EVENTS

2.

Mary, the Republic, and the Basques

During July and August 1931 at Ezkioga in northern Spain, scores of Basque seers had increasingly elaborate and explicit visions of the Virgin. The visions offered a way to mobilize the Basque community and focus their hopes. Watching Basque society define and tap this new power is like watching a kind of social x-ray or scanner. In the case of the Ezkioga visions, the scan highlights a struggle between competing views of the world. At a turning point in Basque and Spanish history, local leaders, the press, and the audience helped the visionaries to articulate general concerns.

The Republic and the Catholic North

From 1874 to 1923 Spain was a constitutional monarchy in which the Liberal and Conservative oligarchic parties alternated in power. During this period parts of Catalonia and the Basque Country rapidly industrialized. As in much of Western Europe and North America, the labor movement in Spain reached a peak of strength at the conclusion of World War I. In the face

of labor unrest and regionalist movements, General Miguel Primo de Rivera installed a military dictatorship, still under royal legitimacy, which lasted from 1923 to 1930. After the general stepped down, the municipal elections of April 1931 became a referendum on the monarchy itself. Republicans won in most major cities and proclaimed the Second Republic. King Alfonso XIII went into exile.

The fall of the monarchy jarred an entire order in which for centuries the relation of king to subjects had been the model for relations of God to persons. By extension it even shook the belief in God. It opened the door to changes in relations between women and men, workers and employers, laity and priests, and children and parents. Human relations are by nature imitative. The change to a republic led to changes in the ways people treated one another. Of course, the fall of the monarchy was effect as well as cause—the effect of gradual shifts in a whole host of social relations, particularly as a result of militant labor movements. Visions of Mary throughout Spain in the spring and summer of 1931 were short-term consequences of the change in the regime, but they also reflected more long-term changes.

On 23 April 1931, nine days after the advent of the Republic, children playing outside the church of Torralba de Aragón (Huesca) saw what they thought was the figure of the Virgin Mary pacing inside, and one girl heard the Virgin say, "Do not mistreat my son." Citizens took this to be a reference to a crucifix in the town hall which the anarchist minority had taken down and broken up. Catholic newspapers reported this vision throughout Spain.[1]

Two weeks later, from May 11 to 13, anticlerical vandals set fire to dozens of religious houses in Madrid and Andalusia. Banner headlines and photographs of gutted buildings and headless images left Spain's Catholics with little doubt about the will of the new republic to defend church property. In mid-May seminary professors in Vitoria, seat of the Basque diocese, concluded that they had no way to affect the policies of the government in Madrid and that instead they should concentrate on preserving the faith in the Basque Country. A priest who attended the gathering told me, "It was a fortress mentality … the attitude of us versus them." Further evidence of government hostility came with the expulsion from Spain of Bishop Mateo Múgica of Vitoria for agitating on his pastoral visits (May 17) and of Cardinal Pedro Segura, archbishop of Toledo and primate of Spain (June 16).[2]

In the Basque Country the superiors of urban religious communities asked for police protection. Their fears increased after a fire of suspicious origin at the Benedictine monastery of Lazkao on May 20. Strikes heightened the tension. In a general strike on May 26 and 27 fishermen, workers, women, and children from Pasaia marched on San Sebastían. Police gunfire killed six and wounded scores.

In June this tension found an outlet in religious visions in Mendigorría, a town of 1,300 inhabitants thirty kilometers southwest of Pamplona in the Spanish-speaking

part of Navarra. In 1920 in the adjacent town of Mañeru children had had visions of a crucifix moving. Mendigorría, like Mañeru, was a devout town that produced many religious vocations. On 31 May 1931 the Daughters of Mary attended a mass with a general Communion and a sermon by a Capuchin from Sangüesa. In the afternoon, accompanied by the town band, they carried an image of the Virgin through Mendiogorría.[3] On the evening of Thursday, June 4, the feast of Corpus Christi, the village priests were in confessionals preparing children for the Communions of the first Friday and the town band was playing in the square. The month of June was dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and this image was on a table in the church. A girl went in and saw an unearthly woman in mourning clothes kneeling on a prayer stool before the Sacred Heart. Frightened, the girl told her friends outside. A group went in, saw the woman, and went to tell others. More girls, including younger ones, then went in, saw nothing, and started to pray the rosary. According to one of the children, the schoolmistress told them they should pray for Spain, because it was in a bad way. When the prayer leader reached the phrase in the Litany "Master Amabilis," she said she saw the figure, and then many of the others girls cried out, "Look at her!" Some saw first a bright light on the little door of the tabernacle. Others saw only a brightness. Others, including the adults present, saw nothing. One adult told the girls to ask the Virgin what she wanted, but all they could get out was, "Madre mía." One girl fell over a chair when, she said, the Virgin called to her. And she saw the Virgin run onto a shelf between two altars. A seer, then nine years old, told me in 1988 that she saw the Sacred Heart tremble, then "a brightness; it seemed to us to be the Virgin of the Sorrows." At the time she felt a strong, sad feeling in her heart. She still thinks the vision was real, but she does not want me to use her name, lest her family think her loony.

Men in the church alerted the priests and rang the bells. After questioning the girls, the parish priest reported to the assembled town what they had said, assured them that he would inform the bishop, and led cheers for the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the Catholic religion, the Virgin, and the Jesuits. The church stayed open until midnight, a vortex of emotions.[4]

Two days later El Pensamiento Navarro of Pamplona broke the story with a letter from a villager to a relative in the city. Subsequently, the newspaper carried a more cautious version, which the clergy clearly influenced if not composed, leaving open the possibility of an "obsession" on the part of the girls. One seer told me a priest had offered them candy and told them to say that it was a lie, that otherwise they would have to go to jail; but the girls refused and swore they were telling the truth.[5]

In addition to at least twelve girls roughly nine to fourteen years old, there was a boy seer as well. Lucio, thirteen years old, was an "outsider" who had recently arrived in town. His mother was originally from Mendigorría and his father came from a village near Madrid. The boy worked as a cowherd and

said—whether before or after June 4 is unclear—that the Virgin had also appeared to him in the countryside. On June 4 he was standing in line for confession and he too saw the Virgin as a mourning lady.

The next day the Vincentian Hilario Orzanco, director of the juvenile magazine La Milagrosa y los Niños, visited the house in Mendigorría of the Daughters of Charity. In his magazine he described the visions as a reward from the Virgin to the girls who had left the music in the square to pray for Spain before the altar of Mary. He pointed to their seeing the Virgin herself in sorrowful prayer before the Sacred Heart and the Eucharist as evidence that she was interceding for Spain and he held up her prayer as an example for his child readers, intimating that they too would have visions if they were good.

To Her, then, we must address ourselves in these days of trial with a heart contrite for the sacrilege and horrible profanation of the Holy Eucharist and its churches. The profound sorrow of the Virgin, as seen in her mourning clothes and her weeping face, should make us turn inward and sweetly oblige us to atone through her for so many sins. You above all, boys and girls, subscribers to this magazine, you must dearly love the Miraculous Virgin. See how the Virgin answers the prayers of good children.[6]

Some of the Mendigorría children were subscribers to the magazine and would have read articles of a similar nature in earlier issues. As with the visions at Torralba a month earlier, those at Mendigorría did not draw many persons and had few consequences for the villagers or the seers, aside from heightening their piety and excitement.[7]

Incidents during the electoral campaign for the Constituent Cortes kept up a generalized fear in June 1931. On June 14 republicans at stations from Marcilla to Castejón assaulted a trainload of Catholic activists returning to Zaragoza from a demonstration in Pamplona. And in Mendigorría itself on the eighteenth, two weeks after the visions, villagers ambushed a busload of republicans with stones and staves. Police had to rescue two republicans marooned on a rooftop, and six others had to go to hospitals in Pamplona for treatment.[8]

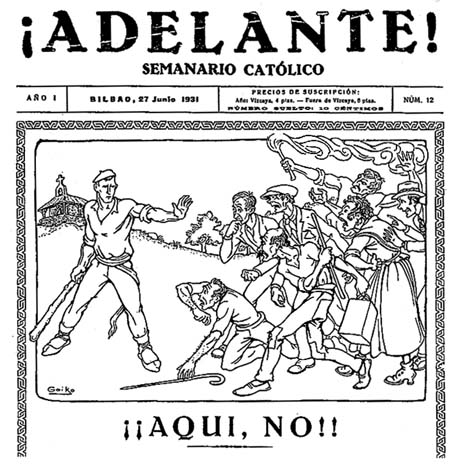

An example of the way Catholics in the Basque Country reacted to all these disturbances was a cartoon on the front page of a Bilbao weekly the day before the election. The drawing shows a single Basque country youth with a club holding off a group of ill-clad urban riffraff carrying burning torches and heading for a rural chapel. The caption read "Not Here!!" An intemperate article railed against immigrant and local leftists.

Here where little by little they have dirtied our land, where little by little they have invaded our home, where little by little they have undermined our tradition, our holy past, our mission, our honor, here, no! Those people, the accusers, the desecrators, the anarchists, cannot live together with us, because we are honorable people.

"Not Here!!" Electoral cartoon by Goiko. From Adelante (Bilbao), 27

June 1931. Photo by García Muñoz from a copy in Euskaltzaindia, Bilbao

In the elections rightist coalitions won handily in Gipuzkoa and Navarra. On that day in Bergara, fifteen kilometers from Ezkioga, electoral violence left several injured and one worker dead.[9]

It is no surprise that under these conditions on 29 June 1931, the day after the elections, a woman who had to stop her car because of a crowd on the highway near Ezkioga thought that some kind of political incident, or explosion, or assassination had taken place. But the crowd had gathered because a brother and a sister, ages seven and eleven, claimed to have seen the Virgin. The immediate and sustained interest in the Ezkioga visions showed that this was the right time and the right place for heaven to intervene in a big way.[10]

Ezkioga is a rural township of dispersed farms in the Goiherri, the uplands of the province of Gipuzkoa. In 1931 it had about 550 inhabitants. Almost all

lived on farms and spoke Basque. The town hall, the parish church of Saint Michael, and a government school were in a cluster of houses up the hill from the highway linking Madrid and San Sebastián. Down on the road there were two other small groups of houses, together known as Santa Lucía. The western group, nearer the town of Zumarraga, included a church and a school. The father of the original seers operated a store-tavern in the eastern cluster, and many pilgrims stayed in the Ezpeleta fonda there. The visions occurred on the hillside above these buildings.

How had the Second Republic affected the people of Ezkioga? One of the changes that most pained believers was the removal of crucifixes from schools and government offices. From April 1931 until the end of 1932 the government removed the crucifixes gradually throughout Spain. Manuela Lasa Múgica was the interim schoolteacher in the Santa Lucía barrio of Ezkioga from 1929 to early 1931. She came from the village to the east, Ormaiztegi, and shared the beliefs of her pupils and their families. And so, like her predecessors, she opened the day with a prayer, led the rosary on Saturdays, and celebrated the month of May with flowers and prayers. She kept a statue of Mary and a crucifix in the classroom. But in early 1931 she had to make way for the official teacher, an outsider who did not speak Basque. The community received the woman coldly, and she needed Manuela's help to find lodging. The government instructed the teacher to remove religious images from the classroom, she obeyed, and Manuela remembers people commenting that it was a shame that the children could not celebrate the month of Mary. The Republic thus represented a change for the children of the Santa Lucía, including the two future seers, just as it did for the entire region. Perhaps more so, for the schoolchildren were virtually illiterate in Spanish. Manuela Lasa taught mostly in Basque to students who would leave school at an early age.[11]

In the Basque Country and much of the north of Spain priests and religious were an integral part of the rural and small town population. Many of them came from the more prosperous farms. They shared a common outlook with peasants and those who worked in the factories of the company towns. And all higher education was then still religious education. The universities of the region were its seminaries and novitiates in Vitoria, Pamplona, and Loyola.

This devout rural culture bore one hundred years of suspicion toward the violent anticlericalism of Spain's cities and Spain's progressive governments. The antagonism dated at least from the first Carlist War and its aftermath. In 1833 the deceased king's brother, Don Carlos, rebelled against the liberal monarchy. Carlos promised to restore local liberties and the power of the church and to rule Spain as a consensual monarch of a loose confederation of regions. The stronghold of the Carlists was Navarra and the Basque Country. Enough priests and religious threw in their lot with him that liberals identified religious in general as subversives. This was one reason for the killing of religious in

Madrid in 1835. The governments that sold off church property also sold off the peasants' common lands. In the Basque Country Carlist peasantry and the rural clergy repeatedly clashed with the commercial and working people of the cities.

The last of the three Carlist wars ended in 1876, but the party lived on, a utopian, agrarian anomaly in a Spain that was rapidly modernizing. In 1888 a branch of Carlists broke away. They called themselves Integrists and they stood for a patriarchal society in which right-wing Catholicism, rather than the Carlist dynasty, was the guiding force. More papist than the pope, their strength was in the small town gentry and clergy of Navarra and the Basque Country. Their special symbol was the Sacred Heart of Jesus, but this symbol was shared with other militant Catholics.

The Carlists in their two branches cared about Spain as a whole. Basque Carlists were allies of others in Catalonia, Valencia, Castile, and Andalusia. The literature of the time often refers to them as Traditionalists. After 1920 their chief competitors for the votes of the peasantry were Nationalists. Basque Nationalism originated in the devout commercial class of Bilbao and gradually spread to the countryside and Gipuzkoa. The men of Ezkioga generally voted for Carlists or Integrists until 1919, when almost half voted for a Nationalist candidate. During the Republic the Nationalists gained new force.[12]

Before the creation of the Second Republic the deputies representing the rural, Basque-speaking laity in the Cortes allied themselves with the monarchy; the governments of the monarchy by and large left the Basques and their traditions alone. But the Republic was different, and in the new parliament most Basque representatives were part of a small minority, which the Madrid press ridiculed as "cavemen" and "wild boars." The total lack of access to a government that rural Basques considered alien compounded their apprehension after the anticlerical violence in the rest of Spain.

Furthermore, this devout society lived cheek by jowl with another enemy—enclaves of Spanish-speaking, largely immigrant republicans, socialists, and anarcho-syndicalists in the company towns, river cities, and coastal capitals. Factories near Ezkioga in Beasain, Zumarraga, Legazpi, and Tolosa offered evidence of the shift in the economic base of the region from the agriculture of dispersed farmhouses to industry. Parish priests took on the difficult task of combating new ideas and morality with religious sodalities, sermons, and revival missions. They saw the new republic tipping the scales in favor of the long-term, ongoing encroachment of modernism.

Some of the new factories were paper mills. The tenant farm of Ezkioga where the two children had gone for milk on the night of the first visions belonged to an entrepreneur who later refused to rebuild his tenants' house when it burned down; instead he planted pine trees for his paper mill in Legorreta. Farm families were under siege, not only from the new republic and its schoolteachers but also

from industrial development. It can be no coincidence that the majority of the people who eventually had visions at Ezkioga were from the farms, not the towns or cities, of the Basque Country.[13]

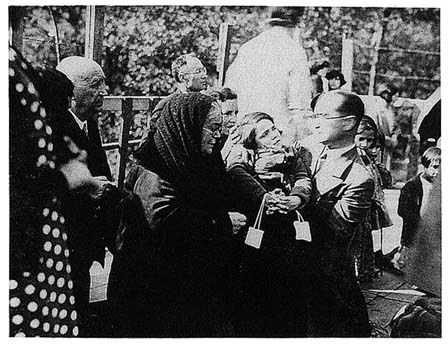

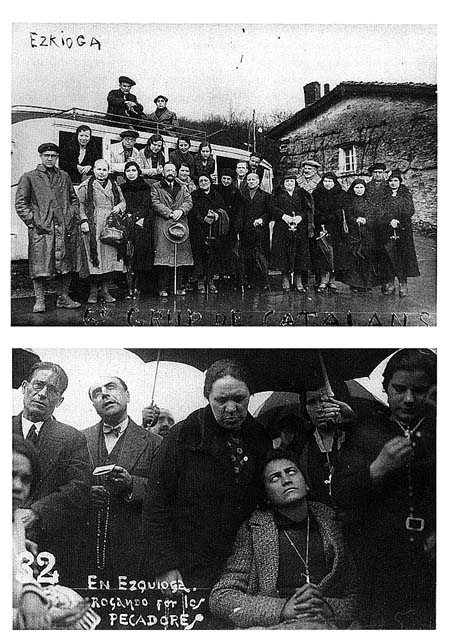

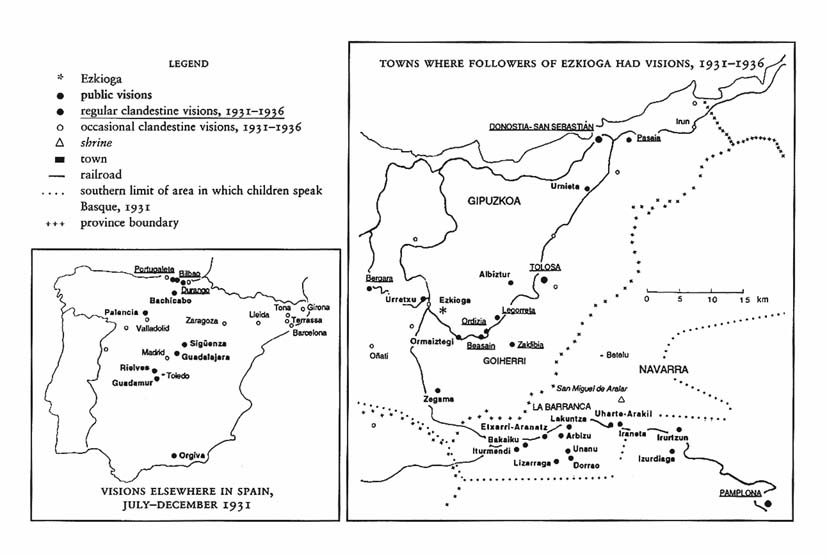

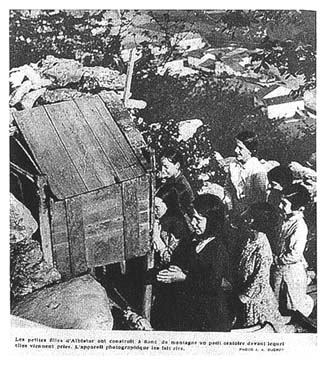

The appearances of the Virgin seemed to provide a solution to the great crisis. The first words she uttered (not to the original seers from Ezkioga but to a seven-year-old girl from Ormaiztegi and a twenty-four-year-old carpenter from Ataun) were in Basque, asking them, "Errosarioa errezatzea egunero [Pray the rosary daily]."[14] And pray the rosary people did, at night, on a hillside, often in the rain, on their knees, with arms outstretched during the Litany, while the seers waited for the visions to occur. First hundreds prayed, then within a week thousands. On the nights of July 12, 16, and 18 and October 16, up to eighty thousand persons turned out expecting miracles. In the first month there were over a hundred seers, and the visions continued in public, outdoor form until the fall of 1933. Seers at Ezkioga came especially from Gipuzkoa and within Gipuzkoa from the upland Goiherri; others came from the Basque-speaking villages of Navarra, and a few from Bizkaia, Castille, Catalonia, and the French Basque region. The visions soon spread out from Ezkioga, carried home by these pilgrims who had become seers and imitated by persons who read of the visions in the national press. Few Basques over seventy-five today did not go to Ezkioga then. It is possible that more persons gathered on that hillside on July 18 and October 16 than had ever gathered in one place in the Basque Country before.

Tapping and Defining New Power: The Press and Local Leaders

The atmosphere of rural Gipuzkoa and Navarra in June 1931 was like a cloud chamber with air so saturated that even slight radioactive emissions become visible to the naked eye. Two children whose own father did not believe them when they said they had seen the Virgin immediately attracted two to three hundred observers. In the following days, weeks, and months, in this atmosphere, other visions by other children and by adults, visions we would not normally hear about, left their marks. The impressions on these seers' minds held immense potential importance for the Catholics of the Basque Country, Spain, and Western Europe of 1931. These strong impressions are still available sixty years later in the form of memories and printed accounts.

The visions offered Catholics a source of new power or energy—power to know the future and to know the other world of heaven, hell, and purgatory, power that could heal, convert, and mobilize the faithful. The crowds that converged on Ezkioga even before the news came out in newspapers showed how much people wanted this knowledge and this intervention. Calling this power new implicitly accepts the local definition of what was happening, the

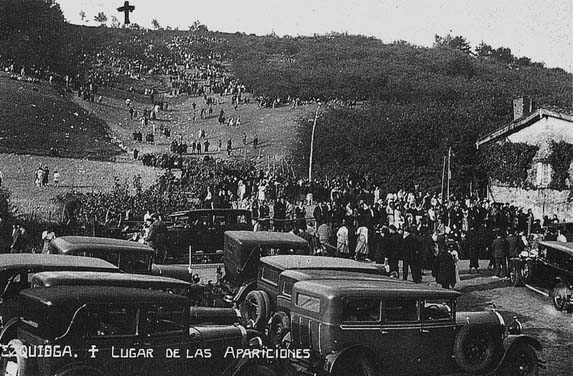

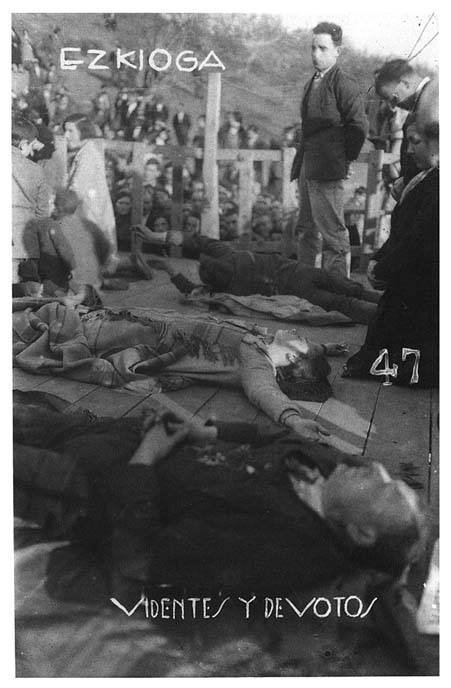

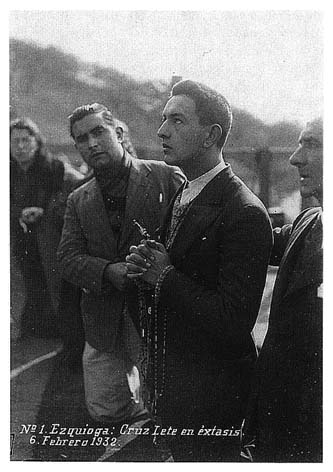

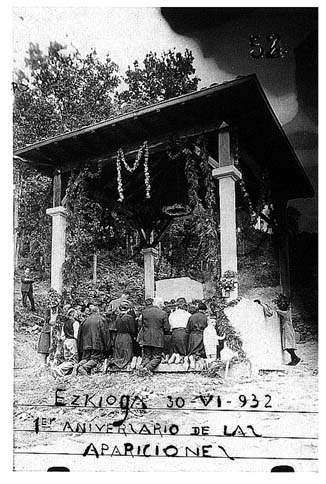

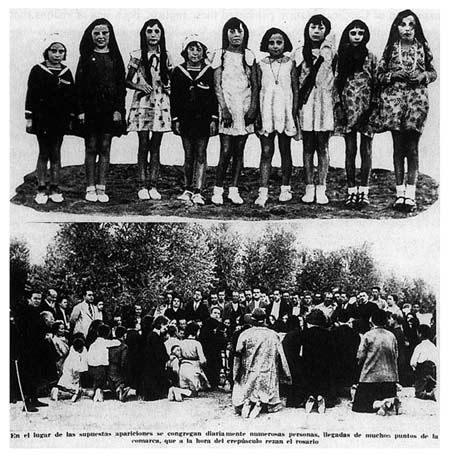

"The site of the apparitions." Crowd gathers on hillside, July 1931. Postcard sold by Vidal Castillo

truth of the divine appearances. But even believers would probably quality the idea that the power was new, because for them it would be a new version of a power very old indeed, the everyday power of God among them.

At Ezkioga this power was manifest in an unusual but hardly unique way. The Ezkioga parish church had bas-reliefs of Saint Michael appearing at Monte Gargano. Many Basque shrines had legends of apparitions. Lourdes was nearby, and well over a hundred thousand Basques had gone there and experienced firsthand the spiritual fruits of Bernadette's visions. The vision sites of Limpias (about a hundred kilometers northwest) and Piedramillera (about fifty kilometers south) were even closer. And Basque children knew about the apparitions of Fatima. The Ezkioga visions occurred during a period of enthusiasm within Catholicism in which the devout, in the face of rationalism, had come to believe that the old power was closer at hand, certifiable miracles were fully possible, and the supernaturals were easier to see.[15]

This kind of power came from the conversion of potential to kinetic energy. The potential energy lay in the Basques daily devotions, their normal attention

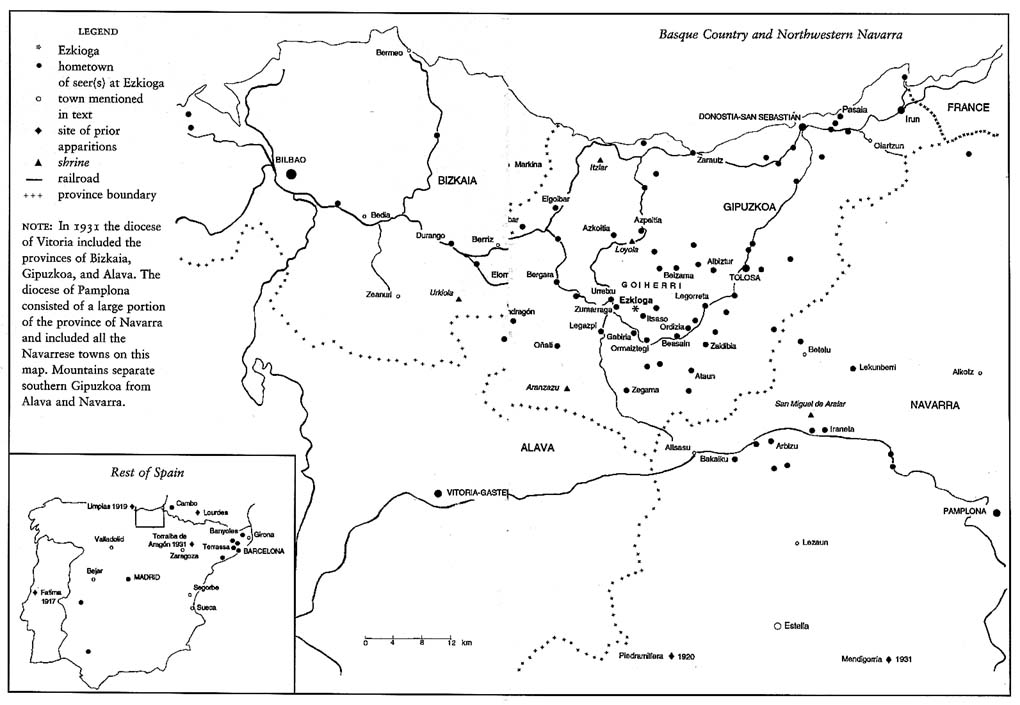

HOMETOWNS OF SEERS OF EZKIOGA AND TOWNS WHERE THERE WERE PUBLIC VISIONS

FROM 1900 UNTIL THE VISION AT EZKIOGA BEGAN ON 29 JUNE 1931

(map is on previous page)

to local, regional, and international saints. They deposited and invested this energy in daily rosaries, novenas, masses, prayers, and promises. They banked it through churches, shrines, monasteries, and convents. The church in its many representatives husbanded and administered it. The threat of the secular republic mobilized this accumulated devotional energy in the people of the north.

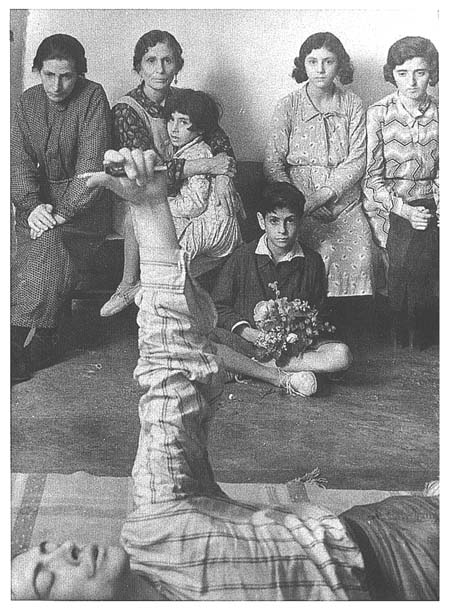

Tens of thousands of persons focused this power intensely on the seers. The seers were the protagonists, their stories and photographs in newspapers. Many of them seemed to feel in their bodies a tremendous force. Walter Starkie, an Irish Hispanist who wandered into Ezkioga and became for a few days in late July 1931 its one precious dispassionate witness, described a girl in vision as he held her:

I could feel the strain reacting upon her: every now and then a powerful shock seemed to pass quivering through her and galvanize her into energy, and she would toss in my arms and try to jump forwards. At last she sank back limp and when I looked down at her white face moist with tears I saw that she was unconscious.[16]

As we will see, time and again beginning seers described blinding light and fell into apparent unconsciousness. The metaphor of great power was one that they themselves used. When they lost their senses, wept uncontrollably, or were blissful, they demonstrated this energy to observers.

How was this power tapped? Which visions made it into print and which are available only in memories? Who by controlling the distribution of news of the visions helped define their content? How did what the seers saw and heard come to address what their audience wanted to know?

The Basques and the Navarrese were more literate than most Spaniards. In 1931, 85 percent of Basques and Navarrese aged ten or older could read and write; the percentage was about the same for women as for men. The national average was 67 percent. Parents took elementary school seriously and teachers were important members of the community. This high rate of literacy ensured many avid readers for news of the Ezkioga visions.[17]

For most Spaniards the news came largely from the reporters of the rightist newspapers of San Sebastián and Pamplona. In addition, the small-town stringers of these papers occasionally went to Ezkioga with busloads of pilgrims. Only on two occasions in July did writers for the more skeptical El Liberal of Bilbao go to Ezkioga, and there were no such eyewitness reports in the republican La Voz de Guipúzcoa .

The Basque newspapers covering the visions were those who had supported the winning coalition of candidates for Gipuzkoa in the Constituent Cortes, the parliament in Madrid that would draw up a constitution. La Constancia was the newspaper of the Carlists and Integrists; its deputy was Julio Urquijo. Two priests had recently founded El Día , the newspaper that reported the visions in greatest

detail. The Catholic press reprinted El Día 's stories throughout Spain. The newspaper was discreetly pro-Nationalist, with emphasis on news of the province of Gipuzkoa, and its deputy was the canon of Vitoria Antonio Pildain. The coalition candidates were selected in its offices. Euzkadi was the official organ of the Basque Nationalist Party, whose deputy was Jesús María de Leizaola. El Pueblo Vasco catered to the more worldly gentry of San Sebastián, and its deputy was its founder and owner, Rafael Picavea. The weekly Argia, which tended toward nationalism, went out to rural, Basque-speaking Gipuzkoa; it carried many reports on Ezkioga in 1931. News of the visions reached the public in these newspapers and their points of view affected the reporting. Even leftist newspapers depended on these sources.

While the newspapers reporting the visions were Catholic and broadly to the right, they did have some differences. The editor of La Constancia, Juan de Olazábal, was the national leader of the Integrists. In 1931 and 1932 this faction was in the process of rejoining the main Carlist party. The Integrists, "few but vociferous," had another organ in San Sebastián, the weekly La Cruz . The two factions were most powerful in Navarra, where they had two newspapers, the Carlist La Tradición Navarra and the Integrist El Pensamiento Navarro . In contrast to the readers of the Carlist and Integrist newspapers, the readers of Euzkadi, El Día , and Argia wanted an autonomous government that responded to the traditions, culture, and "race" of the Basques. For them the form of the Madrid government was immaterial, and they eventually allied themselves with the Republic and fought against the Carlists in the civil war of 1936–1939. But in 1931 the Basque Nationalist Party and the Carlists, the two main forces in the agricultural townships of the Goiherri and among the clergy of the diocese, stood together against the Republic. El Pueblo Vasco, whose Catholicism and Basque nationalism was somewhat more liberal, provided its readers with a more skeptical slant on the Ezkioga visions. While always respectful, its reporter occasionally pointed out inconsistencies and doubts. But in July 1931 its articles, some quite extensive, were largely factual.[18]

In July and early August 1931 the three San Sebastián Catholic daily newspapers each had an average of two articles daily on the visions, usually naming visionaries and describing what they had seen and heard. They also carried background articles on trances, levitation, and stigmata and on the German stigmatic Thérèse Neumann, the Italian stigmatic Padre Pio da Pietrelcina, and the visions at Lourdes, Fatima, and La Salette. Ezkioga was a big story; only the campaign for a Basque statute of autonomy surpassed it in column inches. These newspapers served as a filter. Some news passed, some did not.

Between the reporters and the seers there was another filter, that of an ad hoc commission of the two Ezkioga priests, Sinforoso Ibarguren and Juan Casares; a doctor from adjacent Zumarraga, Sabel Aranzadi; the Ezkioga health aide and the mayor and town secretary. The doctor examined those seers who came

forward, and the priests asked questions that they eventually made into a printed form. By the end of July 1931 the commission had listened to well over a hundred persons, and because many persons had visions on more than one night, the total number of visions they heard about in that month was somewhere between three and five hundred. They sometimes allowed reporters to hear the seers and copy the transcripts. The doctor guided them toward the most convincing cases. The members of the commission encouraged some visionaries to return after future visions but dismissed others. The press and the commission tended to ignore adult women seers and heed adult men, comely adolescents, and those children who expressed themselves well (see questionnaire in appendix).

The seers themselves also participated in the filtering; some of them reserved what they saw for themselves or their families and did not declare their visions. This self-censorship particularly applied to the content of the visions. Seers were especially unlikely to declare unorthodox visions. For instance, one woman told others privately of seeing something like a witch in the sky. And a man from Zumarraga told me he saw a headless figure. He added, "Don't write that down; we all saw things there."[19]

Similarly, two girls about seven years old had visions of an irregular sort in Ormaiztegi in late August and early September 1931. The father of one of the girls, a furniture maker, wrote down what they saw. On August 31 the girls said that they saw a monkey by the stream near the workshop and that two days before in the same place they had seen a very ugly woman. They then saw the monkey turn into the same woman, whom they called a witch; the witch said she understood only Basque. Directed by the father, who saw nothing, they asked the witch in their imperfect Spanish why she had come and from where. She replied, in Basque syntax and Spanish vocabulary, that she had come from the seashore to kill them. Later she supposedly ran up to the workshop and tried to attack the religious images the father was restoring.

On September 1 the two children saw the witch in the stream with a girl in a low-cut dress, short skirt, painted face, and peroxided hair who said she was "Marichu, from San Sebastián, from La Concha [the central beach]." The father made the sign of the cross and the girl disappeared, leaving the old lady, who made a rough cross in response. Later, both appeared again, coming out of the water together. The next day the Virgin appeared to the children together with figures representing the devil and temptation. The girls also saw a procession of coffins of the village dead.

These visions are a mix of Basque folklore and contemporary religious motifs, with a dash of summer sin. "Marichu" was a kind of modern woman counter-image to the Daughters of Mary. The newspapers might never have reported the Ormaiztegi visions if the church had approved the apparitions of Ezkioga. The reporter did not reveal this unorthodox vision sequence until after the tide had turned against the apparitions in general.[20]

Such journalistic suppression seems to have been common in July, when the visions had great public respectability. Starkie provides an example from the village of Ataun of the kind of vision the newspapers did not report:

I met a visionary of a more sinister kind who assured me with a wealth of detail that he had seen the Devil appear on the hill of Ezquioga … "I saw him appear above the trees—tall he was, with red hair, dressed in black, and he had long teeth like a wolf. I wanted to cry out with terror, but I made the sign of the Cross and the figure faded away slowly."[21]

Even mere spectators were aware that what others were seeing might not be holy but instead devilry or witchcraft. The word they used, sorginkeriak , literally "witch-stuff," reflected the ambiguous attitude toward the ancient subject, for it also had a looser meaning of "stuff and nonsense." Many priests preached that women should be retirado (indoors) after 9 P.M. ; thus, the woman who appeared at night on the hill was de mal retiro and going against the priests, something the Virgin would not do. This widespread opinion, more common among men, was also an indirect criticism of the women who stayed out late praying on the hillside. As long as the visions were respectable in the summer of 1931, the press rarely put such criticism into print.[22]

A third kind of distortion or molding affected the orthodox visions when certain messages were emphasized over others. The allocation of attention was the business of every person who when to, talked about, or read about the visions. In a gradual collective selective process, the Catholics of the north focused on the messages they wanted to hear. We can follow this process day-to-day through the press.

The first visions of the first seers were of the Virgin (they had no doubt who it was) dressed as the Sorrowing Mother, the Dolorosa. The image appeared slightly above ground level, and the visions were at night. Sometimes the Virgin was happy, sometimes sad, but her emotions were the "content" of the visions. On July 4 others began having visions, and during the rest of July newspapers described over two hundred of the visions in which the Virgin's wishes became more explicit. Some visionaries told how the Virgin reacted to her surroundings, to the audience, or to the prayers. Some saw the Virgin as part of allegorical tableaux. Others saw her move her lips. And starting on July 7 still others heard her speak. Visions involving acts, such as cures or divine wounds, developed only in later months.[23]

The rosary, a fixture of the gatherings, began on the third day of the visions. During and after the rosary the audience engaged in a kind of collective blind dialogue with the holy figure through the seers: on the one hand, the prayers and Basque hymns; on the other, the seers communicating the Virgin's emotions and attitudes. The Virgin was alternately sad, weeping, sad then happy when she heard the prayers, and happy. She sometimes participated in the prayers and

hymns, said good-bye, and even threw invisible flowers. Mute glances, reproachful looks, sweating, and an occasional smile had been the main—indeed the only—content of the miraculous movements of the crucifixes of Limpias and Piedramillera.

People also deduced Mary's emotions and mission from her dress, which was mainly that of a Dolorosa with a white robe and black cape (the commission took care to establish her apparel and how many stars there were in her crown), but sometimes she came as the Immaculate Conception, Our Lady of Aranzazu, Our Lady of the Rosary, or other avatars. Some seers saw one Mary after another in rapid succession.

The communication between the Virgin and the congregation was the central drama of the Ezkioga visions in the first month, but there were other vision motifs. Visions predicting a divine proof of the apparitions earned particular attention. From July 10 there were reports of an imminent miracle. Seers' predictions overlapped, so when one miracle did not occur, people's hopes shifted to another. A rumor circulated that a very holy nun—some said from Bilbao, others said from Pamplona—had predicted on her deathbed that in a corner of Gipuzkoa prodigious events would take place on July 12. On the day before that date the carpenter Francisco "Patxi" Goicoechea of Ataun had a vision in which the Virgin said that time would be up after seven days. People understood this statement variously to mean that the miracle would take place on the sixteenth or the eighteenth. On July 12 an article appeared in El Día drawing parallels between Ezkioga and Lourdes and raised hopes for a miracle in the form of a spectacular cure. On the fourteenth Patxi again referred to a time span (un turno ) elapsing, and an eleven-year-old boy from Urretxu heard the Virgin say that she would say what she wanted on the eighteenth. On the twelfth and sixteenth of July there were massive audiences of hopeful pilgrims. The newspapers reported hundreds of seers on the twelfth, but on neither day was there a miracle of any kind. On the seventeenth the Zumarraga parish priest told a reporter he would rather talk the next day: "Let us see if tomorrow, Saturday, the Virgin wants to work a miracle; perhaps something startling and supernatural, as at Lourdes, will be a revelation for us all. Maybe a spring will suddenly appear, or a great snowfall."[24]

The Zumarraga priest's hopes in print set the stage for a day of record attendance on July 18, which the press estimated at eighty thousand persons. But the day before, Ramona Olazábal, age sixteen, was already setting up new expectations because the Virgin had told her that she would appear on the following days. No miracle occurred on the eighteenth. But Patxi heard the Virgin say she would work them in the future, and a girl heard her say that she would not show herself to everyone because people were bad; so hope for a miracle continued. On July 23 Ramona heard the Virgin affirm that she would work

miracles in the future; on the next day there was a story that another nun, this one living, had announced great events in 1931; and on the following day a servant girl from Ormaiztegi announced that the Virgin "wanted to do miracles."[25]

When Starkie was in Ezkioga, around July 28, he found local people and outsiders in a kind of suspense, waiting for a sign. On July 30 the Virgin, ratifying what most persons had already concluded, declared through Ramona that "miracles were not appropriate yet."[26] By then the seers had worn out their audience, which declined to a few thousand persons and on some days to a few hundred, until Ramona herself became the miracle in mid-October.

Visions Relating to the Collective Religious and Political Predicament

The political-religious problems of 1931, which seem to have determined the immediate positive response to the visions, were not only pressing but also collective in nature, so help from the Virgin had to be collective as well. The Elgoibar correspondent in El Día of July 18 called for a message addressed to the Basques: "Let the Mother of Heaven make her decisions manifest, for we her sons in Gipuzkoa are prepared to carry them out." Already a month and a half before the visions began, La Constancia had laid out the collective plight:

Difficult times, times of trial, sorrowful omens; disquieting doubts, bitter disillusions, anguished fright, ears and eyes that open to reality, at last.

What is happening? What is going to happen?

And in this disarray, with spirits cowed, the mind goes blank, confusion grows, and the already general malaise spreads.

The writer also proposed a solution: "We must turn our eyes to God and to our conscience and begin a crusade of prayer, fervent persevering prayer; and a crusade of penance and atonement." Three weeks before the visions started the Bergara correspondent of the same newspaper made a similar analysis:

The simple and plain folk have understood that we are in the midst of a sea of dangers, that the hurricane wind tells us that we are two steps away from the most terrible storm, from which we will hardly be able to emerge without divine help; and in sacrifice they have gone to the feet of the Virgin to pray for Spain, the Basque Country, and for the town.

At Ezkioga the Basque people "turned their eyes to God" and went "to the feet of the Virgin" to pray for collective help in a way perhaps more literal than these writers expected but in a way they and others had already marked.[27]

The first hint that the visions would address this need came in the Bilbao republican paper El Liberal on July 10. The correspondent from Elgoibar reported:

When on their return from Ezquioga these people arrive in town, they won't let you get by them. Some say they have seen the virgin [sic ] with the Statute of Estella under her arm; others claim that what she has under her arm are the fueros , without a sword. They tell us, and they won't stop, that the aforesaid virgin has a complete wardrobe of outfits of different colors, and that at her side are two rose-colored angels. Is it possible that this occurs in the twentieth century, when Spanish newspapers cross the border and carry news of Spain to the rest of the world?

The Liberal correspondent may have made up the part about the Statute of Estella (the statute of autonomy that the rightist coalition supported) and the fueros (the traditional laws of the Basque Country and Navarra that the central government abrogated in the nineteenth century). But in any case the article pointed to political issues that the right as well as the left expected the visions to address.

On 8 July 1931, writing from his hometown of Ezkioga, Engracio de Aranzadi described the first visions and suggested what they could mean. Aranzadi was a successor to Sabino Arana as the ideologue of the Basque Nationalist Party, a frequent contributor to Euzkadi , and a relative of Antonio Pildain, the deputy in the Cortes and canon of Vitoria. Aranzadi's words carried great weight in the movement, and the apparitions were almost literally in his front yard. His article "La Aparición de Ezquioga" came out in El Día on July 11 and in El Correo Catalán a week later.

Aranzadi began by stating that the supernatural and the natural orders were particularly close in the Basque Country. For the Basques, he said, there was "harmony between spiritual and national activities, between religion and the race." Sabino Arana had founded the Nationalist party because of his "deep conviction that exoticism was here impiety," that is, that Basques were religious and impiety came from the outside. In the recent election the Basques alone had stood up to the Republicans and Socialists. While in the rest of Spain candidates on the right had played down their religion, in Navara and Gipuzkoa the candidates had proudly proclaimed their Catholicism. As a result, only nine of twenty-three deputies in the Vasco-Navarra region were leftists and enemies of the church ("not Basque leftists, but leftist outsiders, encamped on Basque soil on the heights of Bilbao, Sestao, Barakaldo, Donostia, Irun, Iruña, and Gazteiz").

Aranzadi argued against Basques who favored an alliance with the Second Republic at the expense of their Catholic identity and he referred to the Nationalist cause as a religious crusade beneath the "two-crossed" Basque flag: "There is a great battle in preparation. For God and fatherland on one side, and against God and the fatherland on the other…. And to our aid heaven comes.

It seems to seek to invigorate our faith, which is attacked by alien impiety." He described the first visions, which began the day he arrived for a stay in Ezkioga, and concluded:

May it not be that heaven seeks to comfort the spirit of Basques loyal to the faith of the race? May it not be that heaven seeks to strengthen the people, ever faithful to their religious convictions, in the face of imminent developments? Is it so strange, given the path we believers have taken, that to the calls of a race, of a nationality which with its blood has sealed the sincerity of its faith, a response should come from above with the help that we seek?

Aranzadi expressed the belief of many Nationalists that Mary supported the Basques against the Republic. For instance, the pro-Nationalist weekly Argia 's first article on the apparitions concluded, "God has great good will toward the Basque people." And in the next issue the Zarautz correspondent described how going to pray at Ezkioga had the effect of increasing Basque Nationalist fervor: "At this mountain the lukewarm get hot, and the hot get all fired up for Euskadi to be free and live in Her love." Throughout the month the visions of certain seers, particularly Patxi Goicoechea, himself a Nationalist, confirmed Aranzadi's diagnosis of heaven's intentions. The Virgin was preparing the Basques for a civil war.[28]

On July 14 Patxi saw the Virgin with a severe expression bless the four cardinal points with a sword. Leftist newspapers, which until then had made fun of the visions, quickly asked the government to intervene. Rightist papers countered that the visions were harmless and that it was natural that the Virgin, who as the Sorrowing Mother had a sword through her heart, should use the sword to make a blessing. On July 16 Patxi saw an angel give the Virgin a sword. The Virgin, holding a Christ with a bloody face, wept.[29]

Allegories of justice and vengeance continued on successive days. On July 17 a nineteen-year-old girl from Pasaia also saw the Virgin with a sword and a man saw the Virgin threaten him with her hand. Patxi began to reveal matters that reporters decided not to print: "The youth from Ataun told us many more things that we prefer not to mention, as they might be wrongly interpreted"; "Francisco Goicoechea made revelations of great importance which will be reserved for the time being." At the end of the month Patxi "specified certain revelations" that a writer did not "consider prudent to reveal."[30]

But the press described ever more explicit tableaux. On July 18 the Virgin blessed the audience with a sword, which she then gave to the attending angels. The next day the republican Voz de Guipúzcoa denounced "the manipulation of a hallucination" as part of a "rightist-separatist" plot and the provocation of "hatred and civil war." And a republican deputy warned in El Liberal of Madrid that Ezkioga was the product of clergy "ready to hitch up their cassocks, shoulder

their guns, and take to the hills." On July 25 an assiduous seer, an eleven-year-old boy from Urretxu, saw angels with swords that were bloody, and on July 28 so did Patxi.[31] Starkie was present at this vision and heard Patxi describe it to the priests. He revealed what the press suppressed, that Patxi said openly that

there would be Civil War in the Basque country between the Catholics and the non-Catholics. At first the Catholics would suffer severely and lose many men, but ultimately they would triumph with the help of twenty-five angels of Our Lady.

Starkie also described the mood of monarchist pilgrims expecting momentarily an uprising in Navarra against the Republic. They encouraged, supported, and chauffeured selected seers. The theme of imminent war became a permanent part of the visions. On August 6 or 7 Juana Ibarguren of Azpeitia saw the Dolorosa with sword in hand, a river of blood, and Saint Michael the Archangel with a squad of angels running quickly along the mountaintops, as if fending off some invisible enemy.[32]

Carlist as well as Nationalist newspapers reported the tableaux of celestial wars. Engracio de Aranzadi notwithstanding, Basque autonomy was less an issue in the press reports on the visions than the mobilization of Spaniards in general. For the newspapers of Pamplona and La Constancia of San Sebastiín, the upcoming battle was not to secede from Spain but rather to reconquer it. Indeed, as early as the morning of July 9, a rumor circulated to the effect that the Virgin had said to the child seers, "Save Spain." In mid-July the vision sessions included applause, shouts of "Long live Catholic Spain!" and possible monarchical vivas.

We know of these shouts because of the outrage they provoked in the Basque Nationalist Euzkadi . A priest writing on July 15 knew it was a "complete lie" that the Virgin would say to save Spain, and a week later a correspondent complained bitterly:

"Viva España la católica! Viva la católica España!" They should keep these shouts and vivas to themselves. Why didn't they go and put out the fires in the convents they burned in Madrid and Seville?… [T]he ones who burned the convents were Spaniards, although many of those inside were Basques.

Because of the turn toward the salvation of Spain by some seers, some of the audience, or the prayer leaders, most Euzkadi reporting was cool and reserved from mid-July.[33]

Simultaneously, Carlists throughout Spain became more interested. On July 24 a writer in La Constancia asserted that the visions had produced a sensation in the entire nation and he hoped for church approval, as at Lourdes and Fatima. The same day an article in the Vitoria Carlist paper Heraldo Alavés also emphasized Spain. This paper was the Catholic daily of the diocesan seat and, with the church hierarchy reticent about the visions, Heraldo had ignored the story

almost completely. One of the only exceptions was this article, "Ama Virgiña [Virgin Mother]," by the Catholic writer and labor organizer María de Echarri.[34]

Echarri's piece was the equivalent for Spanish Catholics of that of Aranzadi for Basque Nationalists, a kind of ideological blueprint for the visions. She herself had twice witnessed the movement of the eyes of the Christ of Limpias and thought Our Lady of Lourdes had converted her brother on his deathbed, so she was attentive to supernatural events.

Some ask why that sword in her hand. God has his mysteries. But some suspect also that God's justice is suspended over the guilty, prevaricating fatherland, over the land that was known as that of María Santísima, over the earth where the Virgin of Pilar came in mortal flesh, over Spain, which she considered one of her most cherished prizes. And that this justice the Lord has held back and placed in the hands of the most holy Virgin, so she will spare us from it if we know how to make reparation, do penance, expiate…. [The devotion manifest at the visions] gives one's heart hope for a day when the dark clouds that now hang over Spain, the tempest that now blows against our holy religion, the hurricane of cold terrifying secularism that today threatens the faith of Spanish children, will have dissipated.

The seer children from Mendigorría were brought to Ezkioga with the banner "Mater Amabilis, Salva a España." And some of the Basque seers pleaded to the Virgin to save Spain from impiety.[35]

On August 13 the deputy Antonio de la Villa, a journalist from Extremadura, denounced the political drift of the visions in the Constituent Cortes, charging a conspiracy. The cover of the anticlerical magazine La Traca reflected his analysis. Most deputies in the Cortes did not take him seriously, but by attributing political significance to the visions, de la Villa had much in common with the ideologues of the Basque press and with some of the seers. His speech produced no action against Ezkioga. But the government was already aware both of Carlist paramilitary organizations and of contacts between Basque Nationalists and monarchist military officers. On August 22 it shut down all rightist newspapers in the north and sent troops on exercise through the countryside.[36]

The Visions and the Younger Generation

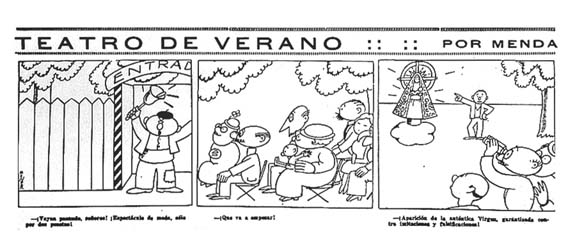

The apparitions at Ezkioga evoked an enthusiastic response in the rural devout and the urban gentry in July 1931 because everyone recognized immediately, even before there was any explicit idea of their content, the visions' potential for resolving a crisis in competing ideologies.[37] While this crisis came to a head with the proclamation of the Second Republic, the burning of religious houses, the elections of the Cortes, and the Basque autonomy movement, its long-term cause was the change from agriculture to industry and tourism.

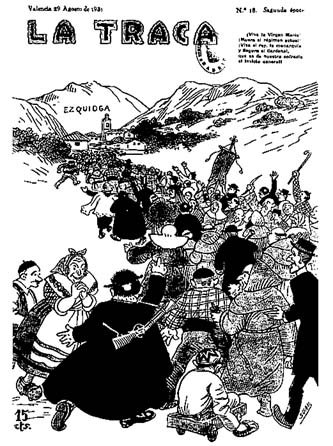

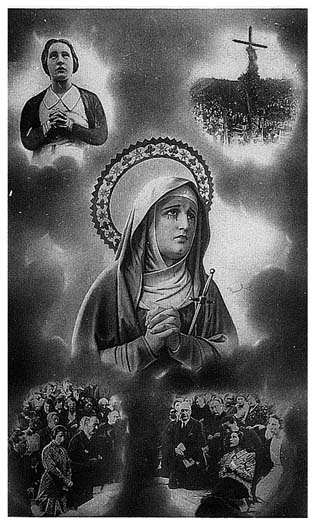

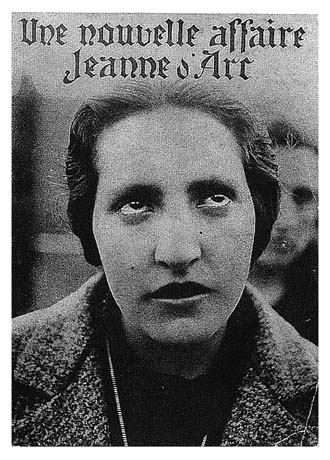

Cover of anticlerical La Traca (Valencia), 29 August 1931: "Long

live the Virgin Mary! Death to the current regime! Long live the king

and the monarchy and Segura the Cardinal, the undefeated general

of our brotherhood!" Courtesy Hemeroteca Municipal de Madrid

The Basque ethnographers of the time, who were rural clergymen dedicated to preserving "traditional Catholic ambience," presented the conflict as a struggle between rural agriculture and urban industry. In truth, small-town factory owners like Patricio Echeverría of Legazpi or Juan José Echezarreta of Legorreta (who owned the Ezkioga apparition field) were themselves of farm origin, shared these values, and counted on them to ensure their company towns a dependable workforce from the younger sons of the farms. Industrialists, it is claimed, subsidized La Constancia and kept up the fight for traditional Basque and Navarrese legal and fiscal privileges. Doubtless they financed much of Nationalist party activity as well. But whether Carlists, Integrists, or Nationalists promoted this patriarchal ideology (against, respectively, Liberals, Freemasons and Jews, and outsiders), all knew Catholic rural culture was threatened, and the diocese of Vitoria had long since geared up to defend it. Devout Basques judged the apparitions in this context.[38]

Most churchmen considered industrial urban society lost to atheism or liberalism. But they hoped they could yet contain the corrosive effects of these new ways of life on rural society. Carlists had been denouncing city life for one hundred years, but the success of Basque coastal resorts at the turn of the century caused additional confusion in rural areas and more defensive measures on the part of rural elites. In 1924, writing about his hometown of Ataun, the Basque ethnographer José Miguel de Barandiarán described the deleterious effects of contact with the cities.

Hence, many of the young people of Ataun spend part of their lives in more or less close contact with the base, tavern-going mobs of the cities and see the ostentation and show of the "fine" and "elegant" public that today makes up a large effeminate caste of little brains, but which is in the forefront of style and is the prime expression of a thoughtless and sensual outlook ever more dominant in the big cities.

In the cities, he wrote with uncharacteristic luridness, "the flower of youth wilts in sumptuous orgies and … lewd old men paint their faces and dye their white hair."[39]

San Sebastián, in particular, with its fashionable beachfront, provoked rural antagonism, which can be seen in the Ormaiztegi vision of "Marichu" from La Concha arm-in-arm with a witch. In San Sebastián at the beginning of the Second Republic there was an upsurge of sexually explicit literature. Even the republican newspaper called for "liberty in laws, but morality in customs." Some saw this immorality as the result of a breakdown of parental authority. Consider one priest's analysis of the reasons for the relatively low church attendance in the factory town of Eibar.

There is a total absence of family life: in Eibar paternal authority barely exists; "democracy and equality" have reached the intimacy of the home where people go their separate ways—more like a boardinghouse than a home. The house serves only to satisfy physical needs; apart from this all go out to the street, the bar, the café, the political club, or the movies, and this every day, in turbid promiscuity of sexes until very late at night, with dire consequences for morality and religiosity.

The clergy saw this kind of city life as a threat to the souls of rural youth.[40]

At first glance the challenges to authority in the countryside seem trivial and incidental. For they had less to do with strikes and revolts than with family and community matters like deference, social control, and gender. Examples include couples' close-dancing (a threat to parental control of courtship); women's wearing more revealing clothes, riding bicycles, or staying out later at night (threats to the authority of husbands or parents); lack of deference to the priest as measured in public reverences or greetings; and lack of deference to God and

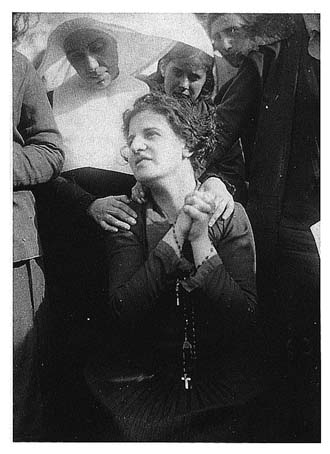

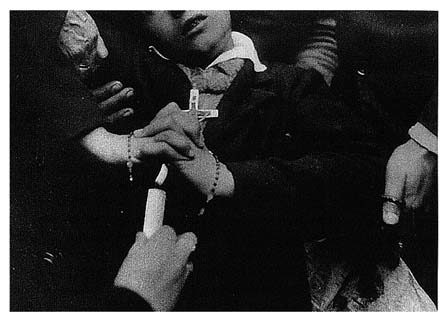

Daughters of Mary in tableau at Vitoria, February 1932: "The

Angelus prayer for the missions interrupts farm work." From

Iluminare, 20 February 1932, p. 57. Courtesy Instituto Labayru, Derio

the Virgin Mary with the abandonment of the family rosary or prayers at daybreak, noon, and nightfall at the ringing of the Angelus. Barandiarán's students and collaborators focused on the erosion of traditional practices in a 1924 survey. His clerical correspondents considered issues like close-dancing as threats to religion and to an entire way of life.

The initial reports about the Ezkioga visions show the children, returning at nightfall with milk from a farm, kneeling to pray at the ringing of the Angelus bells. Validating traditional piety, those children immediately became emblems of the Basque heartland. At this time one could see well-off girls in Vitoria dressed as farmworkers and praying the Angelus in a tableau. The Virgin thus appeared as a reward to those who kept the faith.[41]

By the same token, small matters under local dispute could also be the basis for rejecting the visions in general or particular seers. Should women be out at night? Many men decided the visions were not real because they set an example of immorality. Similarly, an argument against the truth of the visions of Ramona Olazábal was that she liked to dance; indeed, she did so on some of the same days she had visions. We may suppose that this level of discernment often escaped the

urban newspaper reporters and on this basis local people disqualified some visionaries who had passed muster with the local commission and the press. In San Sebastián one might know, at most, if someone went to church or not. Rural folk cut finer distinctions—whether one prayed on one knee or two, confessed weekly, on major feast days, or annually, and touched one's beret or took it all the way off when greeting a priest. Local people soon knew how devout seers had been prior to their visions and whether their behavior had subsequently improved.[42]

The erosion of devotional practices and respect for authority was taking place above all in the younger generation, particularly among males working in factories or on military service and among females who went to work, at ages fifteen to seventeen, as servants away from home. By 1924 an Oñati member of the youth sodality of San Luis Gonzaga read the republican Voz de Guipúzcoa in his workshop and a girl in Ataun could prefer expulsion from the Daughters of Mary to giving up her strolls with her boyfriend, transgressions unthinkable a few years earlier. A young freethinker who had worked as a waiter in Paris lived three doors from the first seers.[43] Girls on bicycles were also breaking the rules. An older lady in Zumarraga told me that when as a girl she rode past on a bicycle, a priest called out that he hoped she would not have the nerve to go to Communion the next day. One of her friends recalled Don Andrés Olaechea, one of the priests who led the rosary at Ezkioga, crossing the town square where a girl was riding a bicycle and muttering "Sinvergüenza, sinvergüenza, sinvergüenza, sinvergüenza [hussy, hussy, hussy, hussy]" until he was out of sight. To such women Dolores Nieto, the first girl to ride a bicycle, was a social hero.[44]

And of course the dancing issue was generational. In June 1931 in Marikina (Bizkaia), for example, the town authorities fined girls who danced closely in the modern fashion (el valseo or agarrado ). The citations referred the girls as "delinquents" for violating collective community vows. The diocesan bulletin describes how on 29 March 1931 Jesuits giving a mission led one such vow.

To the final service, held in the village square on the afternoon of Palm Sunday, Ceánuri came out en masse, 2,500 persons, with many more from the surrounding villages. It was there that P. Goicoechea, grasping the holy crucifix of the mission prior to the papal blessing, was able to ask that all, with their arms in the form of a cross, give their word to dance the agarrado no more and to preserve in pure form the traditional custom of being indoors when the Angelus is rung, and other customs that had been observed until now, and which are now seen as in danger because of the constant pressure of outsiders.[45]

One of the major battles fought by Liberals, and later Republicans and Socialists, was to relax attitudes toward sex and the body. Their correspondents chronicled the struggle in villages between the youth in favor of close-dancing and

the clergy and town councils in favor of the traditional (suelto ) varieties. In Ormaiztegi one of the issues in the changeover from an older to a younger town council in 1932 was pressure from the parish priest against close-dancing at town fiestas.[46]

Rural cinemas posed a particular challenge to the old ways, both in the movies they showed and the opportunities they offered couples for privacy. Around 1930 the diocese of Vitoria had tried and failed to stop Juan José Echezarreta, the owner of the Ezkioga apparition site, from opening a cinema in Ordizia. After the films on Sundays, youths from the surrounding villages stayed on for dances.[47]

On these issues peer pressure was the first line of defense for the church and the older generation. The main vehicle for this pressure was the Daughters of Mary, a pious association, or sodality, for girls. In some towns the priests who directed the sodality made girls who danced the agarrado wear a purple ribbon when receiving Communion. After the girl's third offense they expelled her and confiscated her medal, as they expelled those who walked alone with boys. Morality was the responsibility of the girls, not the boys. The church had less leverage over the boys; few of them belonged to the male sodality of San Luis Gonzaga.[48]

Given this generational conflict, the press and the general public quickly accorded adolescent and young adult seers prominence at Ezkioga. These seers were the good examples. Some, like Patxi, who started out mocking or skeptical, were even exemplary converts. By the same token, some of the divine messages most successful with the press and the public were those that spoke to these skirmishes in the war against modern ideas and religious laxity. The first message, "Pray the rosary daily," would have been superfluous in earlier times. But already by 1924 only the more devout households, particularly on the isolated farms, were saying the prayers. Commentators in Argia and the magazine Aránzazu suggested that the Virgin appeared in order to restore the rosary.[49]

And, of course, the physical presence of the Virgin, Saint Michael, and other saints at Ezkioga itself confirmed most overtly heaven's direct links to the Basques and the Spaniards. It was especially for this purpose people wanted a miracle that would demonstrate the truth of the apparitions and, by extension, of the divinity. Eventually the visions persisted in spite of the bishop's denunciation and the result was the undermining of church authority. At that point, the diocese as well as the government (the Republic and later the government of Francisco Franco as well) persecuted the visionaries and believers. But such was not the case in the summer of 1931, when priests stepped right in to lead the rosaries, direct the crowds, examine the visionaries, and even escort them from their home villages. In July, at least, there seemed to be an unbroken line from the divine to the Basque faithful, abetted by enthusiastic clergy, that served to confirm a way of life

seriously in question. To the extent that the visions contradicted this way of life, people did not believe them.

The more political messages from visionaries responded to the most grave and immediate source of the threat to Basque lines of authority, the Madrid government of the Republic. Unlike the monarchy, which even with Liberal governments maintained a certain divine connection and an alliance with local power, the secular Second Republic of 1931 was totally outside the lines of authority that ran from God to bishop to parish priest to male head of household, with ancillary lines for civil and industrial authorities. The standing Sacred Hearts of Jesus in prominent urban locations and the enthroned ones that Spain's Catholics had in the previous decades consecrated in parish churches, town halls, factories, and households served as storage batteries along the way. With the burning of convents and the expulsion of the bishop of Vitoria and the primate of Spain, the Republic seemed bent on disrupting these lines and dismantling these structures.

The Second Republic was not just an external enemy. There was a danger that the youth of the Basque Nationalist movement might pass to the pro-Republican Acción Nacionalista camp. Engracio de Aranzadi feared they would defect in his 8 July 1931 article. A fifth of the voters in Ezkioga had supported the Republican coalition. It was entirely conceivable that Basque youths might see the Republic as a defender of freedom of ideas and of a less restrictive sense of morality and as an ally against excesses of paternal, clerical, municipal, industrial, or male authority. The Republic was thus also an internal enemy that aggravated the division of generations. Even in rural Gipuzkoa Starkie came across heated arguments in taverns between republicans and rightist Catholics. When he played his fiddle in nearby, equally Catholic, Castile in the summer of 1931, both in Burgos and in remote villages young girls shouted out for him to play the Marseillaise, the anthem of liberty.[50]

The Catholics of the north, and in particular the Basques, perceived that their society and culture, once unified, was divided and under a violent attack from without which accentuated its internal divisions. This perception determined in part the way Basque Catholics tapped, defined, and interpreted the new devotional power generated by the visions of Ezkioga.

Taken as a whole, the many newspaper reports and analyses about the visions are quite revealing. A "fast" medium like daily newspapers, radio, or television (as opposed to the "slow" media of pamphlets, books, and letters of, say, late-fifteenth-century Italian visions) is a forum for the tacit negotiation between what is really on the minds of individuals, what material is all right to distribute, and what people want to hear. Note that from at least the fourteenth century in Europe few socially significant visions have been single events; rather, they have continued and developed over time, sometimes years, allowing for feedback even from slow media. While word of mouth was no doubt the most effective way of

spreading enthusiasm for both ancient and modern visions, the daily articles on the visions ensured for Gipuzkoa a homogeneous core of knowledge.[51]

The seers of Ezkioga were well aware of the importance of the press. Many of them made friends with reporters and wanted the press to tell their story. The seers' visions no doubt converged in part because they read about each other's experiences. Moreover, information could be quickly spread by word of mouth throughout the region. In 1931 Gipuzkoa had one of the most extensive telephone systems in all of Spain; indeed, there was a telephone office at the base of the apparition hill. The hope for a miracle created a network of friends and believers who could alert the entire region within hours.[52]

Most of the repeat seers were children or youths, who had an unparalleled chance for fame in the Basque Country, fame of the kind only the best improvisational poets, dancers, jai alai players, weight lifters, or log-splitters could hope for. And the seers were more than famous—they were important, they were part of a critical historical moment: Mary's direct intervention in their nation.

These visionaries gained power so surprisingly because they could express the diffuse yearning for miraculous change or, if you will, serve as lightning rods for the divine. In such a complex situation it is difficult to speak of individual responsibility. All who were present and hoping for apparitions had a hand in negotiating their content. On 8 July 1931, when by all reports the Virgin was simply appearing as Dolorosa, Engracio de Aranzadi publicly surmised that she was preparing the Basques for an imminent battle. Eventually the visions confirmed his expectations because many others, including some of the seers, shared them.

In part, the onlookers' concerns reached the seers in questions for the Virgin. A reporter stated that Patxi "directed at the apparition interminable questions, which were suggested to him by those around him." A skeptic observed that "many who question [Patxi in vision] themselves provide the answer, and others draw from the seer the desired response." Even believers in the visions would agree that when the Virgin responded to questions put to her, her messages thereby addressed and reflected the preoccupations of the questioners.[53]

For students of other places and times, the first summer of the Ezkioga visions may suggest the importance of the context in which "prophets" and charismatic leaders formulate and gradually fix their messages. In the Basque visions and movements, individual seers responded to general anxieties and hopes with what they said were God's instructions, but it seems clear that the messages were as much a consensual product of the desires of followers and the wider society as of the leaders, the prophets, or the saints. We will therefore pay as much attention to the audience—the Greek chorus, the hagiographer, the message takers, and the message transmitters—as to the visionaries themselves.

3.

Promoters and Seers I: Antonio Amundarain and Carmen Medina

Mary's sorrowful opposition to the Second Republic was the central interest of believers and seers at the Ezkioga visions in the summer of 1931. Press and public nudged along the evolving political message in a collective fashion. Simultaneously, another process, less collective, ensured that the seers produced messages for particular constituencies. Socially powerful organizers sought divine backing for various programs. After the summer of 1931 their projects absorbed much of the seers' attention.

In early August 1931, in the absence of a confirming miracle, the people of San Sebastián and Bilbao and their newspapers got over their first, sharp interest in the visions. Reporters tired of the same seers and the same messages. In any event the seers lost their forum. For the government, fearing a rightist military uprising, suspended most newspapers in the north on August 22. El Día, which printed the most about Ezkioga, only came out again at the end of October.[1] By then the tide had turned against the visions. After early August there was little detailed reporting of the visions and visionaries.

This decline in publicity coincided with the Radical Socialist Antonio de la Villa's attack on the visions in parliament and military exercises in the area. For whatever reason, the visionaries subsequently shied away from overt political messages.

Diaries, letters, books, and circulars by literate believers are our main sources for the following months and years. They show the extent to which the visions, like those at Limpias a decade earlier, served as a sounding board for movements and new devotions within Spanish Catholicism. This is not surprising. Catholics came to Ezkioga from all of Spain and southern France, many of them with prior agendas. A large number of visionaries continued to provide messages of great variety. Many seers were open to suggestion. Highly literate emissaries from the urban world of devotional politics latched onto particular rural visionaries or were actively sought out by them. This kind of symbiosis points us toward the mystical side of these Catholic movements and to principles governing alliances across boundaries of class, gender, age, and culture.[2]

The next three chapters recount the principal alliances of promoters and seers. Pressure from the increasingly hostile diocese, counsel from spiritual directors, and rivalry among seers and among promoters affected these alliances. Seers attempted to convince observers. Observers had to decide whom to believe. Or, if observers believed in several, they had to decide who had the most important messages. Those believers who sought to influence or to gain inside information from seers had to win them in some way. Believers drove the most convincing seers to the site, gave them gifts, and spread their vision messages. Over time, as these seers gained an ample public, they tended to address issues that were more general—at first political and later apocalyptic. Coming from the most convincing seers, such dramatic messages more easily passed the severe scrutiny they provoked. At the other end of the spectrum, the less theatrical, less convincing visionaries nonetheless each had a band of followers (called a cuadrilla ) which principally included persons who had known the seer previously—friends, family members, and neighbors—and who therefore trusted the seer. These less virtuosic visionaries spent more time attending to the spiritual and practical needs of constituents with less ideological interests.

As the popularity of the visions as a whole rose or fell, individual seers might move from one mode of response to another. A number of seers, when they started, addressed personal questions. When they became more popular, they supplied a more general public with news about political developments and the Last Judgment. If the visions then lost favor and only die-hard supporters remained, the seers responded once again to believers' personal needs.

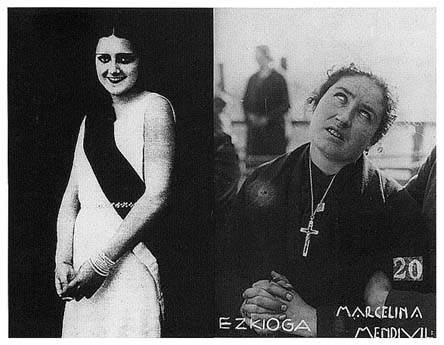

Such relationships between seers and critical believers have affected the lives and work of virtually all Catholic mystics who achieved fame, for what is at stake is fame itself. Promoters are critically important for seers whose access to literate, urban culture can only be achieved through others. We know the nobleman

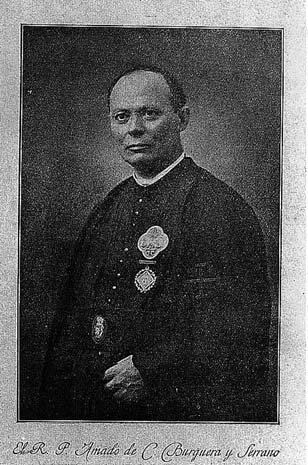

Francis of Assisi primarily through the eyes of those around him. We depend even more on chroniclers and promoters to learn about the day laborer Marcelina Mendívil of Zegama. As we look at particular learned believers and their contacts with particular seers, we gradually become aware of a far more general process by which the parties creatively combine suggestion and inspiration. As they court and separate, promoters like Antonio Amundarain, Carmen Medina, Manuel Irurita, Magdalena Aulina, Padre Burguera, Raymond de Rigné and their seers show us one way societies create new religious meaning.[3]

Antonio Amundarain

The first, crucial link between visionaries and influential believers was between the girl from Ezkioga who was the first seer and the parish priest of Zumarraga, Antonio Amundarain Garmendia. Apparitions with a broad public appeal can be halted with ease only at the very start. The parish priest, usually the first authority to deal with the matter, is of utmost importance. If he is indecisive or reacts positively, the visions can build up momentum before newspapers and diocesan officials notice them. So it was fortunate for the Ezkioga visions that the girl seer found her way to Amundarain, a clergyman influential in the diocese and fascinated by mystical experiences. The parish priest of Ezkioga and the curate in charge of Santa Lucía were far less famous and far more hardheaded.[4]

Amundarain heard about the Ezkioga visions from the woman who brought him milk. Antonia Etxezarreta, then twenty-three years old, had found out from Primitiva Aramburu, who brought milk from the farmhouse nearest the site of the visions. Primitiva had heard about them from her sister Felipa, who had been with the girl and her brother when they had their first vision.[*] Antonia was a curious, lettered woman who contributed reports in Basque to Argia . She stopped by the school in Santa Lucía to talk to the seer girl and then took her with mule and milk to Zumarraga. At the rectory she presented the girl to a curate she trusted and liked. He was inclined to dismiss the matter, but it was Amundarain who was in charge. The next day, July 2, when Antonia brought the milk, Amundarain had her tell him what had happened and that evening he went to observe the visions.[5]

Amundarain's past and character are vital to this tale. They explain why he did not dismiss the visions but instead nursed them into a mass phenomenon in the first week. A priest with intense energy and drive, Amundarain was a born organizer who was also a photographer, musician, and author of religious dramas. In Zumarraga he supervised six clergymen and three houses of nuns. He

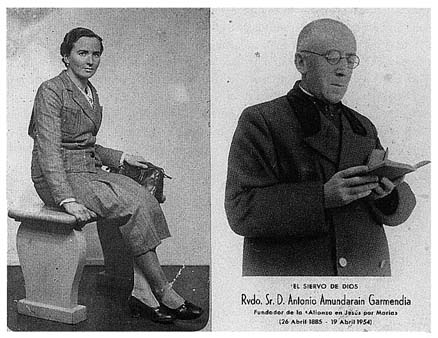

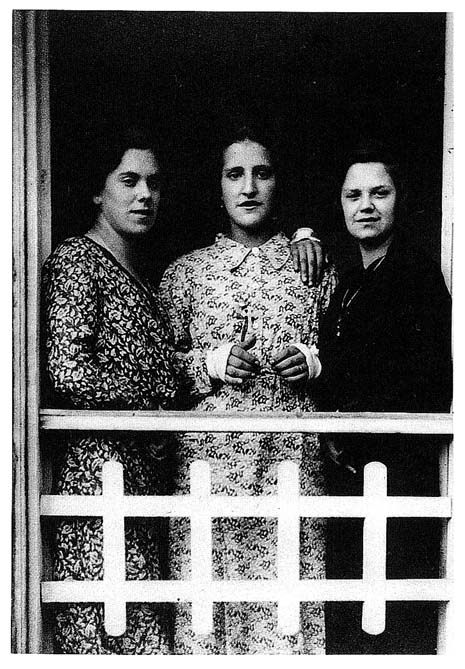

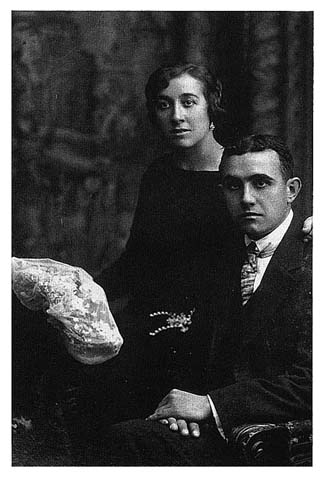

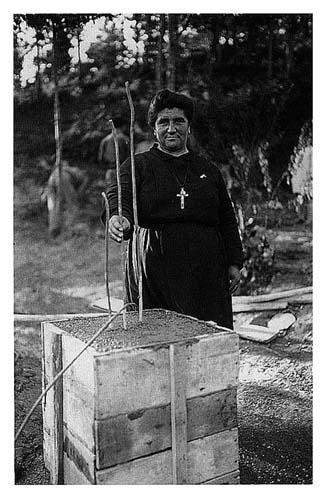

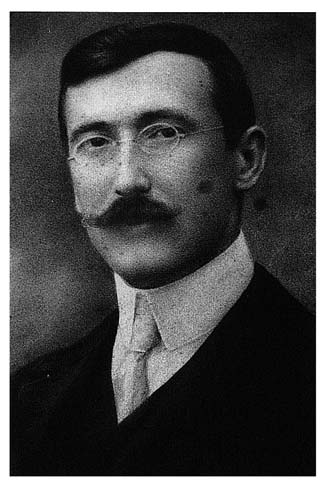

Left: Antonia Etxezarreta, the milkmaid who connected the first seer with Antonio Amundarain.

Photo ca. 1931. Courtesy Antonia Etxezarreta. Right: Antonio Amundarain Garmendia, 1948

came from the rural town of Elduain, and his father had been a Carlist soldier in the Carlist War half a century earlier. Amundarain's mother had bad memories of the Liberal household in which she had worked in San Sebastián, and her son had no yearning for the easy life of the city. One of his brothers was a Franciscan missionary in South America, a nephew became a priest, and two nieces were nuns. Amundarain himself was a Carlist-Integrist. He received La Constancia, La Gaceta del Norte , and Euzkadi . Occasionally he contributed to Argia and La Constancia . He considered La Voz de Guipúzcoa sinful. He read standing up so as not to enjoy the activity too much or waste time.[6]

Amundarain's first post had been as chaplain to the Mercedarian Sisters of Charity in Zumarraga from 1911 to 1919 and directing female religious remained his true calling. In San Sebastián, where from 1919 to 1929 he was a curate, he served as confessor to several communities of nuns.[7] There in 1925 he founded the Alliance in Jesus through Mary (La Alianza en Jesús por Maria), a lay order in which young women and older teenage girls took temporary vows of chastity and poverty, followed a rigorous dress code, and helped in parishes. By 1929 there were 207 Alliance members (Aliadas ) in twenty chapters in Gipuzkoa, Alava, Bilbao, and Madrid. By then an eighth of the young women

had gone on to become nuns. The Mercedarian Sisters came to know the Aliadas well; numerous Aliadas joined the order and the sisters helped to set up Aliada centers in the towns where they had houses.[8]

In the next two years the lay order quintupled in size, spreading to most Spanish regions. In the Basque Country Aliadas were established mainly in the provincial capitals, but there were centers in six other towns, including Zumarraga. Each section had a local spiritual director, so in 1931 Amundarain had a network of priests with whom he was in close contact. At that time the Basque Aliadas were largely from kaleak , the town centers. In the eyes of the farm people they were "señoritas [young ladies]," and I have the impression that in more rural areas many were sisters of priests. For all of the Aliadas Amundarain was a charismatic figure.[9]