Tags

A recent Guardian article shone a light on a little-visited area of Lima, and investigated a claim that this is the birthplace of punk music. Lince is a district in Lima between Miraflores and the centre, and one I regularly walk or take a bus through on my way to town without much thought. After reading the Guardian’s story of Peruvian band Los Saicos’ origins here and their influence on punk music, I was keen to delve further into this musical mystery.

A recent Guardian article shone a light on a little-visited area of Lima, and investigated a claim that this is the birthplace of punk music. Lince is a district in Lima between Miraflores and the centre, and one I regularly walk or take a bus through on my way to town without much thought. After reading the Guardian’s story of Peruvian band Los Saicos’ origins here and their influence on punk music, I was keen to delve further into this musical mystery.

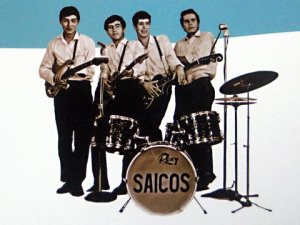

Briefly then, the article claims that Los Saicos (The Psychos), whose members are now all in their sixties, pioneered punk music before the likes of The Sex Pistols or the Ramones, and created ‘a sound that was 10 years ahead of their time.’ Writers Jonathan Watts and Dan Collyns mention the marble plaque put up in Lince by the government which proclaims global punk music to have been born in the area. In usual inquisitive style – and because I didn’t have other plans for an overcast Saturday morning – I set about trying to track down the plaque and seeing what else I could unearth about Saicos. After a brief Googling session to locate the plaque failed, I returned to the trusty Guardian website and watched the short video accompanying the article. By pausing the film on one particular shot I could just make out the names of the 2 streets where the plaque is positioned, so after noting these down and arming myself with a map I set forth on foot to hunt those Psychos down.

A couple of blocks from the main thoroughfare to the centre, on the corner of Av.s Marsical William Miller and Julio Cesar Tellos (don’t these names just trip off the tongue?) lies a grubby, rundown-looking line of apartments. At street-level, affixed to the wall on the end of this row, lies the marble plaque. After photographing it and trying and failing to decipher the Spanish inscribed I hung around the commemorative sign, unsure of what my next steps should be. As the alleged birthplace of punk I admit I had half expected to see some safety-pinned, Mohican-ed youths, or an impromptu street performance of thrashing guitar and screaming expletives. As I glanced around, I saw only shifty-looking men in need of proper clothes and personal hygiene advice, as well as mangey dogs who probably would have benefitted from the same. (For loyal readers, dogs in Lima often sport canine clothes: check out my earlier post).

Since last weekend I managed to contact Diego Ugaz, Press Chief and former Manager of Saicos. My questions have also been forwarded to the band members but I was warned that they can be slow to reply to emails. So in the meantime, Ugaz was able to give me information to help in my investigation and challenge some of that reported in the Guardian.

Firstly, the name of the band – which the Guardian writers repeatedly stated as Los Saicos, I was told was in fact Saicos: take that, Guardian. Instead of pioneering punk music, Ugaz explains that Saicos established a protopunk sound, free of the ‘attitude of contestation, ideals and pure anarchy in the lyrics’ and made music ‘to have fun, pure fun.’ It was not only Saicos’ type of music in the early 1960s which proved revolutionary, but the way they performed it too. The music scene in Peru was replete with bands’ covers of UK and US hits (as the Guardian describes), as well as instrumental and Peruvian ‘gogo’ bands. Saicos, on the other hand were ‘the first band to record strange protopunk music in their own language, in Spanish.’

Firstly, the name of the band – which the Guardian writers repeatedly stated as Los Saicos, I was told was in fact Saicos: take that, Guardian. Instead of pioneering punk music, Ugaz explains that Saicos established a protopunk sound, free of the ‘attitude of contestation, ideals and pure anarchy in the lyrics’ and made music ‘to have fun, pure fun.’ It was not only Saicos’ type of music in the early 1960s which proved revolutionary, but the way they performed it too. The music scene in Peru was replete with bands’ covers of UK and US hits (as the Guardian describes), as well as instrumental and Peruvian ‘gogo’ bands. Saicos, on the other hand were ‘the first band to record strange protopunk music in their own language, in Spanish.’

Saicos ‘didn’t want to sound like other bands’ and instead made ‘advanced music,’ including their hit Demolición which has been covered by other bands worldwide. Although their prime intentions may not have been to initiate punk, going against the grain and producing a new sound during this decade is still an action tinged with anarchy.

So, what of punk music in Lima today? The Guardian piece neglects to focus on the current music scene in the city, or country as a whole. As was typical, the 1980s saw the heyday of punk in Peru. Saicos’ influence was still felt, as Peruvian bands like Leusemia and Eutanasia covered Demolición, though this time the song had acquired a deeper significance. Ugaz admits this was the decade people ‘fought against the government and lived in chaos’ amidst the ‘bombing and massacre of Sendero Luminoso’ (Shining Path). The punk movement during this period addressed ‘terrorism, anarchy and confronted the government’ and reflecting on the period it is clear to see why: by 1990 an estimated 30,000 were dead, 600,000 families left homeless, and areas of the country were a wasteland.

In addition to his role with Saicos, Ugaz has hosted a music TV programme and writes for music magazines, and is skeptical about punk music in Peru today. Its ‘lack of art and movement,’ he believes can be attributed to young people’s distance from events in the 80s: ‘the new generation just doesn’t know about the terrorism that some of us lived,’ preferring instead imported US pop-punk or ‘chikipunk’ in Peru.

In addition to his role with Saicos, Ugaz has hosted a music TV programme and writes for music magazines, and is skeptical about punk music in Peru today. Its ‘lack of art and movement,’ he believes can be attributed to young people’s distance from events in the 80s: ‘the new generation just doesn’t know about the terrorism that some of us lived,’ preferring instead imported US pop-punk or ‘chikipunk’ in Peru.

Saicos’ music and their history are still hugely relevant today, and with his experiences and knowledge of the industry, Ugaz believes Peruvian musicians are learning about the band’s ‘history [and] roots, and consider Saicos as the fathers of protopunk style.’ It seems that although the ‘revelation of sound’ Saicos created was not embedded with the anti-establishment drive propelling true punk music, it provided the emergence of this sound in subsequent decades. The 1980s saw their hit tune assume an anthemic significance and, along with their recent recognition, means that the band continue to inspire musicians today.