Velázquez and the Golden Age

CaixaForum. Barcelona 11/16/2018 - 3/3/2019

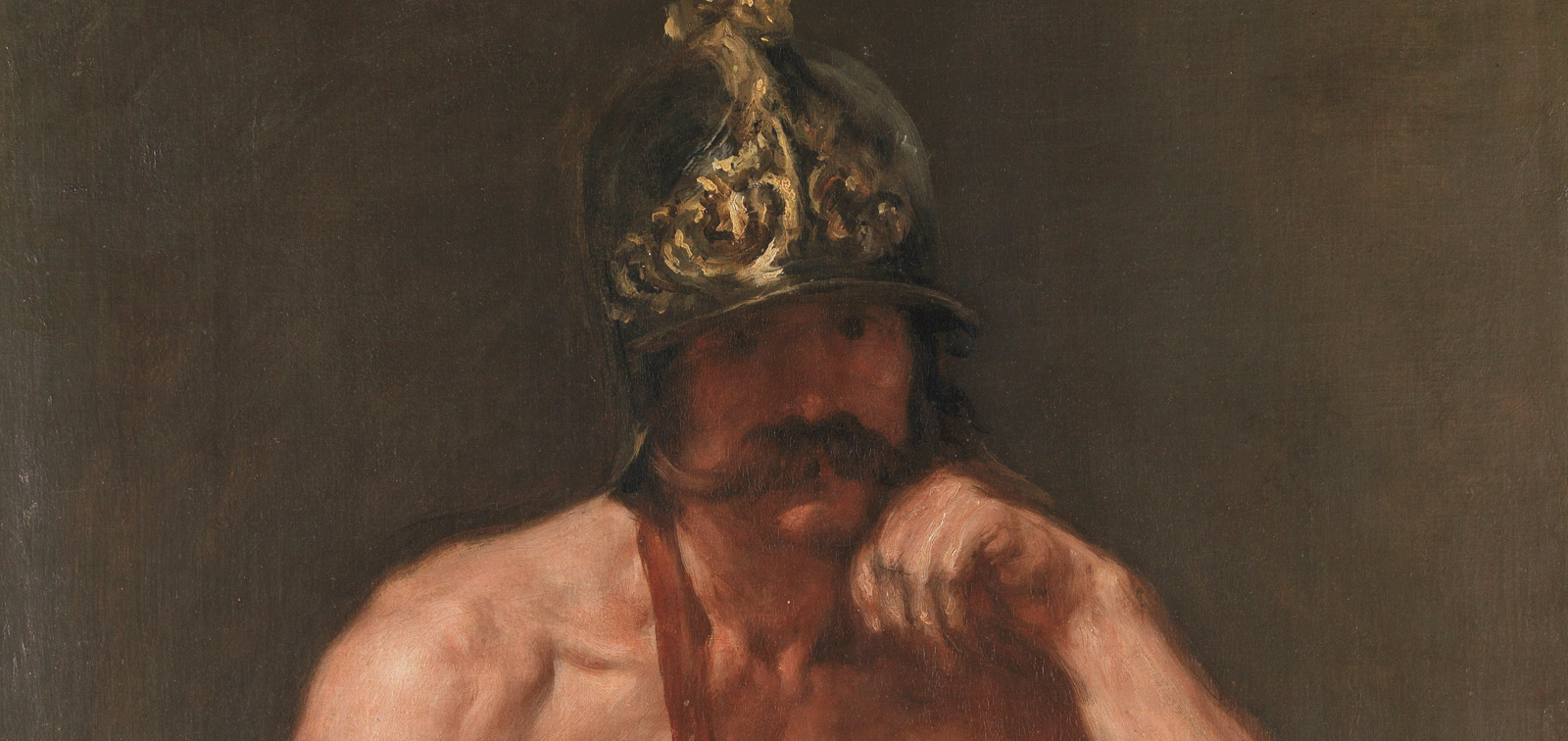

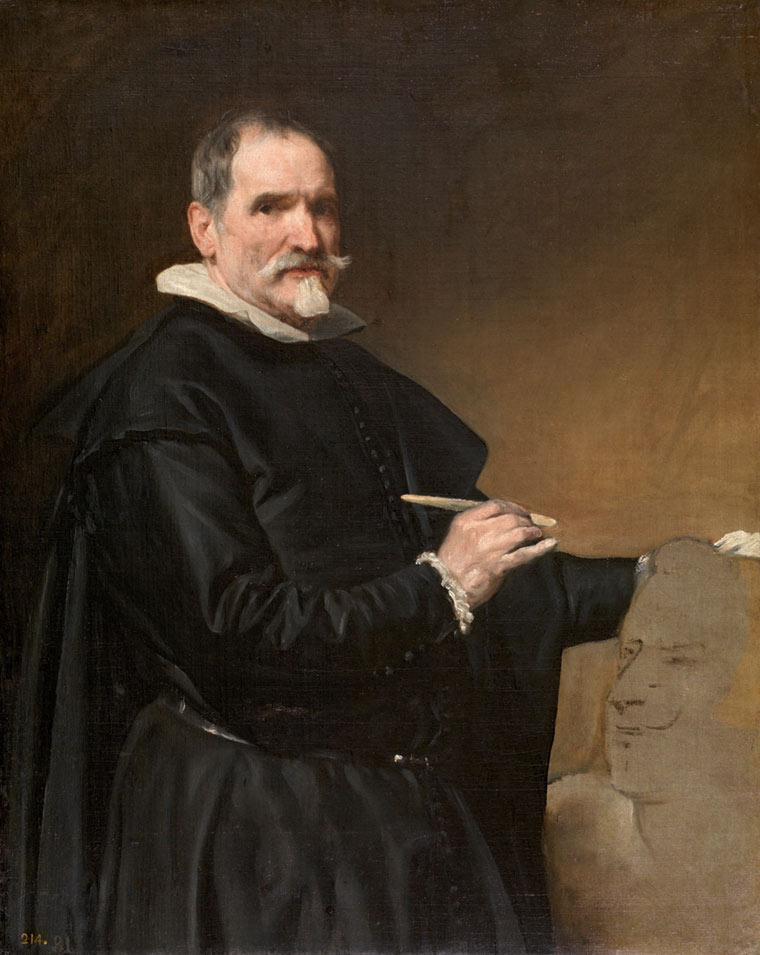

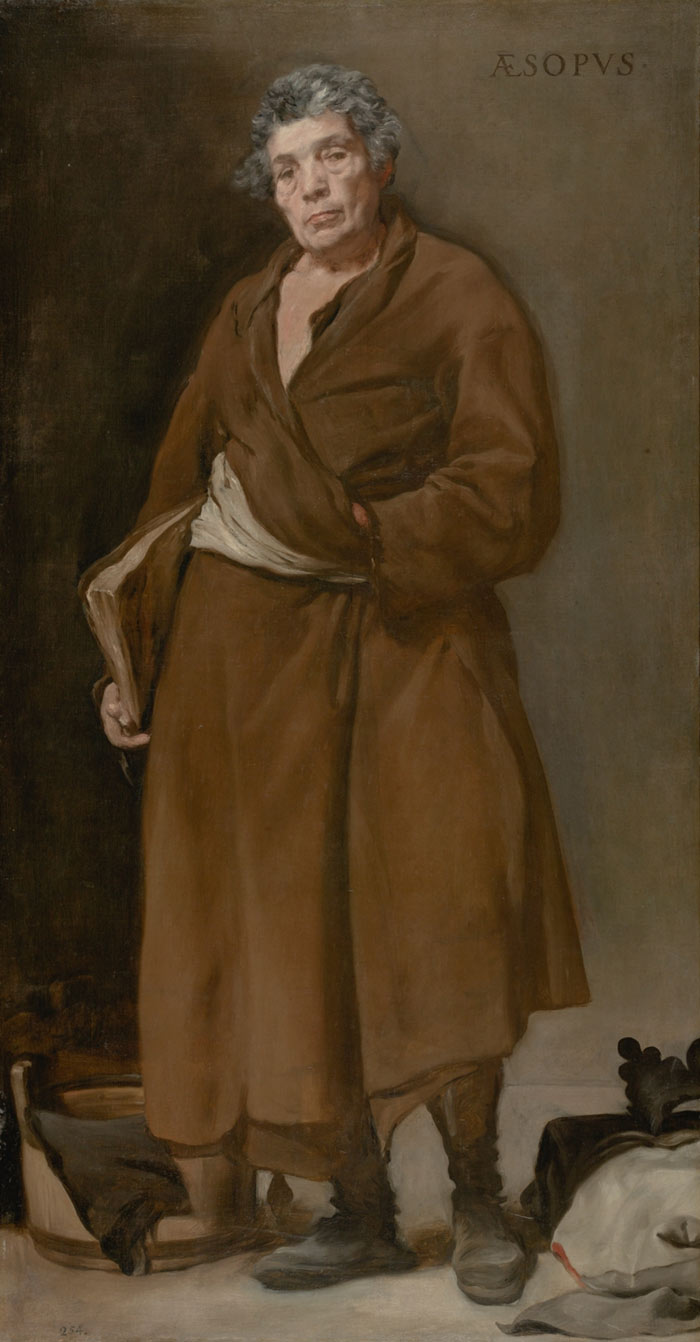

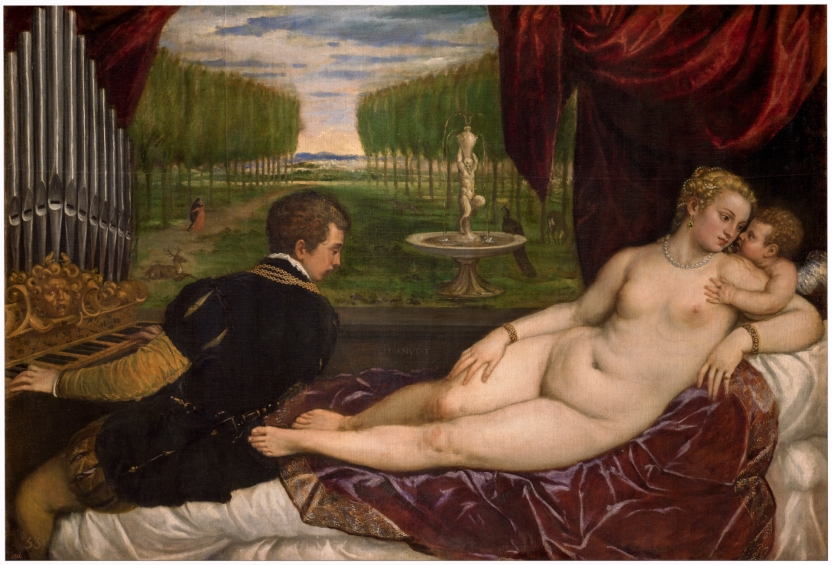

Art at the court of Philip IV was clearly an international language devoid of local boundaries. It is this international context that facilitates the best understanding of the work of Velázquez, particularly from 1623 onwards. The works that most influenced him were those by the artists best represented in the royal collections, such as Titian, Tintoretto and Rubens, and one of his key experiences was the trip to Rome in 1629 where he encountered classical and Renaissance art and established contacts with painters of his own time.

The exhibition aims to draw attention to that reality through a selection of 61 paintings associated with Velázquez, the Spanish royal collections and Spanish Golden Age painting. More than twenty of these works were painted by Italian, Flemish and French artists, including Titian, Rubens, Luca Giordano, Jan Brueghel, Anthonis Mor, Giovanni Lanfranco, Claude Lorrain, Salvator Rosa, Massimo Stanzione and Guido Reni. Spanish artists are represented through works by Ribera, Zurbarán, Murillo, Alonso Cano, Pereda, Maíno, Sánchez Coello, Mazo, Van der Hamen and others.

- Curator:

- Javier Portús, Museo del Prado Senior Curator Spanish Painting (to 1700)