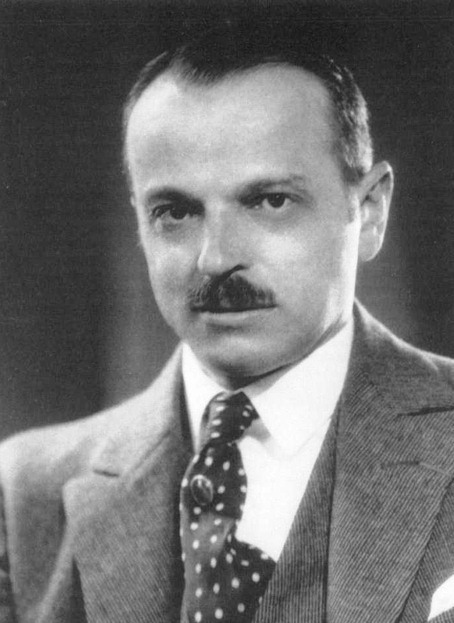

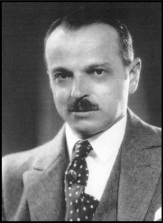

On March 8, 1930, after a decade of mixed success in campus planning, the University hired Paul Cret (image at left) as its consulting architect. A 53-year old native of France, he was a graduate of the Ecole des Beaux Arts (“School of Fine Arts”) in Paris, at the time considered the finest architecture academy in the world. Cret had immigrated to the U.S., opened a private practice in Philadelphia, and was a professor of architecture at the University of Pennsylvania.

On March 8, 1930, after a decade of mixed success in campus planning, the University hired Paul Cret (image at left) as its consulting architect. A 53-year old native of France, he was a graduate of the Ecole des Beaux Arts (“School of Fine Arts”) in Paris, at the time considered the finest architecture academy in the world. Cret had immigrated to the U.S., opened a private practice in Philadelphia, and was a professor of architecture at the University of Pennsylvania.

Cret was tasked with providing UT with a campus master plan for future development, as well as finding a solution to the University’s acute library space problem. The existing library – today’s Battle Hall – had been judged inadequate for some time. There were several proposals, among them was a new library placed either north or south of the old Main Building, or a sizable addition to the existing library. All of the plans were either too expensive or inadequate.

Above: 1926 proposed addition to the UT library. Greene, LaRoche, and Dahl of Dallas. Today’s Battle Hall is on the left, while the extension would have been to the north.

By April 3rd, less than a month into his University employment, Cret sent the Board of Regents a “Report on the Library,” and argued that the best location was on top of the hill in the middle of the Forty Acres, the site then occupied by Old Main. He explained that the library would need to be centrally located and easily accessible. Because of the space requirements for book stacks and reading rooms, it would also be the largest and most monumental structure on the campus, which required a prominent setting. To Cret, the proper location of the new library was vital, as it was quickly becoming the focus of his campus master plan.

Above: The 1933 campus master plan for the University of Texas. The Tower is the focus, from which malls extend in the four cardinal directions. (The North Mall wasn’t implemented.) UT Buildings Collection, Alexander Architectural Archives, UT Austin.

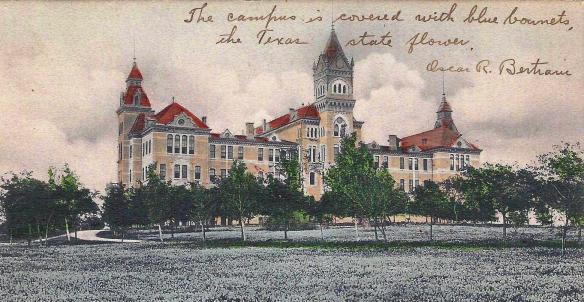

While University authorities knew that the eventual removal of Old Main was likely, they weren’t prepared for it just yet. After all, the ivy-draped, Victorian-Gothic Old Main was the first building on the campus. It had great historical and sentimental value, especially with the alumni.

To solve the library space problem, keep the desired site, reduce costs, and not offend the alumni, Cret proposed building the library in two phases. The back, lower portion of the library would be constructed first. Officially designated the “Library Annex,” it included a main desk and reading rooms, along with several floors of book stacks. (Today, the area is used by the Life Sciences Library.) The north wing of Old Main would be razed, but it housed an auditorium that had been declared unsafe by the Austin Fire Marshal in 1916 and was unused. The annex would be connected to the rest of Old Main by a hallway.

After a period of time – Cret suggested 20 years, or sometime in the 1950s – when the campus had grown used to the annex and more funds were available, Old Main could be retired. The south façade and stack tower would be finished to complete the new Main Building, which would then assume the role as UT’s central library.

As discussion continued about a proposed tower at UT, the Austin City Council moved to protect the view and importance of the Capitol. The concern was understandable. Through the 1920s, fellow Texas cities of Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio had all added near 400-foot tall skyscrapers to their skylines. Some feared that a similar development in Austin could shroud the all-important Capitol dome.

On April 23, 1931, Austin passed its first zoning plan, which limited the height of new downtown buildings to 150 feet. (It was later amended to 200 feet.) Exceptions could be granted. Two days later, on April 25th, the Board of Regents approved Cret’s two-part construction plan. Funding was granted in 1932, and the Library Annex completed the following year.

Above: Construction of the Library Annex, which included a reference desk and and two large reading rooms: The Hall of Texas and The Hall of Noble Words. The central tower of Old Main is on the right. (For more construction images, see: How to Build a Tower.) UT Buildings Collection, Alexander Architectural Archives, UT Austin.

Phase one was to quietly sit behind Old Main for the next two decades, but pressure was mounting to find a way to complete the building early. Despite the economic challenges of the Great Depression, the 1930s were boon years for the University. The discovery of oil on UT-owned West Texas land had caused the Permanent University Fund to balloon with newly-acquired oil royalties, while a special constitutional amendment allowed the University to borrow directly against the PUF and launch a multi-million dollar building program. The Texas Union, Gregory and Anna Hiss Gymnasiums, Hogg Memorial Auditorium, along with new facilities for chemistry (Welch Hall), business (Waggener), architecture (Goldsmith), geology (W. C. Hogg), physics (Painter), and home economics (Mary Gearing) were all included. All of this activity generated an abundance of construction jobs, which helped to spare Austin from the brunt of the Depression.

Wanting to continue the trend, the University hoped to go ahead and finish the library. It applied for and was granted a loan from the Progress Works Administration, one of the many New Deal programs created by President Franklin Roosevelt. The Austin City Council approved a height exemption for the 307-foot Tower, the only building to receive such an allowance for the next 30 years. Steam shovels began construction on phase two of the library in January 1935, and the completed Main Building was dedicated on February 27, 1937.

“Austin’s bid for metropolitan fame is progressing,” announced the Statesman. The University’s new Tower was not only five feet taller than the Capitol, the UT site was on a hill farther up the Colorado River valley and higher than the Capitol grounds. All told, the Tower enjoyed a 48-foot advantage in elevation.

“Austin’s bid for metropolitan fame is progressing,” announced the Statesman. The University’s new Tower was not only five feet taller than the Capitol, the UT site was on a hill farther up the Colorado River valley and higher than the Capitol grounds. All told, the Tower enjoyed a 48-foot advantage in elevation.

Most of Austin’s citizens approved of the new Tower, but not everyone. Famed author and folklorist J. Frank Dobie was pointed: “For a university that owns 2,000,000 acres of land . . . it’s ridiculous. It’s like a toothpick in a pie.”

~~~~~~~~~~

Above: Old Main floodlit on Thanksgiving Eve, 1923.

Initially, there were no plans to illuminate the Tower. After all, it wasn’t supposed to be built for another 20 years. Floodlights, though, had already been on campus for some time. In 1916, as part of a great homecoming celebration for Thanksgiving weekend, temporary lights were installed in front of the old Main Building. The south façade was brilliantly lit, and Old Main’s Gothic-arched windows and steep rooftops could be seen for miles. It was a first for Austin. The lighting effect was so popular, it became a biennial tradition.

Not to be outdone, the Texas Legislature appropriated funds to illuminate the Capitol dome. (Image at left.) In February 1925, more than 90 General Electric floodlight projectors, most of them placed on the roofs of the Capitol’s east and west wings, were aimed at the outside of the dome, while 20 amber-colored lights were placed inside to shine through the windows. Another three amber lights were located in the “tholos,” the glass-enclosed, lighthouse-like room just above the dome. The arrangement was similar to what was then being used at the National Capitol.

Not to be outdone, the Texas Legislature appropriated funds to illuminate the Capitol dome. (Image at left.) In February 1925, more than 90 General Electric floodlight projectors, most of them placed on the roofs of the Capitol’s east and west wings, were aimed at the outside of the dome, while 20 amber-colored lights were placed inside to shine through the windows. Another three amber lights were located in the “tholos,” the glass-enclosed, lighthouse-like room just above the dome. The arrangement was similar to what was then being used at the National Capitol.

The efforts to floodlight the Texas Capitol and, to a lesser extent, Old Main, were part of a much larger, national discourse between lighting engineers and architects on the use of external lighting for buildings. With origins dating back to the late 19th century – the 1889 World Exhibition in Paris featured the Eiffel Tower as a “light tower,” while the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago was famous for its vivid “White City” – the increasing use of electric lights had reinvented the nocturnal urban landscape. As skyscrapers grew ever taller in the 1910s, experiments in external lighting soon followed. By the 1920s and ‘30s, aided by a substantial drop in the price of electricity, thousands of buildings in the United States were illuminated.

Above: The 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The use of electric lights to outline the buildings and illuminate fountains had a profound influence on urban planning and the nighttime environment of cities.

Some architects considered floodlights a new building material, and proactively designed their projects to be seen after sunset. “Night illumination attracts attention like a spotlight on a stage,” claimed skyscraper architect Harvey Corbett. “The possibilities of night illumination have barely been touched,” added Raymond Hood. “There is still to be studied the whole realm of color, both in the light itself and in the quality and color of the reflecting surfaces, pattern studies in light, shade and color, and last of all, movement.” The use of floodlights seemed to accessorize what might otherwise have been dark and ominous structures. It gave them bright and cheerful nighttime garments, which transformed the American city. “There is a new Manhattan skyline – a new city of light and color rising above an old one,” reported the New York Times in 1925, which described downtown as “a huge city of illuminated castles in the air.”

Some architects considered floodlights a new building material, and proactively designed their projects to be seen after sunset. “Night illumination attracts attention like a spotlight on a stage,” claimed skyscraper architect Harvey Corbett. “The possibilities of night illumination have barely been touched,” added Raymond Hood. “There is still to be studied the whole realm of color, both in the light itself and in the quality and color of the reflecting surfaces, pattern studies in light, shade and color, and last of all, movement.” The use of floodlights seemed to accessorize what might otherwise have been dark and ominous structures. It gave them bright and cheerful nighttime garments, which transformed the American city. “There is a new Manhattan skyline – a new city of light and color rising above an old one,” reported the New York Times in 1925, which described downtown as “a huge city of illuminated castles in the air.”

Above right: An idyllic image of a 1920s skyscraper with floodlights on the upper levels, described as a “jewel in a setting.”

The lights included colors and special effects. Red, amber, green and blue filters were the standard selection, though colors could be mixed to create different hues. On some buildings, repeating dimmers allowed colors to brighten and darken and blend in an endless variety.

Naturally, General Electric, Westinghouse, and other electric companies encouraged the use of illumination, especially after the onset of the Great Depression, when the sales of electrical appliances had declined. The companies published a series of booklets that not only provided detailed engineering specifications on how to install floodlights, but included essays by noted architects on aesthetics and design. At one point, GE launch an ad campaign that claimed building illumination was a means to counter the gloom of the Great Depression.

Above: In the 1920s abd ’30s, General Electric, Westinghouse, and other electric companies produced booklets with lighting specifications and essays by prominent architects.

Above: In the 1920s, other Texas cities added illuminated high-rises to their skylines, all about 400 feet tall. From left, Dallas’ Magnolia Building with its iconic red Pegasus, Houston’s Gulf Building, and San Antonio’s Tower Life Building.

~~~~~~~~~~

In June 1934, the Board of Regents met in the President’s Office – then in Sutton Hall – to review the final plans for phase two of the Main Building, which included the south façade and Tower. Paul Cret traveled from Philadelphia to personally present the sketches and drawings, and to answer the regents’ many questions. After a lengthy discussion, the designs were enthusiastically approved. Contracts were awarded in November, and construction began the following January.

Among the plans was a recommendation by the Faculty Building Committee. Influenced by national architectural trends, knowing the impact the Main Building would have on the Austin skyline as a counterpart to the State Capitol, and in deference to the much-loved tradition of illuminating Old Main, floodlights were proposed and approved for the Tower. The decision received scant attention for more than a year, until well after construction was underway. The Texan mentioned: “An indirect lighting system accomplished through the use of flood lights at strategic points along the ascension of the tower will render it visible at night for many miles around Austin.”

~~~~~~~~~~

The person assigned to oversee the floodlight project was 34-year old Carl Eckhardt, Jr. (Image at right.) Twice a UT graduate, he earned a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering in 1925 and a master’s in 1930. Eckhardt joined the engineering faculty as an instructor in 1926, was promoted to adjunct professor when he completed his master’s degree, and was made a full professor in 1936. An avid collector of the writings of Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Byron, Browning, Thomas Paine, and others, he made it a habit to end each of his engineering classes with a tidbit of prose or poetry as a thought for the day. “In my opinion,” Eckhardt explained, “an engineer should be as cultured as anyone else, even more so.”

The person assigned to oversee the floodlight project was 34-year old Carl Eckhardt, Jr. (Image at right.) Twice a UT graduate, he earned a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering in 1925 and a master’s in 1930. Eckhardt joined the engineering faculty as an instructor in 1926, was promoted to adjunct professor when he completed his master’s degree, and was made a full professor in 1936. An avid collector of the writings of Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Byron, Browning, Thomas Paine, and others, he made it a habit to end each of his engineering classes with a tidbit of prose or poetry as a thought for the day. “In my opinion,” Eckhardt explained, “an engineer should be as cultured as anyone else, even more so.”

Along with his faculty responsibilities, Eckhardt took on several demanding roles on the Forty Acres. He was appointed Superintendent of Power Plants in 1930, and then was promoted to Superintendent of Utilities in 1936, just as he was named a full professor. In 1950, he helped to organize the physical plant department and served as its inaugural director for two decades. Eckhardt was, quite literally, in charge of the campus. His hours were legendary. Eckhardt usually arrived for work at 7 a.m., and, but for two half hour breaks for lunch and dinner, usually stayed until 10 p.m.

For anyone who has spent some time on the Forty Acres, it’s difficult not to encounter one of Eckhardt’s many contributions to the University. Starting in 1956, he originated most of the ceremonial maces used for commencement. (Image at left.) Some made from pieces of Old Main, each one is full of imagery pertaining to the schools and colleges, University leadership, and alumni.

For anyone who has spent some time on the Forty Acres, it’s difficult not to encounter one of Eckhardt’s many contributions to the University. Starting in 1956, he originated most of the ceremonial maces used for commencement. (Image at left.) Some made from pieces of Old Main, each one is full of imagery pertaining to the schools and colleges, University leadership, and alumni.

In 1958, as part of UT’s 75th anniversary celebration, Eckhardt oversaw the reconstruction of the Santa Rita oil pump on the south side of campus. Until recently, an audio recording at the pump relayed the story of the oil well and its effect on the University. Eckhardt was the voice of the narration.

He planted trees across campus, including many of the cypress along Waller Creek, advocated for an annual Service Awards program to recognize the efforts of UT’s non-teaching personnel, and self-published six booklets on University history, on topics that ranged from portraits of UT’s first 20 presidents, a volume about the University’s early years, and a booklet that explains the symbolism of each of the commencement maces. (The works are in the library, and can still be found in local used book stores.) In 1980, a then-retired Professor Eckhardt was awarded UT’s Presidential Citation. The University’s Heating and Power Complex is named for him.

~~~~~~~~~~

To start, Eckhardt’s crew reviewed all of the literature they could find on external illumination, including the booklets published by the electric companies, and especially those by General Electric. The University would use GE’s “Novalux” light projectors (image below right), similar to what had been employed at the Texas Capitol.

To start, Eckhardt’s crew reviewed all of the literature they could find on external illumination, including the booklets published by the electric companies, and especially those by General Electric. The University would use GE’s “Novalux” light projectors (image below right), similar to what had been employed at the Texas Capitol.

Along with white lights, the available colors were red, green, blue, and the popular amber. Initially, Eckhardt considered amber to highlight the upper portion of the Tower, (image at left) particularly around the Doric columns that enclosed the Tower’s belfry. Amber, though, is a yellow-orange hue. One look, and Eckhardt immediately realized that amber was too close to orange not to go ahead and use the University’s colors. Orange wasn’t a standard choice, however, and GE first proposed alternating red and amber lights to acquire an orange tint. But this meant extra lights would need to be installed, and, besides, the shade of orange wouldn’t be consistent along the surface of the building. Instead, Eckhardt ordered custom orange covers for the floodlights.

The floodlights arrived May 1937, the last significant piece of the Main Building, and were installed and individually positioned through the summer. While the building had already been dedicated on February 27th, the University wasn’t to officially occupy the space until the fall.

The floodlights arrived May 1937, the last significant piece of the Main Building, and were installed and individually positioned through the summer. While the building had already been dedicated on February 27th, the University wasn’t to officially occupy the space until the fall.

In all, 292 floodlights, half orange and half white, were placed on the four recesses, or “setbacks” of the Tower. The largest were the 96 1,000-watt lights at the Tower base, another 64 250-watt lights placed on the observation deck, 48 500-watt projectors to illuminate the belfry, and 84 100-watt bulbs around the parapet at the top. There were two circuits at each setback: one for all-orange lights, the other for all-white. Switches on the ground floor of the Main Building permitted the choice of color for each level.

~~~~~~~~~~

The evening forecast for Tuesday, October 19, 1937 was postcard worthy: clear, cool, star-filled skies with a full moon. Everything was ready. At dusk, just before 6 p.m., the Tower was officially illuminated for the first time.

The evening forecast for Tuesday, October 19, 1937 was postcard worthy: clear, cool, star-filled skies with a full moon. Everything was ready. At dusk, just before 6 p.m., the Tower was officially illuminated for the first time.

Eckhardt’s crew didn’t go for a simple, all-white or all-orange Tower. For this first attempt, they opted for something more subtle and elegant, and practical at the same time. Perhaps inspired by the images of multi-colored buildings in the floodlighting booklets, the crew wanted to try out more of the available palette, which, in this case, included a shade of light orange by combining orange and white lights together.

On the night a floodlit Tower made its debut, the lower portion remained white, while the area just above the observation deck – which included the clock faces – was bright orange. Above that, the belfry displayed a light orange tone, while bright white shown from the crown. (Image above left.) Today, the colors might be likened to an orange creamsicle.

The lights drew raves on and off campus. The following morning, Texan reporters Frank White and Bob Wilkinson called it “majestic splendor.” Their fellow students, “seeing it with us were entranced with its colorful beauty, and found no words to describe it.” The Statesman’s gossip columnist “Peeping Peggy” Harding gushed, “that the University colors of orange and white could blend so perfectly as they did that first night in the lights on the tower was a surprise to me; but the shading from bright orange at the base of the clock to white at the peak was a splendid sight. I think that experiment after experiment may be tried but none will be as effective as it was the first night.”

The experiments to which Harding referred were a seemingly endless variety of Tower lighting schemes that began October 19th and continued for nearly a year. In her column, she praised “Carl Eckhardt, supervising engineer of the beautiful doings taking place on the tower of the administration-library building on the campus. The effects gained with the various combinations that have been shown are wonderful, and at night as the hills lift their purple crown over the city, heads turn in the direction of the university to see the beauty there.”

The experiments to which Harding referred were a seemingly endless variety of Tower lighting schemes that began October 19th and continued for nearly a year. In her column, she praised “Carl Eckhardt, supervising engineer of the beautiful doings taking place on the tower of the administration-library building on the campus. The effects gained with the various combinations that have been shown are wonderful, and at night as the hills lift their purple crown over the city, heads turn in the direction of the university to see the beauty there.”

Which design (or designs) University officials favored remained a mystery. “Tonight you may see an entirely different lighting arrangement,” stated the Texan, “depending upon the mood of the experimental crew. Acceptance of the lights is pending University approval, and what you see for the next few nights is definitely not definite.”

~~~~~~~~~~

For UT football fans, the 1937 season was a long one. First-year head coach Dana Bible (image at left), recruited from the University of Nebraska to serve as both athletic director and coach, said that he would need five years to turn around what was then a lackluster football program. By the end of the season, it looked as if he might need all of it, and then some.

For UT football fans, the 1937 season was a long one. First-year head coach Dana Bible (image at left), recruited from the University of Nebraska to serve as both athletic director and coach, said that he would need five years to turn around what was then a lackluster football program. By the end of the season, it looked as if he might need all of it, and then some.

Texas opened with a win. Under cloudy skies and in front of a sparse 12,000 fans in Texas Memorial Stadium, the Longhorns scored a dozen points in the final quarter to beat Texas Tech 25–12. The undefeated streak, though, was short one. A trip to Baton Rouge, Louisiana the following week resulted in a 0-9 drubbing from LSU, and the third game of the season ended in a 7-7 tie with rival Oklahoma at the Cotton Bowl. Texas then posted three consecutive losses to Arkansas, Rice, and Southern Methodist.

Above: 1937 Texas (in white jersey and helmets – with no face guards!) vs. Baylor.

The great bright spot of the season came Saturday afternoon, November 6, in Waco, when a late field goal launched the Longhorns over the 4th-ranked Baylor Bears 9-6. Celebrations in Austin continued well into the night, especially on campus, where the weekly All-University Dance was held in the Texas Union Ballroom. Just a few steps from the Union, up the West Mall, the Tower base glowed white with the top portion bright orange. Like a giant victory flame in the middle of the Forty Acres, it reflected the jubilant mood of the University.

The great bright spot of the season came Saturday afternoon, November 6, in Waco, when a late field goal launched the Longhorns over the 4th-ranked Baylor Bears 9-6. Celebrations in Austin continued well into the night, especially on campus, where the weekly All-University Dance was held in the Texas Union Ballroom. Just a few steps from the Union, up the West Mall, the Tower base glowed white with the top portion bright orange. Like a giant victory flame in the middle of the Forty Acres, it reflected the jubilant mood of the University.

This has often been recorded as the start of the orange Tower tradition. While it’s true that the Tower was floodlit orange on the night of a Longhorn win, the former didn’t yet depend on the latter. Floodlights had been used for less than three weeks. No guidelines had been set, even the idea to use the orange lights in such a way hadn’t yet occurred to the lighting crew. The Tower was already set-up and scheduled to shine as it did, regardless of the final score in Waco. As Eckhardt later explained, “At the time we attached no importance to it. Like so many things that have become traditions, it only became important later.”

Above right: From 1938, one of the earliest color photographs of the Tower and Texas Union on the West Mall.

The campus was jazzed all week after the Baylor game. Was it a fluke, or had the Longhorns turned a corner? With Texas Christian University coming to Austin the next weekend, a Friday night football rally was scheduled on the newly-paved Main Mall, which hadn’t yet been landscaped with hedges and oak trees. On the morning of the rally, the Texan reported, “Even the University administration has gotten into the spirit of things. Bright orange lights, at special expense, will be diffused around the Tower tonight.”

The campus was jazzed all week after the Baylor game. Was it a fluke, or had the Longhorns turned a corner? With Texas Christian University coming to Austin the next weekend, a Friday night football rally was scheduled on the newly-paved Main Mall, which hadn’t yet been landscaped with hedges and oak trees. On the morning of the rally, the Texan reported, “Even the University administration has gotten into the spirit of things. Bright orange lights, at special expense, will be diffused around the Tower tonight.”

Just after 7 p.m. Friday evening, a torchlight parade led by the Longhorn Band set out from the front of the Scottish Rite Dorm, marched down Guadalupe, turned east on 21st Street, and then up the South Mall to the Tower, which was floodlit in the same way it appeared the previous Saturday, with the top portion orange. (Image upper left.)

Above: A crowd gathers on the Main Mall for the Beat TCU football rally. The familiar hedges and oak tress haven’t yet been planted. Below, Bevo III at the rally.

More than 2,000 fans, Coach Bible, the football team, Austin Mayor Tom Miller, and Bevo III (image at right) made it the largest and loudest rally of the season. Unfortunately, Texas went scoreless on Saturday while TCU prevailed 0-14. The next week in College Station, Texas A&M beat the Longhorns 0-7, and the soon-to-be-forgotten 1937 season ended at 2-6-1.

More than 2,000 fans, Coach Bible, the football team, Austin Mayor Tom Miller, and Bevo III (image at right) made it the largest and loudest rally of the season. Unfortunately, Texas went scoreless on Saturday while TCU prevailed 0-14. The next week in College Station, Texas A&M beat the Longhorns 0-7, and the soon-to-be-forgotten 1937 season ended at 2-6-1.

Still, the win over Baylor and the TCU rally planted an idea with Eckhardt: what if the orange floodlights, instead of being used every night as part of a standard lighting scheme, were instead reserved for special occasions?

~~~~~~~~~~

The Tower light show continued into 1938 and was gaining a fan base both inside and out of the Austin city limits. “When lighted at night, the Tower can be seen in Round Rock, Manor, and other surrounding towns,” reported the Statesman. “Persons at San Marcos say it can be seen from the hills around San Marcos.” The best view was from the south, when entering Austin along present-day South Congress Avenue. “From the crest of the hill (today’s South Congress at Ben White Boulevard), the lighted Tower behind the lighted dome of the Texas Capitol offers a breath-taking sight.”

The Tower light show continued into 1938 and was gaining a fan base both inside and out of the Austin city limits. “When lighted at night, the Tower can be seen in Round Rock, Manor, and other surrounding towns,” reported the Statesman. “Persons at San Marcos say it can be seen from the hills around San Marcos.” The best view was from the south, when entering Austin along present-day South Congress Avenue. “From the crest of the hill (today’s South Congress at Ben White Boulevard), the lighted Tower behind the lighted dome of the Texas Capitol offers a breath-taking sight.”

University officials boasted that, just by changing a single bulb, there were an estimated 60,000 possible lighting schemes. Among them, as the Texan described, “Some nights the main body of the Tower is white with a faint orange tinge. Solid white light plays on the clocks and deep orange lights on the area above.” (Image above right.)

At other times, the lower part of the Tower was left dark, with only the upper portion lit up in some combination of oranges and white. From a distance, the effect made it seem as if the illuminated clock and belfry were disconnected from the rest of the Main Building, suspended over the campus. More than a few students voiced their support for the idea. Journalism major and track team sprinter Hiram Reeves said, “I don’t like the whole Tower flooded with light. The two sections at the top are enough. The first one should be orange and the next white.” Anida Derst chimed in, “Isn’t it beautiful? I think only the top should be lighted. I like orange and then white.” Mary Lou Humlong (image upper left) agreed with order of colors, but wanted to go bigger: “I would like to see them flood the complete lower part of the Tower with orange, and use white only at the very top.” The use of white lights on the upper portion also highlighted the extensive gold leaf that was originally placed around the clock and the belfry. (See: The Tower Gold Rush.)

At other times, the lower part of the Tower was left dark, with only the upper portion lit up in some combination of oranges and white. From a distance, the effect made it seem as if the illuminated clock and belfry were disconnected from the rest of the Main Building, suspended over the campus. More than a few students voiced their support for the idea. Journalism major and track team sprinter Hiram Reeves said, “I don’t like the whole Tower flooded with light. The two sections at the top are enough. The first one should be orange and the next white.” Anida Derst chimed in, “Isn’t it beautiful? I think only the top should be lighted. I like orange and then white.” Mary Lou Humlong (image upper left) agreed with order of colors, but wanted to go bigger: “I would like to see them flood the complete lower part of the Tower with orange, and use white only at the very top.” The use of white lights on the upper portion also highlighted the extensive gold leaf that was originally placed around the clock and the belfry. (See: The Tower Gold Rush.)

At one point, the lighting crew attempted a striped Tower, with a center white stripe and orange along the sides. Students, though, claimed it reminded them of a barber pole, and joked that the University was advertising itself as a barber college. The stripes didn’t work all that well anyway, as the lights diffused and blended with height, which blurred the vertical lines. Alternating each of the four sides of the Tower in orange and white was also tried.

Above: Some of the early Tower lighting experiments. From left: the “creamsicle” Tower seen on the first night, the top-lit only Tower, a vertically striped Tower, and a horizontally striped Tower with alternating orange and white levels..

As winter warmed into spring, and on into summer, the Tower lights continued to entertain, but were more often seen in four basic configurations: all-white, with an orange base and white top (as Mary Lou Humlong preferred), with a white base and orange top, and all-orange. While light orange was popular and still made an occasional appearance, the use of both orange and white lights on the same setback made that section a little brighter than the rest and created an uneven composition.

Above: The four basic lighting patterns that began to appear in the summer of 1938.

At the same time, the crew determined that lighting the upper portion of the Tower more than one color was difficult to see from greater distances. For example, the four levels of the Tower could be lit – and was, as one of the experiments – alternately white and orange from bottom to top, with an orange crown. (Image at left.) On campus and nearby, the design was easy enough to see, but from two miles away and farther, the details were harder to discern. Eckhardt determined it was best to light the entire upper portion of the Tower a single color.

At the same time, the crew determined that lighting the upper portion of the Tower more than one color was difficult to see from greater distances. For example, the four levels of the Tower could be lit – and was, as one of the experiments – alternately white and orange from bottom to top, with an orange crown. (Image at left.) On campus and nearby, the design was easy enough to see, but from two miles away and farther, the details were harder to discern. Eckhardt determined it was best to light the entire upper portion of the Tower a single color.

As the fall semester opened, an all-white Tower was more often seen. Eckhardt began to use the orange lights sparingly, as reported by the Statesman, “confined to those times when the campus is visited by out-of-town and out-of-state groups, or when the university sponsors some annual event.” This included the June 1938 commencement ceremonies, held for the first time on the Main Mall, when the top portion of the Tower glowed orange to honor the graduates.

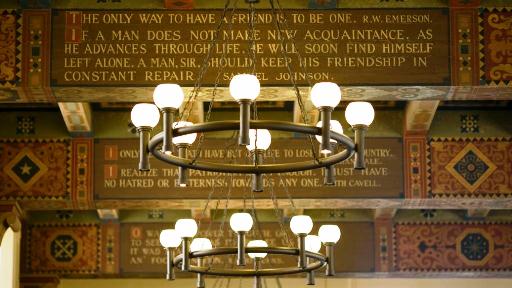

While the lighting experiments had slowed, there was still no set policy on the use of the Tower floodlights. Why so long to make a decision? At the time, the University was without a formal president. The much-loved Harry Benedict, who‘d served as UT’s chief executive for a decade, died unexpectedly in May 1937. The Board of Regents appointed John Calhoun, a math professor and the University’s comptroller, as president ad interim. Calhoun was a longtime and influential member of the Faculty Building Committee and had suggested the inscription that was carved on the front of the Main Building (See: The Inscription), but opted to leave the final decision on the Tower lighting to his successor.

~~~~~~~~~~

Above: Coach Bible at a Longhorn football practice.

If the 1937 football season was bad, 1938 was worse.

At the start, the Longhorns suffered a frustrating, one-point, 18-19 defeat at the University of Kansas. LSU came to Austin the following week. The Tigers picked up where they left off the previous year, and handed Texas a second, 0-20 drubbing. Oklahoma was next on the schedule.

On Tuesday morning, October 4th, a few days before the showdown with the Sooners, the Statesman printed its popular and chatty “Town Talk” column by Editor-in-chief Charles Green.

“They’ve been having such a good time out at the University of Texas with the tower on the administration building that it seems a shame to say anything” wrote Green. “But why not have a little meaning in the change of the lights of the building – at least during football season? How would it be to flash on the orange lights and white lights when Texas had been victorious so that everyone would see and know and each night see and know again? And, on the other hand, when Texas goes down in defeat, light the tower in the calm white light? So that football players, as well as others, would see it every night and remember just what it meant.”

“They’ve been having such a good time out at the University of Texas with the tower on the administration building that it seems a shame to say anything” wrote Green. “But why not have a little meaning in the change of the lights of the building – at least during football season? How would it be to flash on the orange lights and white lights when Texas had been victorious so that everyone would see and know and each night see and know again? And, on the other hand, when Texas goes down in defeat, light the tower in the calm white light? So that football players, as well as others, would see it every night and remember just what it meant.”

“Well, it’s just an idea,” Green continued. Maybe it’d be an inspiration. But any way you take it, that tower agleam with light is something to look at.”

The Texan responded. “One of the good ideas “Town Talk” in a downtown paper developed the other day was a new lighting system for the Tower. The plan called for lighting the Library shaft with the orange and white lights the following week if Texas won the football game and using solid white ones if we lost. The lighting effect would remind players as well as other students of the game the previous week and might help get them in the mood to keep the lights from being all white.”

While the time periods were different – Green proposed using orange lights only for the night of the football game, while the Texan had orange lights on the Tower for a week – the basic idea was the same. It fit perfectly with Eckhardt’s notions for making the orange lights special, and he welcomed the suggestion.

The “victory lights,” though, would have to wait a while. Texas was blanked by Oklahoma 0-13, and the Longhorns followed it up with losses to Arkansas, Rice, SMU, Baylor, and eventual national champion TCU. Only one game remained. The lone chance to redeem the season was the Thanksgiving Day bout with Texas A&M in Austin.

The “victory lights,” though, would have to wait a while. Texas was blanked by Oklahoma 0-13, and the Longhorns followed it up with losses to Arkansas, Rice, SMU, Baylor, and eventual national champion TCU. Only one game remained. The lone chance to redeem the season was the Thanksgiving Day bout with Texas A&M in Austin.

As had been the custom when the game was played at UT, alumni turned it into an unofficial homecoming and invaded Austin in droves. This was also the first home game versus the Aggies when the Main Building and Tower were fully operational. In the spirit of the prior tradition of floodlighting Old Main, Eckhardt ordered a distinctive all-orange Tower for the alumni the nights before and of Thanksgiving. (Image upper left.)

Wednesday night’s Thanksgiving Eve began with a football rally of 4,000 in front of Gregory Gym, followed by a second, bonfire rally on present-day Clark Field, and then a march en masse to Sixth Street downtown. Thanksgiving Day was a holiday for most, but much of UT held an open house in the morning to accommodate the surge of visitors. The president’s and deans’ offices, library in the Main Building, Tower observation deck, and campus museums were all available until 1 p.m. The Texas Union, then headquarters for the alumni association, was open all day. Kick-off for the game was at 2:30 p.m., and the University-wide Thanksgiving Dance was set for Gregory Gym that night.

Wednesday night’s Thanksgiving Eve began with a football rally of 4,000 in front of Gregory Gym, followed by a second, bonfire rally on present-day Clark Field, and then a march en masse to Sixth Street downtown. Thanksgiving Day was a holiday for most, but much of UT held an open house in the morning to accommodate the surge of visitors. The president’s and deans’ offices, library in the Main Building, Tower observation deck, and campus museums were all available until 1 p.m. The Texas Union, then headquarters for the alumni association, was open all day. Kick-off for the game was at 2:30 p.m., and the University-wide Thanksgiving Dance was set for Gregory Gym that night.

More than 35,000 fans packed the stadium as an inspired Longhorn defense kept the game scoreless for three quarters. Early in the fourth, halfback Nelson Puett made a dramatic dive over the goal line to give Texas a touchdown, and while UT hadn’t converted an extra point all season, Wally Lawson found his mark to give the Longhorns a 7-0 lead. The win seemed assured until, with less than 20 seconds left, a botched Longhorn play meant to run out the clock resulted in a fumble that was recovered by the Aggies in the end zone for a score. Texas, however, managed to block the extra point as time – and the season – ran out, leaving the final tally 7-6. Jubilant fans rushed the field.

Above: The Longhorn’s winning touchdown to beat the Aggies.

As had happened the year before with the upset over Baylor, campus reveling continued well into the night, though this time centered at the Thanksgiving Dance in Gregory Gym. An all-orange Tower presided over the Forty Acres, and while it would have been orange regardless of the score, by now, too many people connected the floodlights with the football win. What Green had suggested in the Statesman, combined with Eckhardt’s own thoughts on the use of the orange lights, as well as the lighting crew’s year-long experiment on how best to light the Tower, had all matured into a new University tradition.

And this time, the UT football program had truly turned a corner. The following 1939 season would be a winning one. Newly-appointed President Homer Rainey formally approved the idea of victory lights (with an all-orange Tower reserved for wins against A&M), and left the use of orange lights for other occasions at Eckhardt’s discretion.

And this time, the UT football program had truly turned a corner. The following 1939 season would be a winning one. Newly-appointed President Homer Rainey formally approved the idea of victory lights (with an all-orange Tower reserved for wins against A&M), and left the use of orange lights for other occasions at Eckhardt’s discretion.

Which made Eckhardt a very popular person.

Above: From the 1941 Cactus. In a recap of each game of the 1940 season, an image of a white or orange-topped Tower signified wins and losses.

~~~~~~~~~~

“Dear Professor Eckhardt, Would you please light the Tower orange for . . .”

Over the next several years, the Tower victory lights for football, spring commencement, and a few other dates became a well-established tradition, and seemed to have everyone’s attention. “If anything is wrong after some football game or some other event,” Eckhardt explained, “I get as many as two or three hundred calls at home.” There was, though, still no formal schedule for the lights, and Eckhardt constantly fielded requests, or, as he described it, “a great host of individuals who possessed a wide variety of reasons for wanting to call attention to a function in which they were participating.” Among the functions were alumni meetings and retirement parties, academic conferences hosted in Austin, fraternity formals, milestone birthdays, and championships won in sports other than football. Occasionally, Eckhardt acquiesced (always, of course, if the request was made by the president), but most were politely refused. Orange lights on the Tower were supposed to be rare and distinctive.

In 1941, soon after the U.S. entered the Second World War, Austin was deemed too close to the Gulf coast and within range of enemy bombers. An air raid siren was installed on the top of the Tower, and the city formally placed on a nighttime blackout. From January 25, 1942 to November 1, 1943 – about 19 months – both the Capitol dome and Tower were dark, though the Tower was allowed to shine for spring commencements and a Thanksgiving Day victory over Texas A&M.

In 1941, soon after the U.S. entered the Second World War, Austin was deemed too close to the Gulf coast and within range of enemy bombers. An air raid siren was installed on the top of the Tower, and the city formally placed on a nighttime blackout. From January 25, 1942 to November 1, 1943 – about 19 months – both the Capitol dome and Tower were dark, though the Tower was allowed to shine for spring commencements and a Thanksgiving Day victory over Texas A&M.

Image at right: Cover of the September 1943 Texas Ranger student magazine. A UT freshman during wartime is portrayed as a paratrooper, landing on the Forty Acres next to a dark Tower under blackout.

When the blackout was lifted, student Mary Brickerhoff (image below left) cheered via the Texan. “The Tower isn’t a building. You thought it was? That’s natural, but the building part is only an optical illusion . . . The Tower is Texas, symbolically speaking, and it is at its most impressive and its most Texan when it is lighted up at night.”

“That tall column of stone,” Brickerhoff continued, “silhouetted against a blue-black night sky and looking as though it were lighted from inside transparent walls instead of from the outside, has been affecting many very different people in the same way for a long time. In our mind’s eye – or in what we have left of it after four years of study – we can see the Tower from a dormitory window on a night of our first year here. It was several blocks away then, and it looked big and impressive. But it wasn’t unfamiliar. Something about it said, “Don’t be scared. You’ll have both fun and trouble in this place, and when it’s all over you won’t want to go back and change anything. And the Forty Acres will mean more to you than anywhere you’ve ever been.”

“That tall column of stone,” Brickerhoff continued, “silhouetted against a blue-black night sky and looking as though it were lighted from inside transparent walls instead of from the outside, has been affecting many very different people in the same way for a long time. In our mind’s eye – or in what we have left of it after four years of study – we can see the Tower from a dormitory window on a night of our first year here. It was several blocks away then, and it looked big and impressive. But it wasn’t unfamiliar. Something about it said, “Don’t be scared. You’ll have both fun and trouble in this place, and when it’s all over you won’t want to go back and change anything. And the Forty Acres will mean more to you than anywhere you’ve ever been.”

Brickerhoff expressed what many of her fellow students felt – and what future generations of UT students would feel – about the Tower, especially freshmen, who were both on their own for the first time and adjusting to college life. During the day, the Tower could be seen (and heard) from almost any spot on campus, but at night, standing proudly under a starry sky or buffeted by a Texas thunderstorm, the illuminated Tower was an image of stability and purpose in an otherwise hectic college student’s life. Had the decision been made not to use floodlights, to leave the building dark after sunset, the Tower would still have been the iconic campus landmark, but wouldn’t have engendered the same kind of passion Mary Brickerhoff described.

Above: A 1940 postcard image of the UT Tower at night.

~~~~~~~~~~

After years of endless special requests, Eckhardt at last decided that a formal lighting schedule was needed. Late in 1946, with the president’s approval, a seven-member committee discussed the issue at length, and announced their guidelines in October 1947.

The victory lights – with the top portion of the Tower orange – were to be lit on nights when the football team won, or when the men’s baseball, basketball, track, swimming, golf, and tennis teams secured a Southwest Conference championship. The lights would also be used for spring commencement and various holidays: Easter, Christmas, Texas Independence Day (March 2), San Jacinto Day (April 21), Victory in Europe Day (May 8), Victory in Japan Day (August 14), and Armistice Day (November 11). As the Second World War had ended only recently, and the University campus was crowded with veterans who’d enrolled through the G.I. Bill (See: Life in Cliff Courts), the last three holidays were still widely observed.

The victory lights – with the top portion of the Tower orange – were to be lit on nights when the football team won, or when the men’s baseball, basketball, track, swimming, golf, and tennis teams secured a Southwest Conference championship. The lights would also be used for spring commencement and various holidays: Easter, Christmas, Texas Independence Day (March 2), San Jacinto Day (April 21), Victory in Europe Day (May 8), Victory in Japan Day (August 14), and Armistice Day (November 11). As the Second World War had ended only recently, and the University campus was crowded with veterans who’d enrolled through the G.I. Bill (See: Life in Cliff Courts), the last three holidays were still widely observed.

An all-orange Tower was to be a rare sight indeed, seen only on Thanksgiving nights when the Longhorns defeated the Aggies. A great many students, though, were out-of-town for the holidays and missed out on the view. After a decade of complaints, the policy was amended in 1957 to include both Thanksgiving night and the following Sunday evening to greet returning students.

Above: The 1952 flashcard section flipped from a daytime to a nighttime orange-topped Tower, with the moon in the upper left corner. Courtesy Bob and Lou Harris.

As the years passed, the lighting schedule continued to evolve. The World War II-related holidays were eventually replaced with Memorial and Veterans’ Days. It was also quite obvious to everyone that the victory lights were reserved only for men’s sports. In 1952, Jaclyn Keasler, president of UT’s Cap and Gown, a senior women’s organization, wrote to Eckhardt about the possibility of using the lights for Swing Out. An annual spring event since 1922, part of the program involved transferring a long bluebonnet chain from the shoulders of the graduating seniors to the juniors, symbolic of passing the campus leadership roles and traditions on to the succeeding class. Eckhardt was receptive to the idea and brought it to the committee, which agreed. On May 1, 1953, the top of the Tower finally glowed orange for a women-only activity. Almost 20 years later, with the passage of Title IX in 1971 and the creation of the Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) in 1972, the University began to sponsor competitive women’s sports. By 1976, the victory lights were shining for their achievements as well.

Above: 1923 Swing Out and Bluebonnet Chain ceremony on what today is the South Mall.

On Thanksgiving night 1962, Longhorn fans were in for a surprise. The football team had not only defeated Texas A&M, but had completed its first no-loss record in over 40 years. If not for a mid-season, 14-14 tie game with Rice when Texas was ranked number one, UT would have earned the national championship. In honor of the team’s success, and in the spirit of the lighting experiments of the 1930s, Eckhardt ordered an all-orange Tower and had his crew spell out “UT” in the windows, the first time the windows were a part of the display.

On Thanksgiving night 1962, Longhorn fans were in for a surprise. The football team had not only defeated Texas A&M, but had completed its first no-loss record in over 40 years. If not for a mid-season, 14-14 tie game with Rice when Texas was ranked number one, UT would have earned the national championship. In honor of the team’s success, and in the spirit of the lighting experiments of the 1930s, Eckhardt ordered an all-orange Tower and had his crew spell out “UT” in the windows, the first time the windows were a part of the display.

The next year, the football team finished the 1963 season undefeated and ranked first, then soundly defeated number 2-ranked Navy in the Cotton Bowl on New Year’s Day to clinch the University’s first national football championship. To celebrate, the Tower was orange for three nights, from January 1 – 3, 1964, with a “1” lit in the windows on each side. To prepare, Eckhardt’s crew spent two days sealing more than 100 windows with sheets of black plastic, and then left reminders in the appropriate offices to leave their lights on for the night. Today, a specially designed pull-down shade makes the process quicker and easier.

On February 27, 2012, the Tower turned 75 years old. Students distributed birthday cake on the West Mall, the Alexander Architectural Archives, housed on the ground floor of Battle Hall, sponsored an open house with some of Paul Cret’s Tower sketches and drawings on display, and a historical tour of the Main Building was conducted in the early evening. Thanks to special approval by UT President Bill Powers, the Tower glowed orange that night with a “75” in the windows – the first time the Tower was lit orange to celebrate itself!

Above: The 2019 Spring Commencement was the 25th year fireworks were launched from the Tower. The pandemic interrupted the 2020 ceremony, though the Tower still sported a “20” in its windows. Photos by Marsha Miller.

By the 21st century, the Tower lights were thoroughly enmeshed in the University’s culture. Today, the Tower shines orange to recognize academic pursuits, including Honor’s Day, as well as faculty, staff, and alumni awards. The Tower lights not only mark the achievements of UT’s athletic teams, but national titles earned by the sports clubs under the Division of Recreational Sports. At times, the Tower is darkened in memoriam for members of the University community who have passed.

Best known, perhaps, is the use of the Tower for Spring Commencement, the signature event of the academic year. Held on the Main Mall since 1938, it was a somewhat staid ceremony with average attendance. In 1995, UT President Bob Berdahl asked that commencement be reinvented with more pomp and excitement. Special lighting effects were added to illuminate the Tower the designated color of each school and college, and the graduation year was lit in the windows. The most significant change was the addition of fireworks at the end of the ceremony. In just a few years, Spring Commencement was attracting overflow crowds of more than 20,000 persons.

The Tower lights, added almost as an afterthought to a building that was constructed 20 years early, has matured well beyond its “majestic splendor” and become a vital part of the University’s identity.

- Sources: William J. Battle Papers, Carl Eckhardt Papers, and the UT President’s Office Papers in the University Archives, preserved at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History; Robert Leon White Papers in the Alexander Architectural Archives; UT Board of Regents minutes; Architecture of the Night by Dietrich Neuman; various booklets on floodlighting published by General Electric and Westinghouse in the 1920s and ’30s. The Daily Texan and Austin American-Statesman newspapers; Texas Ranger and Alcalde magazines.

- Special thanks to the Austin History Center for helping to determine the height and site elevations of the Texas Capitol and UT Tower.

Have you heard? The main library at Indiana University is sinking into the ground at the rate of an inch a year. The fault lies with the building’s designer – a graduate from rival Purdue – as he didn’t take into account the extra weight of the books on the shelves. At Iowa State University, any student who carelessly steps on the bronze zodiac inlaid on the floor of the student union building is thereby “cursed” to flunk their next exam. Undergraduates at Princeton warily avoid exiting through the Fitz Randolph Gate at the campus entrance before they graduate. Otherwise, they may never complete their degrees. And at Columbia University in New York, the famous statue of Alma Mater has an owl hidden within the gatherings of her robes. Incoming freshman are told that the first person to find the owl will become the class valedictorian.

Have you heard? The main library at Indiana University is sinking into the ground at the rate of an inch a year. The fault lies with the building’s designer – a graduate from rival Purdue – as he didn’t take into account the extra weight of the books on the shelves. At Iowa State University, any student who carelessly steps on the bronze zodiac inlaid on the floor of the student union building is thereby “cursed” to flunk their next exam. Undergraduates at Princeton warily avoid exiting through the Fitz Randolph Gate at the campus entrance before they graduate. Otherwise, they may never complete their degrees. And at Columbia University in New York, the famous statue of Alma Mater has an owl hidden within the gatherings of her robes. Incoming freshman are told that the first person to find the owl will become the class valedictorian. Actually, the architect of UT’s Main Building and Tower was Paul Cret, who was born in Lyon, France in 1876 and graduated from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, then considered the finest place in the world to study architecture. When he was hired as consulting architect by the University in 1930, the 44-year old Cret had immigrated to the United States, was a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, and had his own private practice with offices in downtown Philadelphia.

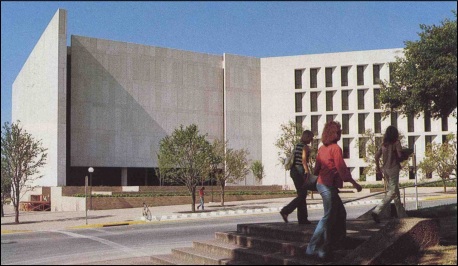

Actually, the architect of UT’s Main Building and Tower was Paul Cret, who was born in Lyon, France in 1876 and graduated from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, then considered the finest place in the world to study architecture. When he was hired as consulting architect by the University in 1930, the 44-year old Cret had immigrated to the United States, was a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, and had his own private practice with offices in downtown Philadelphia. Myth: The Perry-Castaneda Library was designed in the shape of Texas.

Myth: The Perry-Castaneda Library was designed in the shape of Texas.  University librarians were fielding questions about the shape of the Perry-Castaneda Library well before it opened in 1977. The PCL – informally known as the “PiCkLe” – was planned by the San Antonio architecture firm Bartlett, Cocke and Associates, Inc. and proactively designed to ease the pedestrian traffic around it. Instead of a traditional square or rectangular footprint, corners were trimmed to allow for diagonal pathways in front and behind the building. Other parts were extended to make the best use of available area. The end result was actually meant to better resemble a pinwheel, not the Lone Star State. The Board of Regents approved the plans in March 1974, along with $17 million for construction. (For more about the PCL, see: Forty Years on Forty Acres.)

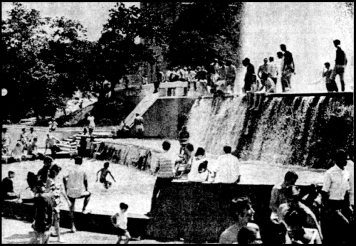

University librarians were fielding questions about the shape of the Perry-Castaneda Library well before it opened in 1977. The PCL – informally known as the “PiCkLe” – was planned by the San Antonio architecture firm Bartlett, Cocke and Associates, Inc. and proactively designed to ease the pedestrian traffic around it. Instead of a traditional square or rectangular footprint, corners were trimmed to allow for diagonal pathways in front and behind the building. Other parts were extended to make the best use of available area. The end result was actually meant to better resemble a pinwheel, not the Lone Star State. The Board of Regents approved the plans in March 1974, along with $17 million for construction. (For more about the PCL, see: Forty Years on Forty Acres.) At 2 p.m. on the sunny afternoon of August 3, 1969, several hundred “hippies, would-be hippies, and clean-cut American kids” gathered at the fountain. Organized by the Student Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, a brief ceremony dubbed the structure “Peace Fountain” before the group took full advantage of the cooling waters on a hot summer day. The event was reported in both The Daily Texan and The Austin American.

At 2 p.m. on the sunny afternoon of August 3, 1969, several hundred “hippies, would-be hippies, and clean-cut American kids” gathered at the fountain. Organized by the Student Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, a brief ceremony dubbed the structure “Peace Fountain” before the group took full advantage of the cooling waters on a hot summer day. The event was reported in both The Daily Texan and The Austin American. Certainly, the window pattern on Burdine is unusual, and this kind of thing is ripe for a campus myth, but it’s not true. Burdine Hall was opened in May 1970 for the departments of Government and Sociology. It’s named for John Alton Burdine, a longtime government professor who also served as dean of the College of Arts and Sciences (which has since been separated into several colleges and schools).

Certainly, the window pattern on Burdine is unusual, and this kind of thing is ripe for a campus myth, but it’s not true. Burdine Hall was opened in May 1970 for the departments of Government and Sociology. It’s named for John Alton Burdine, a longtime government professor who also served as dean of the College of Arts and Sciences (which has since been separated into several colleges and schools). A native of North Carolina, Battle was a newly-minted Harvard Ph.D. when he joined the UT faculty in 1893. A professor of Greek and classical studies, he quickly rose through the academic ranks, served as Dean of the University (today called the Provost), and was appointed President ad interim. Along the way, Battle founded the University Co-op through a $2,300 personal loan (his annual salary was $2,500), compiled the first campus directory, and designed the University Seal.

A native of North Carolina, Battle was a newly-minted Harvard Ph.D. when he joined the UT faculty in 1893. A professor of Greek and classical studies, he quickly rose through the academic ranks, served as Dean of the University (today called the Provost), and was appointed President ad interim. Along the way, Battle founded the University Co-op through a $2,300 personal loan (his annual salary was $2,500), compiled the first campus directory, and designed the University Seal. A decade ago, there were six additional statues along the South Mall as part of the Littlefield Gateway, and four of them were of persons with direct ties to the Confederacy. It’s understandable that a visitor back then might think the likeness of Washington was connected to the same undertaking. It was centrally positioned, surrounded by the other statues, and was sculpted by the same artist. A closer inspection of the dates and inscriptions, though, shows the Washington statue was a separate project with a very different intent.

A decade ago, there were six additional statues along the South Mall as part of the Littlefield Gateway, and four of them were of persons with direct ties to the Confederacy. It’s understandable that a visitor back then might think the likeness of Washington was connected to the same undertaking. It was centrally positioned, surrounded by the other statues, and was sculpted by the same artist. A closer inspection of the dates and inscriptions, though, shows the Washington statue was a separate project with a very different intent. The intent was to have a statue installed by the Washington bicentennial in February 1932, but the Great Depression made fundraising difficult, as well as the Second World War that followed. (The same affected construction of the North Mall as discussed above.) Not until the 1950s was fundraising completed and artist Pompeo Coppini, who’d sculpted the Littlefield Fountain and other South Mall statues, secured for the project. The statue was dedicated in 1955.

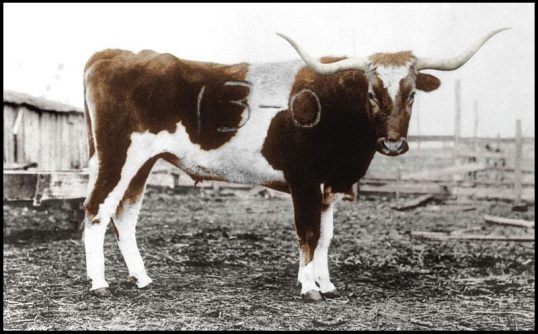

The intent was to have a statue installed by the Washington bicentennial in February 1932, but the Great Depression made fundraising difficult, as well as the Second World War that followed. (The same affected construction of the North Mall as discussed above.) Not until the 1950s was fundraising completed and artist Pompeo Coppini, who’d sculpted the Littlefield Fountain and other South Mall statues, secured for the project. The statue was dedicated in 1955. Aggie fans, though, went on to assert that, in order to save face, UT students altered the brand. The “13” was changed into a “B,” the dash into an “E,” a “V” inserted before the “0,” and thus was born the name “Bevo.” This is a myth.

Aggie fans, though, went on to assert that, in order to save face, UT students altered the brand. The “13” was changed into a “B,” the dash into an “E,” a “V” inserted before the “0,” and thus was born the name “Bevo.” This is a myth.

For anyone who has spent some time on the Forty Acres, it’s difficult not to encounter one of Eckhardt’s many contributions to the University. Starting in 1956, he originated most of the ceremonial maces used for commencement. (Image at left.) Some made from pieces of Old Main, each one is full of imagery pertaining to the schools and colleges, University leadership, and alumni.

For anyone who has spent some time on the Forty Acres, it’s difficult not to encounter one of Eckhardt’s many contributions to the University. Starting in 1956, he originated most of the ceremonial maces used for commencement. (Image at left.) Some made from pieces of Old Main, each one is full of imagery pertaining to the schools and colleges, University leadership, and alumni.

The victory lights – with the top portion of the Tower orange – were to be lit on nights when the football team won, or when the men’s baseball, basketball, track, swimming, golf, and tennis teams secured a Southwest Conference championship. The lights would also be used for spring commencement and various holidays: Easter, Christmas, Texas Independence Day (March 2), San Jacinto Day (April 21), Victory in Europe Day (May 8), Victory in Japan Day (August 14), and Armistice Day (November 11). As the Second World War had ended only recently, and the University campus was crowded with veterans who’d enrolled through the G.I. Bill (See:

The victory lights – with the top portion of the Tower orange – were to be lit on nights when the football team won, or when the men’s baseball, basketball, track, swimming, golf, and tennis teams secured a Southwest Conference championship. The lights would also be used for spring commencement and various holidays: Easter, Christmas, Texas Independence Day (March 2), San Jacinto Day (April 21), Victory in Europe Day (May 8), Victory in Japan Day (August 14), and Armistice Day (November 11). As the Second World War had ended only recently, and the University campus was crowded with veterans who’d enrolled through the G.I. Bill (See: