This is the story of the Delair railroad bridge across the Delaware river, for which an edited version appeared this week in Hidden City Philadelphia. You can see the Hidden City article here. I have been intrigued with this bridge for years, as it is not well seen from anywhere along the normal river viewpoints in the city. After doing some research and photographing along the shoreline, I found the story of South Jersey’s railways and the quest for faster Atlantic City travel to be fascinating. Enjoy a trip across the big steel trusses and through the NJ Pinelands with me.

———————————————————

The Delair Railroad Bridge – A Hidden Bridge on the Delaware River

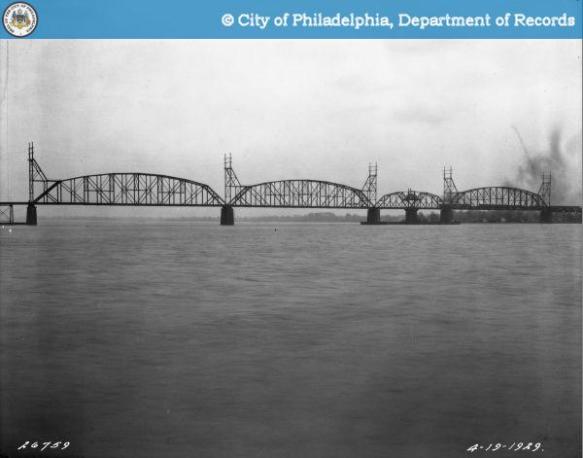

The Delair Bridge c1900; Credit: Philly History

On June 28 Mayor Kenney signed the city legislation needed to purchase the abandoned railroad swing bridge that crosses the Schuylkill just south of Grays Ferry Avenue. Work will soon commence on raising the historic Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore RR Bridge No. 1 for it’s conversion to our new SRT bicycle and pedestrian crossing to Bartram’s Mile. Abandoned since 1976, the bridge is rusting quietly in the open position waiting for a new lease on life.

PW&B’s Bridge No. 1 as seen today from the Grays Ferry bridge; Credit: Mick Ricereto 2016

Philadelphia – a former industrial powerhouse and erstwhile “workshop of the world” – is covered with train tracks both active and abandoned, with bridges crossing every small and large piece of water in the region. Rail travel was an important technology in the 19th century, allowing factories and communities all across the continent to be efficiently linked, growing our Victorian society exponentially in a matter of decades.

Down at the Schuylkill Crescent, the PW&B’s 1902 swingspan replaced the first permanent crossing, an 1838 multi-modal bridge called the Newkirk Viaduct. When the city of Philadelphia built the adjacent Grays Ferry road bridge in 1901, the railroad was free to remove the obsolete wooden bridge and build a modern steel span.

The Schuylkill was all that stood between Philadelphia and the early railroads linking points south – a mere 800 foot river crossing but a challenge nonetheless. For trains going north of Philadelphia, the southernmost crossing was at Trenton, where tidewater abruptly stops to meet the 8 foot Falls of the Delaware. The first rail bridge across the Delaware river was here in 1802. Interestingly this bridge evolved over the years to become today’s Trenton Makes steel truss which was completed in 1928.

Bridge builders eyeing points south of Trenton were presented a far-mightier challenge due to the river’s extreme width, tidal action and soft river bottom. It would be another 94 years before the first Philadelphia crossing was completed – Pennsylvania Railroad’s massive 4-span Petit truss Pennsylvania & New Jersey Railroad Bridge, known colloquially as the Delair Bridge.

The Delair Bridge from PA Side c1990; Credit: LOC.gov

Located just south of the Frankford creek in the Bridesburg section of Philadelphia and spanning to the Pennsauken, NJ area known as Delair, this massive structure was needed as much for freight and rail commerce as it was for holiday-making down the shore. To know the history of the Delair Bridge we must also examine Philly’s summertime quest with reaching the NJ coast and Atlantic City in particular.

Philadelphia’s Summer Getaway

America’s first premier holiday destination was Cape May, NJ. Long before rail travel, vacationers could sail down the Delaware on special excursion vessels and disembark on the bay side of the peninsula, often taking extended stays away from the frenzy of 18th century city life. Catering to the more well heeled looking for nature, fishing and fresh air, Cape May was also known to entertain many of our Presidents for a summertime stay at the beach.

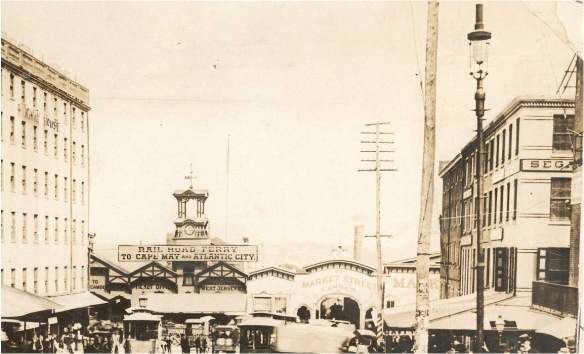

A voyager could also travel to NJ by Ferry directly from Philadelphia due east to Camden, and make the trip by carriage. A phalanx of ferry companies had traversed the waters between Philadelphia and Camden dating all the way back to 1688. The ferries welcomed passenger traffic as well as a huge trade in produce and livestock transport needed to feed America’s biggest city. In the 18th and early 19th century, a coach ride from Camden to the shore would be a dusty, bumpy affair and could take as many as 4 hours.

Market Street Ferry Terminal c.1896; Credit: Phila. Free Library)

In the early 1800s southern NJ was still completely wild, with the beach areas being a proverbial barren desert. After a visit to the almost-vacant Absecon Island an enterprising medical doctor by the name of Jonathan Pitney envisioned opportunity in getting Philadelphians out to the shore in by creating a new resort town expressly for taking in the healthy sea air. Pitney realized only a railroad could get people across the pine desert of southern NJ in a quick and efficient manner. Pitney partnered with entrepreneur Samuel Richards to build a new railroad from the Camden waterfront directly to the shore, convincing factory owners along the route that rail travel would help their businesses grow. Most of the investors thought the idea to build a health resort at the ocean end of the line was pure folly, but invested only for the important rail connection to the city and their core markets. Pitney and Richards raised enough capital to buy property all the way through from Camden to the coast and also purchase the entire island from early settlers. The partners began their plans for the new resort; Atlantic City was incorporated on May 1, 1854 with the first cross-state trip of the Camden & Atlantic City Railroad on July 1 of that year. The first train was a rustic open car rattletrap, but the adventure still attracted 600 hand-picked passengers for the maiden voyage.

Growth of the new town was swift; Pitney and Richards were smart to subsequently build an enormous hotel on the beach, quickly realizing that working-class folk would benefit the most by taking short stays or even day trips from the city. By 1874 500,000 Philadelphians made it to the shore during the summer season, prompting a second railroad to be added in 1877. The Philadelphia-Atlantic City Railway Co. undercut the Camden & AC substantially, with a one-way “excursion” ticket for $1. Inexpensive hotels and boarding housed popped up all along the newly-laid Atlantic City street grid. A working-class man could now afford a week at the shore with his family; the Jersey Shore was born.

The competing West Jersey Railroad completed their line to Cape May in 1863 but by then it was clear; Atlantic City had become America’s playground. The permanent boardwalk was added in 1896. The year-round population of Atlantic City was only 2000 in 1875; by 1900 it had swelled to 30,000. The more distant Cape May would be frozen as a charming but sleepy Victorian outpost.

A Quicker Way to the Shore

The mighty Pennsylvania Railroad wanted a piece of the Atlantic City action. The largest railroad in the world – in fact the largest corporation in the world at the end of the 19th century – went on a buying spree. Pitney and Richard’s original railroad and many smaller railroads throughout western NJ were purchased and absorbed into the PRR subsidiary West Jersey & Seashore RR (WJ&S) in 1896. Competition was very strong with 4 railroad companies crisscrossing the Delaware, ferry boats heaving the shallow tidewater into Camden’s piers many times daily. The Penn wanted desperately to create an advantage and decided to build a bridge across the Delaware. The tracks would need to skirt around the city’s Northeast industrial web but a direct route from center city’s Broad Street Terminal (the world’s largest train station) and across the river would still be more convenient than making the ferry trip to Camden.

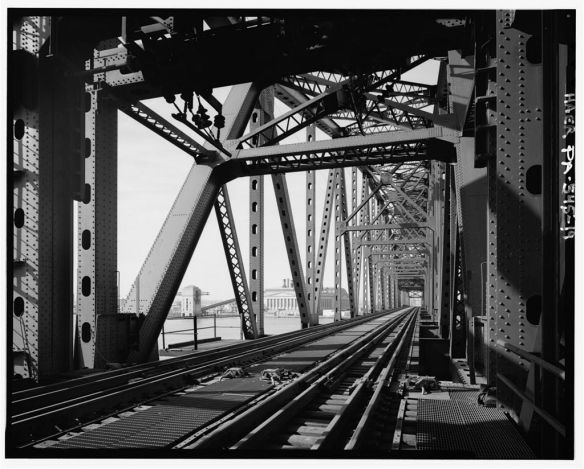

Inside truss detail looking west towards the Richmond Electric Station, c1990; Credit: LOC.gov

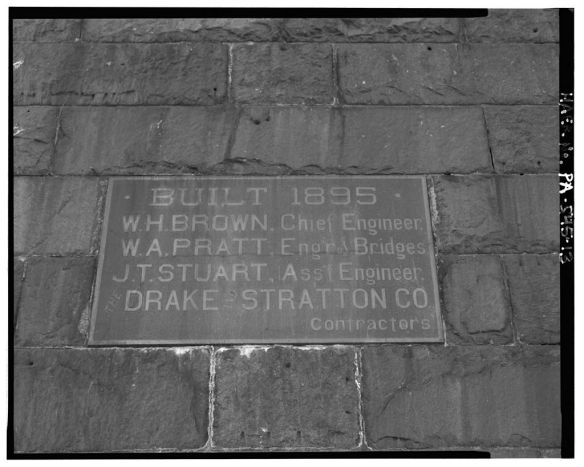

Crossing the Delaware required a movable span to allow for marine traffic, as building a bridge high enough for ocean-going vessels would be too costly. PRR head engineer William H. Brown called for a 323’ swingspan at the shipping channel, connected with 3 sections of massive 533’ Petit truss spans – 1 on the NJ side and two on the Pennsylvania. The Delair trusses would be very large and heavy, but still fall short of the longest truss spans by a mere 9 feet. The swing span was operated by steam and held the record for the longest center bearing pivot bridge in the world. Including the trestle approaches on both sides, total length of the structure is 4396 feet. Compare this with the later Ben Franklin bridge at 9573’, much longer due to the gradual climb needed to make 135’ shipping clearance.

The Delair Bridge today from Pennsauken, NJ with Richmond Electric Station and a distant center city in view; Credit: Mick Ricereto 2016

Work began with pier excavation on January 15, 1895. The steel work was started on November 1 of that year, and was finished in only 4 months. The massive trusses were fabricated with manganese steel milled by the Pencoyd Iron Works, the first large bridge to use the new high-tensile material. Pencoyd was located in Lower Merion Township directly across the Schuylkill from Manayunk. Interestingly, the hidden Pencoyd site is currently being redeveloped and the small rail bridge connecting to the site to the city – known as the Pencoyd Bridge – was recently restored as a car and pedestrian crossing.

The original builder’s plaque located on pier 6; Credit: LOC.gov

Throughout the first 30 years of use the Delair was busy with passenger traffic as Atlantic City entered it’s busy “Boardwalk Empire” period, with more and more weary city dwellers making the <90 minute trip from Broad Street for a week’s or even an afternoon’s promise of surf, sun and sin. Even after prohibition in 1920 – or perhaps even more so – Atlantic City was a place of escape due to it’s relaxed rules on booze and other illicit activities. As Nelson Johnson writes in his book Boardwalk Empire; The Birth, High Times and Corruption of Atlantic City “… it was a place where visitors came knowing the rules at home didn’t apply. The city flourished because it gave its guests what they wanted – a naughty good time at an affordable price”. The railroads too were booming, right up until the day the new Delaware Bridge (today named Ben Franklin) opened on July 1, 1926. With Philadelphia’s blue collar workers now wealthy enough to own personal cars and the advantage of cheap bus fares via the bridge, the railroads began to immediately suffer. By 1928, the WJ&S was down $2 million in revenue compared to just two years prior.

Mid Century Modification

In the 1950’s post-war boom years, America had an immense appetite for steel as buildings and projects such as the Interstate Highway System created a huge demand for materials. Responding to eastern demand, United States Steel started construction on the Fairless Hills steel plant on the upper tidal Delaware in the late 1940s. To serve this upcoming business, the Army Corps of Engineers decided to upgrade the river’s shipping capacity by straightening and dredging a deeper channel, while also requiring 500’ wide bridge clearance for more modern ships. Suddenly the Delair’s old pivot bridge was obsolete, with clearance not even half the new requirement.

The railroad’s engineers responded by permanently closing the old swing span and converting one of the original Petit trusses to a 542’ riveted Warren truss vertical lift span which would raise up for boat traffic to a height of 135’, equal to the Ben Franklin bridge. This engineering feat would require removing the original truss, building new piers and lift towers and installing the new pre-fabricated moving section quickly so as not to upset rail traffic for an unreasonable period.

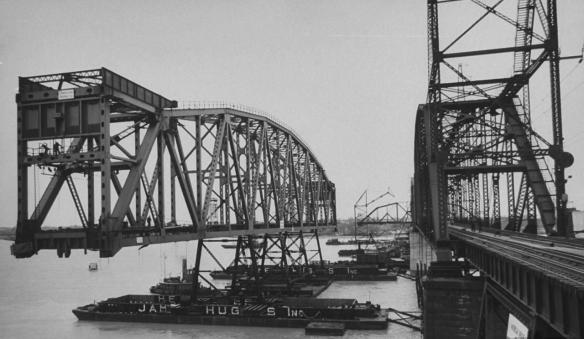

The new vertical lift span is floated into place in 1960; Credit: Creative Commons (photographer unknown)

Work began on March 1, 1960. The engineering concern Hardesty & Hanover, known for their work with railroad lift spans, was hired to complete the job. While sections of the bridge were being dismantled, the new span and towers were being constructed upriver and brought to the site on barges. The old span was removed by floating a barge underneath at low tide and lifting it away 6 hours later, while the new span was put in place similarly by lowering it at high tide and letting the barge float away as the river level went down.

The new lift towers needed huge piers to hold both the weight of trains, the bridge span itself and it’s equal weight in cable-actuated counterweights. The westernmost span needed to be shortened by 100’ to make room for the towers. The result is the unique, asymmetrical look of 4 different trusses.

The Delair Bridge during construction of the piers in 1960. The lift towers not yet built, note the shortened original western span; Credit: Creative Commons (photographer unknown)

When completed, the upgraded structure captured the record for longest double track vertical lift span in the US, falling short of the longest single track lift by only two feet (the Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridge, built in 1933).

The Delair Bridge Today

The Delair remains a busy rail bridge today; Credit: Mick Ricereto 2016

Today the bridge is used for CSX and Norfolk Southern rail transportation as well as NJ Transit’s Atlantic City line. The bridge was modernized heavily in 2012 with an $18.5 million TIGER grant, bringing the structure safely into the 21st century.

Curiously the Delair is mostly hidden from our daily lives. Seen briefly from I-95 – near appropriately, the Bridge Street exit – the lift span towers look dark and menacing in the shadows of the Betsy Ross. From the south the Richmond Electric Station and Tioga Marine Terminal blocks the shoreline for miles. The best viewing is from the Jersey side as the bridge is located at the end of the road with a small parking lot for a boat launch ramp and tiny fishing pier.

Detail view of the Delair swing span; Credit – Mick Ricereto 2016

Taking NJT’s Atlantic City line out of 30th Street Station is a fabulous way to experience the bridge. The right-of-way takes an alternate route through the industrial northeast of the city, into Frankford Junction and over the Delaware. For a transit-filled afternoon, take the NJT from 30th Street, stop and view the bridge from water’s edge at Pennsauken station and then walk back up the hill for the River Line back to Camden. From here walk over the Ben Franklin or take PATCO back over and connect to anywhere in the city.

How long was the bridge closed for the work to install the vertical lift and what did the PRR do with the traffic that used it?

Hi Joe – thanks for commenting. I didn’t fully articulate the 1958-60 lift span redesign/installation but it went like this: the lift span was assembled on barges upstream on the PA side. In the meanwhile, pier 2A was inserted in place under the existing middle span. This way they could shorten this truss without disrupting rail traffic too much. When the new lift span was ready they moved it over and made the swap with the tides. The lift towers were then built and everything linked up for vertical action (note: the swing span was still functioning for marine traffic this whole transition period). So, from what I can ascertain, rail traffic was only disrupted on a day-to-day basis! (this comment may be doubled up as I wrote the whole thing and then WP made it disappear … maybe. Mod later).