Alan Turing, the scientist known for helping crack the Enigma code during the second world war and pioneering the modern computer, has been chosen to appear on the new £50 note.

The mathematician was selected from a list of almost 1,000 scientists in a decision that recognised both his role in fending off the threat of German U-boats in the Battle of the Atlantic and the impact of his postwar persecution for homosexuality.

The announcement by the Bank of England governor, Mark Carney, completes the official rehabilitation of Turing, who played a pivotal role at the Bletchley Park code and cipher centre.

Q&AWhich historical figures have appeared on banknotes?

Show

William Shakespeare was the first historical character to appear on a Bank of England note in 1970. Here’s the full list of the historical characters that have appeared on banknotes issued by the central bank in England and Wales over the last five decades.

Past banknotes

1970 William Shakespeare, playwright (£20)

1971 Duke of Wellington, soldier and statesman (£5)

1975 Florence Nightingale, founder of modern nursing (£10)

1978 Sir Isaac Newton, physicist and mathematician (£1)

1981 Sir Christopher Wren, architect (£50)

1990 George Stephenson, engineer (£5)

1991 Michael Faraday, scientist (£20)

1992 Charles Dickens, author (£10)

1994 Sir John Houblon, first Bank of England governor (£50)

1999 Sir Edward Elgar, composer (£20)

2000 Charles Darwin, naturalist (£10)

2002 Elizabeth Fry, prison reformer (£5)

Current banknotes

2007 Adam Smith, economist (£20)

2011 Matthew Boulton and James Watt, steam engine industrialists (£50)

2016 Winston Churchill, prime minister (£5)

2017 Jane Austen, author (£10)

Future banknotes

2020 JMW Turner, artist (£20)

2021 Alan Turing, mathematician (£50)

Julia Kollewe

While at Bletchley Park, Turing came up with ways to break German ciphers, including improvements to pre-second world war Polish methods for finding the settings for German Enigma machines.

Carney said on Monday: “Alan Turing was an outstanding mathematician whose work has had an enormous impact on how we live today. As the father of computer science and artificial intelligence, as well as [a] war hero, Alan Turing’s contributions were far ranging and path breaking. Turing is a giant on whose shoulders so many now stand.”

The Bank praised Turing for his role as a scientist and for the impact he has had on society. Prosecuted for homosexual acts in 1952, an inquest concluded his death from cyanide poisoning two years later was suicide.

The Bank acknowledged Turing’s pivotal role in the development of early computers, first at the National Physical Laboratory and later at the University of Manchester.

“He set the foundations for work on artificial intelligence by considering the question of whether machines could think,” the Bank said. “Turing was homosexual and was posthumously pardoned by the Queen, having been convicted of gross indecency for his relationship with a man. His legacy continues to have an impact on both science and society today.”

Peter Tatchell, the veteran gay rights campaigner, said the £50 note announcement was a “much-deserved accolade for one of the greatest minds of the 20th century”.

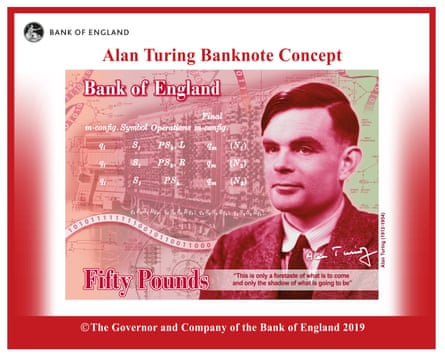

Turing’s face will appear on the new £50 polymer note when it goes into circulation in 2021, following a public consultation process designed to honour an eminent British scientist.

The Bank said it had received a total of 227,299 nominations, covering 989 eligible characters. These were narrowed down to a shortlist of 12, with Carney making the final choice.

The shortlisted characters, or pairs of characters, were Mary Anning, Paul Dirac, Rosalind Franklin, William Herschel and Caroline Herschel, Dorothy Hodgkin, Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage, Stephen Hawking, James Clerk Maxwell, Srinivasa Ramanujan, Ernest Rutherford, Frederick Sanger, and Alan Turing.

Speaking at the launch, Carney said the selection process for new notes was “as inclusive as possible.” However, MPs and campaigners had warned that choosing a white scientist risked sending a “damaging message that ethnic minorities are invisible” while on Monday the campaign group, Banknotes of Colour, said its 150,000-strong petition to have an ethnic minority on a banknote had “not been taken seriously” by the Bank.

Asked by the Guardian whether the new £50 note was a missed opportunity to reflect diverse modern Britain, Carney said the Bank wanted to celebrate “all aspects of diversity” and that “to not represent the scale of scientific achievement in this country would be a mistake”.

He added: “We want to represent as best as possible all aspects of diversity within the country, from race, religion, creed, sexual orientation, disability and beyond. What we have today is a celebration of one of the greatest mathematicians and scientists in the United Kingdom and not just this country’s history but world history.”

The note was unveiled at Manchester’s Museum of Science and Industry, a short walk from the Manchester University building where Turing helped develop programming for the Ferranti Mark 1, the world’s first commercially available electronic computer.

A new exhibition at the museum showcases several artefacts connected to the pioneering scientist, including an original Enigma cipher machine used in the second world war, electronic components for a Ferranti Mark 1 computer and a Manchester University marketing brochure from 1951 with a photograph of Turing leaning over a computer.

It was also in Manchester where the campaign to clear Turing’s name began. The original petition calling for a posthumous pardon was begun by William Jones, a computer scientist living in the city, and eventually reached 37,000 signatures, prompting Turin’s royal pardon in December 2013.

John Leech, the former Liberal Democrat MP for Manchester Withington who helped lead the campaign for a Turing law, said he was “very emotional” to see the new £50 note at the official unveiling and that it was a “massive acknowledgement of his mistreatment and unprecedented contribution to society”.

Leech said: “It is almost impossible to put into words the difference that Alan Turing made to society, but perhaps the most poignant example is that his work is estimated to have shortened the war by four years and saved up to 21 million lives.

“And yet the way he was treated afterwards remains a national embarrassment and an example of society at its absolute worst.”

While Turing would surely have celebrated the technological advances moving Britain towards a “cashless” society – more than half of transactions are now on contactless cards, compared with less than 30% when Carney became governor in 2013 – Carney insisted physical notes would remain in circulation “for a very long period of time”.