Critics Page

Filippo Brunamonti

Hidden Figures

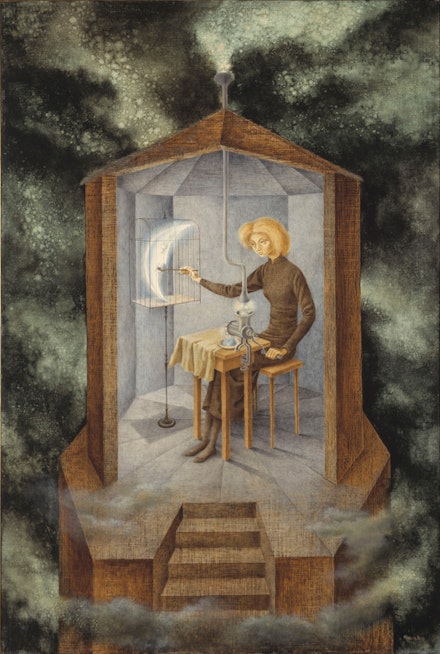

When I think about the body and mind of an artist, my mind goes to the painting Papilla Estelar (Celestial Pablum) by Remedios Varo, a Spanish-Mexican para-surrealist painter and anarchist.

Paraphrasing Whitney Chadwick ’s Women, Art, and Society (1996), in Varo’s Celestial Pablum, an isolated woman sits in a lonely tower, a blank expression on her face, and mechanically grinds up stars, which she feeds to an insatiable moon—a powerful symbol that describes the role of women in the 1950s. Women of the surrealist movement were often written off as subservient and silent. However, the surrealist movement liberated them from a patriarchal society and empowered the rise of feminist integrity both in Mexico and the United States—not only by words, but with the help of shapes, geometries, and raw material (Varo used to prepare all her masonite by herself ). Sixty years after the creation of Papilla Estelar, has the art world redressed the under-representation of artists who are women? Are there new surreal friends ready to fight and conquer that slice of insatiable moon; or, on the contrary, do they prefer to become moon chum?

Remedios Varo, Papilla estelar, (1958) Oil on board 36 x 24 inches (91 x 61 cm). Courtesy of the Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco.

For many in the art establishment, Leonora Carrington was just a muse who had inspired some of Max Ernst’s paintings. But, as evinced by journalist Joanna Moorhead, who went in search of her cousin (Carrington) in Mexico, where she had settled after the split with her lover, the English-born artist and novelist, Carrington was more than just a muse. Fiercely independent, she admitted to The Guardian that she had been instinctively influenced by Ernst, but had gone on to become a prolific artist in her own right—an artist who disappeared from view year after year, further elevating the role of the male artist in the chauvinist art circuit.

So many women artists have come to light in the past few decades, and even if the National Endowment for the Arts’ latest Artists and Arts Workers in the U.S. study shows that the number of arts workers are split nearly fifty-fifty by gender, the more we dig into the statistics, the more disparity we can still find between men and women in the arts. Thirty percent of gallery-represented artists are female, twenty-five percent of New York solo gallery exhibitions feature women, twenty-four percent of museums with an annual budget over

$15 million have female directors, and the wage gap between male and female artists/arts workers is at nineteen percent. To date, there are only a handful of women on the highest-selling individual lots for living artists. Artworks made by women often make up only three to five percent of permanent collections in the U.S. and Europe. Of 590 major solo shows held stateside between 2007 and 2013, only twenty-seven percent were devoted to women, according to a survey by The Art Newspaper.

The recently released 2017 report by the Association of Art Museum Directors

(mentioned by PBS), gives a face to the power structures:

“At museums with budgets exceeding $15 million … men hold seventy percent of positions. Women fare better in smaller budget museums, and overall, women now represent almost half of all directorships. But they still make less money than men in those positions.”

Numbers aside, today, few people can name five artists who are women and have had a huge impact in the world. Can you?

Contributor

Filippo BrunamontiFILIPPO BRUNAMONTI is a contributor to the Brooklyn Rail