Zapatistas: Lessons in community self-organisation in Mexico

As the first attempt to abolish police are under way in the US, meet the communities that have been experimenting with self-organisation, such as Zapatistas in Mexico.

As the COVID-19 pandemic has undermined healthcare systems and economies of even the most advanced nations, mutual networks and self-organizing efforts have sprung up across the world in a show of pandemic solidarity. With the police murder of George Floyd, the U.S. has seen further spread of self-organizing: from bond and mutual aid funds for protesters to citizen patrols in Minneapolis and a police-free autonomous zone in Seattle. As the first attempt to abolish police and replace it with community-based, transformative justice are underway in the U.S., we may want to look at the communities that have been experimenting with self-organization without recourse to the states that oppress or dispossess them, such as Rojava in North East Syria, Cooperation Jackson in Mississippi and Zapatistas in Chiapas. Zapatistas, in particular, have spent the last 26 years organizing their communities autonomously from the state across all spheres of life—from police and justice system to health care, economy and education. As we witness the limits of the imaginable being radically shifted, the Zapatista experience is more relevant than ever.

A student of new forms of direct democracy and stateless self-governance, I travelled to Chiapas last December to attend a month-long program, called “Celebration of Life,” that culminated in the celebration of 26th anniversary of the 1994 Zapatista uprising, when indigenous peasants of Chiapas rose up to defend their rights and land against the state and big landowners. Drawing on existing ethnographic research as well as my own interviews and conversations during the trip, I explore in this piece the most instructive features of Zapatistas’ social organization—bottom-up decision-making, autonomous justice, education and healthcare systems, and cooperative economy—in a hope that we can benefit from them when building our own “another world.”

It’s People Who Decide

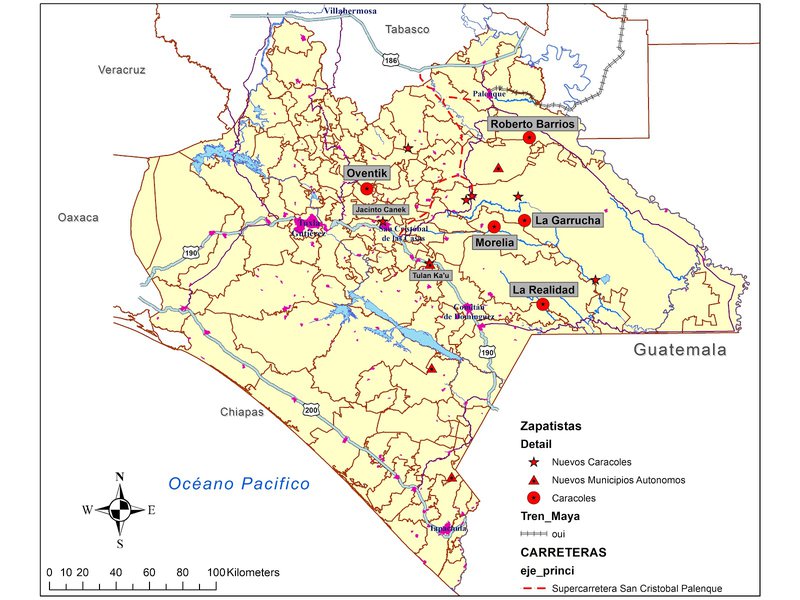

In the 26 years after the initial uprising, Zapatistas have become a leading voice of Mexico’s indigenous peoples and built a de facto autonomous system of self-governance in noncontiguous territories of the state of Chiapas, inhabited by the movement’s supporters. A key principle underlying the Zapatista project, which ensures that autonomous institutions serve the people, is mandar obedeciendo, which means to lead by obeying. It implies that political leaders do not make decisions on behalf of their community as its representatives, but rather act as the community's delegates, implementing decisions made in local assemblies—a traditional decision-making mechanism. These exist on a village level and, in contrast to traditional assemblies of Mexico, include women, whose empowerment has been at the center of the Zapatista revolution. Assemblies elect delegates to a municipal council—the next level in the Zapatista administrative structure. Next, on the regional level, several autonomous municipalities are represented through delegates in Juntas of Buen Gobierno (JBG), or Councils of Good Government—called so in contrast to the “bad” Mexican government. JBG members serve for 3 years on a rotating basis in shifts as short as a few weeks. Such frequent rotation is intended to prevent the emergence of clientelistic networks.

We’ve got a newsletter for everyone

Whatever you’re interested in, there’s a free openDemocracy newsletter for you.

Any ideas proposed at a higher administrative level go through the consultation process with each community, after which delegates carry their communities’ opinion back to a municipal meeting. There is a strong emphasis on consensus decision making, although that oftentimes means sitting through day-long meetings where everyone has to be heard, and decision is not taken until a compromise is reached. Leaders are chosen based on the indigenous tradition of cargo—an obligation to serve one’s community—and commit to unremunerated posts of responsibility. Communities have the right to revoke the mandate of those officials who do not fulfill their duty of serving the people.

The military-political formation EZLN, which had organized clandestinely since 1983 culminating in the 1994 uprising and land occupations, exists parallel to the three levels of autonomous administration and gives political direction to the movement. While it is hierarchically organized, its highest body is made up of civilians elected by community assemblies. Moreover, its presence in communal affairs has been limited in order to ensure a genuine democratic self-governance of Zapatista communities.

Having adopted a position of refusal of any aid from the so called “bad” government, Zapatistas took on the state's function of service provision in communities affiliated with the movement. That meant building their own, community-based justice, education, healthcare and production systems.

Justice System

The Zapatista justice system has gained trust and legitimacy even beyond the movement's supporters. It is free of charge, conducted in indigenous languages and is known to be less corrupt or partial compared to governmental institutions of justice. But more importantly, it adopts a restorative rather than punitive approach and places an emphasis on the need to find a compromise that satisfies all parties.

Rooted in the community, the system consists of three levels: the first level concerns issues among Zapatista supporters, such as gossip, theft, drunkenness, or domestic disputes. Such cases are resolved by elected authorities or, if necessary, by the communal assembly, based on customary practice. When resolving conflicts, authorities largely function as mediators, proposing solutions to the parties involved. If unresolved, cases go up to the next, municipal level where they are dealt with by an elected Honor and Justice Commission.

Sentences most of the time involve community service or a fine; jail sentences normally do not exceed several days. As Melissa Forbis explains, community jail is usually just a locked room with a partially open door so that people can stop by to chat and pass food. Since the perpetrator often has to borrow money for a fine from his or her family members, the latter are also involved and their pressure helps prevent further transgression. Women-related and domestic issues are addressed by women on the Commission.

Mariana Mora provides a telling illustration of the movement’s approach to punishment, documenting a case in which Zapatistas issued a year-long community service sentence for a robbery. Those found guilty were allowed to alternate service with work on their own cornfields so that their families did not have to share in the punishment. The Commission explained their decision as follows:

"We thought that if we simply put them in jail, those who really suffer are the family members. The guilty just rest all day in jail and gain weight, but their families are the ones who have to work the cornfield and figure out how to survive."

The highest level of the justice system, that of the JBG, deals with cases that primarily involve non-Zapatistas or other local political organizations—usually in disputes over land—as well as local governmental authorities. Non-Zapatistas seek out the autonomous justice system not only when they have disputes with members of Zapatista communities, but also when they experience unjust treatment by the government’s officials, in which case Zapatistas may decide to accompany the claimants to the public office and argue on their behalf.

While Zapatistas still have police, it is quite distinct from how we are used to think of it. As Paulina Fernandez Christlieb documents, they are neither armed, uniformed, nor professional. Similar to other authorities, police are elected by their community; they are not remunerated and do not serve in this function permanently. Every community has its own police, while higher administrative levels—those of municipality and region—do not. Decentralized and deprofessionalized, police thus serve and are under control of the community that elects them.

Education

The Zapatista education system is similarly community-rooted. Autonomous schools are administered by the so-called “education promoters”—primarily local youth who teach in their own communities under supervision of an education committee elected by a local assembly. Since the launch of the autonomous education system, Zapatistas have carried out training programs to prepare education promoters and develop curriculum in collaboration with solidarity groups, NGOs and volunteers from outside, as well as in consultation with the local population.

Today communities have their own practitioners who train new promoters. Just like other positions of authority and responsibility, promoters do not receive salaries and are often helped out by the community in farming their cornfields.

The curriculum is integrated in the community's life and tailored to prepare a new generation for tasks of governance and self-sufficiency, including such topics as autonomy, history, agroecology and veterinary medicine. Classes are taught in both Spanish and indigenous languages, with the emphasis on the preservation of local traditions and knowledges. Community takes an active part in determining the methodology and curriculum as illustrated in a comment by an education promoter of one of the communities, quoted by Bruno Baronnet:

"We consult our committee of education and our assembly regarding the true knowledges that are important to our people. It’s people who decide and we respect their opinion, even if sometimes I do not agree, as the other day during the assembly when I was ordered to no longer play with children during the school because some parents think that one cannot learn while enjoying oneself. I didn’t know how to tell them that it’s not at all true, but I will convince them next time. (The author's translation from French)."

Healthcare

Zapatistas have also developed their own health system, although help from non-Zapatista specialists is still used. Most communities have a local volunteer—a health promoter—who receives training in both traditional and modern medicine in Zapatista-organized regional health centers. These volunteers provide basic services in a local casa de salud (house of health).

More advanced treatment is available in clinics located in crossroads and some of the municipal centers. The clinic in Oventic, for example, is one of the most sophisticated: it provides regular basic surgery, dental, gynaecological and eye clinics; hosts a laboratory, an herbal workshop, a dozen beds for admissions, and is equipped with ambulances. Health coordinating committees, just like the education ones, exist on each administrative level, which ensures participation of communities in administering the autonomous health system.

In mixed communities, where Zapatistas co-exist with non-Zapatistas, autonomous services are open to all. I was told, for example, that non-Zapatista parents sent their children to autonomous schools because they are known to be of a better quality. Same applies to Zapatista clinics since the lack of doctors in indigenous communities is a common occurrence.

Production: Para Todos Todo, Para Nosotros Nada

(Everything for Everyone, Nothing for Us)

The functioning of the autonomous government, schools and clinics, as well as other collective projects, is financed by earnings from cooperatives and land collectives. These are at the center of Zapatistas’ aspiration to reach economic self-sufficiency from the state and to build an economy based on equitable distribution of resources. While cooperatives and collectives coexist with family land and individual entrepreneurship, participation in collective work on a rotating basis is obligatory. There are also popular banks in the form of revolving funds that make low-interest loans to members of the support base communities. These banks generate funds that get invested in new collective projects. Some collectives are women-only and intend to provide an opportunity for women to gain confidence and participate in the social life of their communities.

Another World is Possible

As most students of the Zapatista project observe, challenges facing the movement are many. They range from defections as a result of the government’s co-optation campaign through subsidies and improvement programs, to the dependence on funding by sympathetic NGOs, to the persistence of patriarchal tendencies and internal inequalities. Yet, despite the challenges, in 26 years of their struggle for autonomy, Zapatistas have built functioning social arrangements based on bottom-up democracy, cooperation and communal justice, which place community well-being over individual profit.

Through these arrangements, Zapatista communities have secured rights, protection and basic needs that the Mexican state has denied or failed to provide them with. As Dora Roblero of Frayba, an organization that has been accompanying Zapatistas since the very beginning, recently noted, Zapatistas may be the only community in Mexico prepared to weather the pandemic—thanks to their years-long self-organization of basic services.

With the states failing to protect and provide for so many around the world, the Zapatista experience offers an inspiring community-centered alternative.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.