The rise of militancy in the province in recent decades remained under-reported by the media. The attack on Imambargah in Shikarpur has therefore come as a rude shock, along with a warning that extremist forces will now target liberal and secular forces

The terrorist attack on an Imambargah in Lakhi Darr area of Shikarpur, which killed more than 60 people, has raised questions about the pluralism of Sindh where such incidents were thought to be out of question.

The members of Shia community took to the streets to protest and several cities across Sindh remained closed for three days to mourn the incident.

Shikarpur was not restored to normalcy completely till a week after the Imambargah blast. "The city is shattered. People are in a numb state; they are depressed, unable to believe that such an incident could happen in their city," says Paryal Marri, coordinator Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) Shikarpur district.

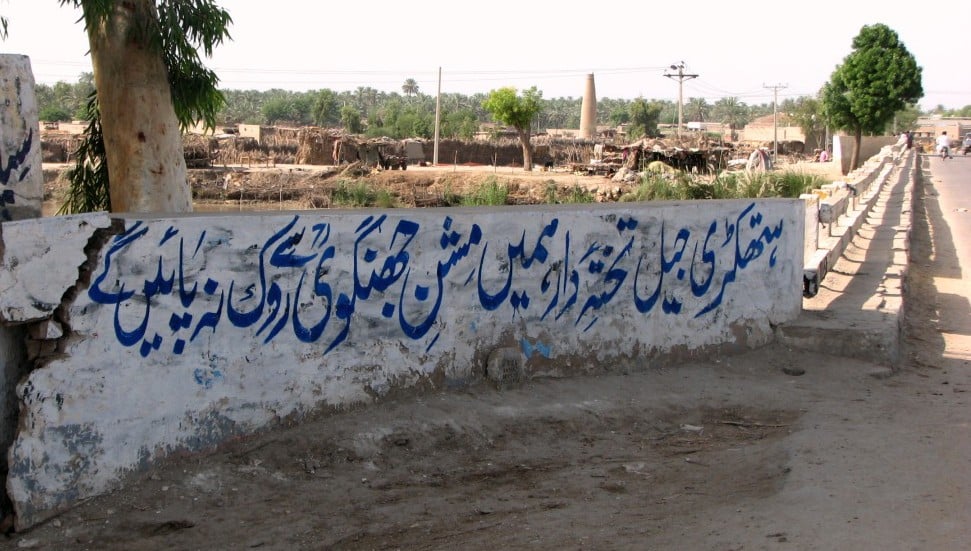

Shikarpur looks different from how it used to in the past. One can see flags of religious parties and banned organisations everywhere in the district. There’s graffiti on walls where banned organisations declare people of other sects as ‘infidels’ and give calls for jihad.

According to independent estimates, about fifty or so big madrassahs have been set up in the district in the last ten years alone.

The Lakhi Darr Imambargah incident is not the first of its kind. According to locals, extremist organisations are active in the district since early 1980s. "During former dictator Ziaul Haq’s time, extremist elements entered the district and are very strong by now," says Paryal Marri.

Terrorist attacks are not new to the district. In 2010, scores of NATO oil tankers and trucks carrying vital supplies for US-led multinational forces in Afghanistan were blown up in Shikarpur district. Outlawed Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) had claimed responsibility for those attacks.

Shikarpur is generally suffering from a worsening law and order situation. There is influx of people from the nearby Katchha area and small villages of neighbouring Jacobabad district of Sindh and also from Balochistan. And then tribal clashes are routine, due to the worsening economy, increasing poverty and decreasing natural resources. The migration of population that began in 2000 has led to rise in criminal activities including robberies at the nearby highway, murders, extortion, and even kidnappings for ransom.

Lately, the district has seen terrorist attacks. Some Sindhi nationalists blame the ruling PPP for not keeping an eye on rise in the number of madrassahs that belong to religious elements who believe in jihad. They also think the PPP-led Sindh government failed to improve basic infrastructure or provide public sector jobs, due to which poverty increased and thus the poor people in the province were attracted towards religious elements who were ready to help them financially.

This was how the radical elements started gaining ground across Sindh.

Besides, after history’s worst known flood that inundated large areas in northern Sindh in 2010, the 2012 flood in southern Sindh and the devastating drought in Thar Desert, religious groups crept into these districts silently. Falah-e-Insaniat Foundation (FIF), a sister organisation of banned Jamaat ud Dawa (JuD), started relief and rehabilitation work in these districts and still continues to do so.

Shikarpur is also the stronghold of Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam-Fazl (JUI-F). The party’s local leadership is said to have banned playing music in any ceremony in the district for the last one decade. "We are not allowed to conduct any musical concert, which is supposed to be an essential part of Sindhi weddings, cultural events and melas at Sufi shrines. Armed people come and interrupt whenever there is music," says Paryal Marri.

Shikarpur district has more than a dozen important Sufi shrines, where people from different sects and religions visit on a regular basis. Music is said to be the essential part of all rituals which is now banned by religious fundamentalists.

Militant group, Jundullah, a splinter group of Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) claimed responsibility for the Lakhi Dar Imambargah blast. But there are several groups active in the region.

Experts acknowledge their presence in Sindh for the last many decades. Independent social scientist Ayesha Siddiqa says the jihadi elements are nothing new in secular Sindh and have been there since decades. She confirms the extremists are no one except native Sindhis. "These militants are not outsiders but Sindhis themselves who are recruited."

According to her, in upper Sindh one finds Deobandi domination in the form of Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP), Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) and Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) while in lower Sindh, especially in bordering districts along the Indian border, one sees more of Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT).

"Historically there was a deobandi influence in Sindh; so it was easy for these groups to build on it. Furthermore, in the face of feudalism, an absence of narrative, and alternative power sources, there was a gap that was filled by these militants who have traction for the middle class in Sindh as much as the middle class in Punjab," she tells TNS.

Sindh, known for its progressive politics, vibrant civil society, Sufi traditions and tolerance for other faiths, has been facing threats of militancy for the last few years. The northern Sindh, that comprises different districts of Sukkur region, has become a stronghold of extremist forces. Here, a large number of madrassahs have recently been built and attacks by religious militants have been reported, especially in Shikarpur district. In 2013, there was a suicide attack on the election caravan of National People’s Party (NPP) candidate Mohammad Ibrahim Jatoi; there was another attack on Ghulam Shah Ghazi shrine in Marri village in Shikarpur; in Feb 2013, in a suicide attack, grandson of spiritual leader and custodian of a Sufi shrine, Dargah Hussain Abad Syed Ghulam Hussain Shah Bukhari was killed while the spiritual leader himself got injured. In 2013, terrorists attacked the local headquarter of ISI in Sukkur for which the TTP claimed responsibility.

Sectarian violence in Sindh has a long history. In the early 1960s, in an incident in northern Sindh’s Khairpur district, around more than a 100 participants of a Moharram procession were reportedly killed in an armed attack. Sindh’s second chief minister Allah Bukhsh Soomro, a native of Shikarpur city, was killed in his hometown.

Sindhi nationalists groups who believe in and struggle for the liberation of Sindh, instead of accepting the presence of jihadis in Sindh, term the attacks on NATO trucks as a conspiracy by the "state machinery" to spoil the secular image of Sindh. Sindh’s liberal and nationalist circles are still in a state of denial about the presence of militant groups in the region. Nationalist groups who are not separatists too have not reacted against the rising extremism across Sindh.

Some nationalists raise questions about the credibility of Pakistani law enforcement agencies who are quick to trace Sindhi nationalists holding separatist thoughts and abduct them, but can not locate the jihadis.

Analysts had already warned about Sindh falling in the throes of extremism. Zia Ur Rehman, a Karachi-based journalist who mainly covers security issues, thinks that the rise of militancy in Sindh was not being reported by the Pakistani media. "While militancy and violence in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and FATA continues to get media coverage, the northern parts of Sindh are quietly becoming the recruiting grounds for militancy," he says.

In his view these forces will ultimately target liberal and secular political forces in Sindh. "At this stage, they have targeted Shia community and Sufi shrines, but it seems their future target would be liberal political forces, especially the Sindhi nationalist groups, as they did in KP and FATA."

Steeped in history

The streets in Shikarpur are lined with heritage buildings on both sides. The buildings have unique architecture, which varies from French to Victorian to masonry brick. Many of these buildings have exceptional centuries-old mud and wood structure, with lime work, stucco tracery and brick mosaic flooring. One sees wrought-iron religious signs of Om and statues of Queen Victoria. These archaeological buildings depict the rich history of the city and show how much the residents love it.

At many places in the city, mosques and Hindu temples stand together -- a testimony of religious harmony.

According to locals, the city was once located inside a fort with around seven huge gates or entrances. Lakhi Darr is one such entrance that opens towards the Lakhi town. That is site of the Imambargah where the terrorist attack not only claimed scores of innocent people but also a centuries’ old history of tolerance.

Another entrance is named Haathi (Sindhi word for elephant) Darr. This is where, in the past when Shikarpur was the commercial hub, elephants carrying trade goods were allowed to enter.

In Shikarpur’s Dhak Bazaar (the covered bazaar) people used to keep cold water so that travellers could drink water in the sizzling summer. There is a Dewan Hotel just opposite a public park that is still known for the Hindu deity Ganesha’s name, Ganesh Park and a huge sized Bajaj Tower built in memory of Hindu businessman Seth Hiranand Bajaj.

Much before the establishment of port in Karachi, Shikarpur was supposedly the commercial hub of Sindh. Owing to the beauty and cleanliness of the city, it was known as the "Paris of Sindh". But now it is a living sign of sheer negligence of government authorities. With its collapsed sewerage system, encroachments, broken streets and dirt and dust, one can not believe this is the city that had such a glorious past.

-- A. Guriro