Cultural Resistance in the Costa Rican Caribbean

Music and Ethnicity

Sitting in the restaurant of the Park Hotel in Port Limón, I began to reminisce about the years I’ve spent visiting, learning about and studying the culture and people of the Caribbean province of Costa Rica. Images come to mind from decades ago, when with naive curiosity I began to travel to the port of Limón and to the small southern coastal towns such as Cahuita, Old Harbour and Manzanillo, in the Talamanca region.

At that time, I was not aware of the antagonistic realities that the world’s cultures face with the omnipresent Western culture and its characteristic symptom: Eurocentrism.

When I watched Papa Tun sing his simple calypsos in exchange for a plate of food, the only thing I saw was an almost destitute folk singer who clung to his musical traditions inherited from his African ancestors colonized by the British.

As the years went by, I got to know better those singers called calypsonians who told everyday stories and who in some way wove a collective texture that told the story of their Afro-Caribbean origin and their permanent struggle to be respected as human beings and as citizens of Costa Rica. I heard how the country received them coming with indifference, but had to accept their arrival due to the imperative need to have that workforce, to build the railway to the Caribbean that would allow the ruling class to amass original capital on which to develop the small country based on its desire for wealth.

While current globalization, with all its technological resources, allows itself to shorten distances and extend Western culture immediately in almost every corner of the planet, popular culture, an expression of the marginalized sectors, unintentionally confronts that technological-cultural onslaught daily,, simply by practicing and renewing the patterns of social behavior and their ancestral cultural expressions, in song, dance, cooking, spirituality and other ways in which diverse cultures live and feel life in this world

Limón calypso thus has been a bastion of cultural resistance in the Caribbean province of Limón in Costa Rica. The Limon calypso, a hybridization between the Jamaican mento (which influenced ska and reggae) and the Trinidad calypso, takes particular and unique forms, in the amalgam of migratory flows, cultural exchanges and coexistence with different ethnic groups such as the ancestral Bribris and Cabécares, the Chinese, the Culies (emigrants from India) and the Hispanic Creole population.

During the years following the migration of Black workers in the 1870s to build the railroad to the Caribbean, and later as workers in the banana industry, the province of Limón functioned, to a large extent, as a territory within an enclave economy, where the United Fruit Company (UFCO) managed most of the activities. The government presence was minimal and, in many cases, symbolic.

After the transfer of the UFCO to the Pacific region, Limón was left adrift, and it was then that the government of the republic was forced to intervene in that forgotten province handed over to foreign companies, first to the railway company, and later to the enclave economy administered by the UFCO.

The virulent persecution against the Afro-descendant population and its cultural expressions has no parallel in the history of Costa Rica.

During the 1940s, when the Government entered the province of Limón, which had been practically adrift after the transfer of the UFCO to the Pacific area, it proposed to impose the official culture without giving the Black population room to negotiate or to seek a balanced alternative that would allow them to maintain their population’s original culture, including Caribbean English, the language of their island ancestors.

Prominent figures of the dominant culture, such as Clorito Picado, León Cortés and Carlos Monge Alfaro, issued deeply racist statements that supported the violent actions and violations of human rights that occurred in Limón in the 1940s. Monge Alfaro’s opinion about Afrodescendants, becomes a good an example, in a 1943 publication of Social and Human Geography of Costa Rica, in which he argues that Blacks in Costa Rica are “pedantic and stupid” (Harpelle N. Ronald (1994) The West Indians of Costa Rica. McGill-Queen’s University Press Canada: 129.)

Let go hand me, Lord!

let go me hand

I am a true born Costa Rican.

I am a true born Costa Rican.

I was born in Puerto Limón

eating rondon and callaloo

I am a true born Costa Rican.

This song by the calypsonian Charro Limonense expresses that discomfort regarding aggression,

intervention and the constant need to prove one’s nationality:

Let go me hand,

let go me hand

I am a true born Costa Rican

And on the other hand, the roots in his Afrodescendant identity:

I was born in Puerto Limón

Eating calalú and rondón

Different cultural expressions were persecuted, such as the Pocomía ritual, about which multiple rumors and stories were created that spread fear in the population. Under the cover of this campaign of fear, religious leaders such as Altiman Dabney were deported, and many of their followers were deported or arrested on simple suspicion of practicing the ritual.

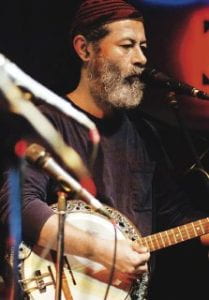

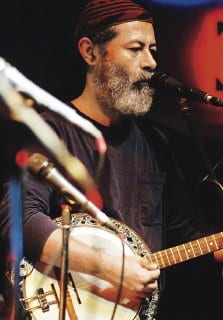

Photo: Adriana Ovares

The relationship between religious practices of African influence in Limón and music can be illustrated by the following quote from Carmen Murillo, which refers to the end of the 19th century, and allows us to glimpse the Afro-Caribbean musical practices transferred to our Limón coast from different island points of the Caribbean. In the style of the musical processes that occurred in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Haiti, Jamaica or Trinidad, the use of drums and wooden boxes in Limón shows the presence of Afro-Antillean musical forms, from the early process of settlement of the Black population in this zone. The quote also alludes to activities such as singing to the dead, a typical characteristic of the Yoruba worldview expressed in the cult of spirits and ancestors:

“With a marked Caribbean accent, the days and nights in the port pass between gatherings in the corridors, food sales in the streets, songs to the dead, billiards and a large number of liquor stores where, unlike the rest of the country, they dance daily to the sound of drums and cajones, until the early hours of the morning” (Murillo, Carmen (1995). Identities of Iron and Smoke. Saint Joseph. Porvenir Editorial.: 54).

The songs, dances and drums or cajons are associated in the musical history of the Caribbean with the ancestral religious practices coming from Africa, mainly those of Yoruba origin. The visceral persecution and disappearance of Pocomia practices in Limón possibly cut off an important vein of artistic expressions linked to Afro-Caribbean religious practices.

Harpelle says in his 1994 book, “As soon as Cortés assumed the presidency in 1936, his government began issuing orders that amounted to assaults the West Indian minority.” That is to say, as soon as León Cortés assumed the presidency in 1936, his government began to issue orders that promoted attacks on the Black ethnic group in Limón, making it clear that the repudiation of this population had official status.

Despite the cultural impositions and human rights violations that occurred in Limón in the 1940s, Black residents continued their cultural practices against the official homogenizing, the vertical view of non-white human groups and Eurocentric current. The use of Caribbean English achieved continuity thanks to the English schools maintained and financed by the communities, who refused to give up the language of their grandparents. In this sense, furthermore, calypso has played a leading role in maintaining the link between the population and Creole English. Most calypsos are sung in English, and they spread ways of thinking and cultural practices of the Afro-Caribbean population that settled in Limón since the end of the 19th century.

The claim of the right to Costa Rican nationality and its cultural traits has meaning when it comes to a population whose cultural profile contrasts diametrically with the ideal of a nation built by the ruling class, an invention that excludes non-white populations, religions other than Catholicism. and languages other than Spanish.

The Afro-Caribbean descendant population that arrived in Limón contradicted in its cultural and phenotypic traits all that idyllic invention of the coffee oligarchy of the late 19th century.

The absence of civil and citizen rights necessarily involved Blackness as a concrete fact. It was not a simple reaction of ostracism before a group of foreigners settled in national territory, it was the rejection of a threatening ethnic group that contained meanings and signifiers that contradicted the artificially constructed ideal of the nation.

The invisibility of Indigenous people and other mixed groups, emerging from the colonial period, placed this new migration of Black settlers as a real threat, as it was going to obscure the artificial myth of whiteness.

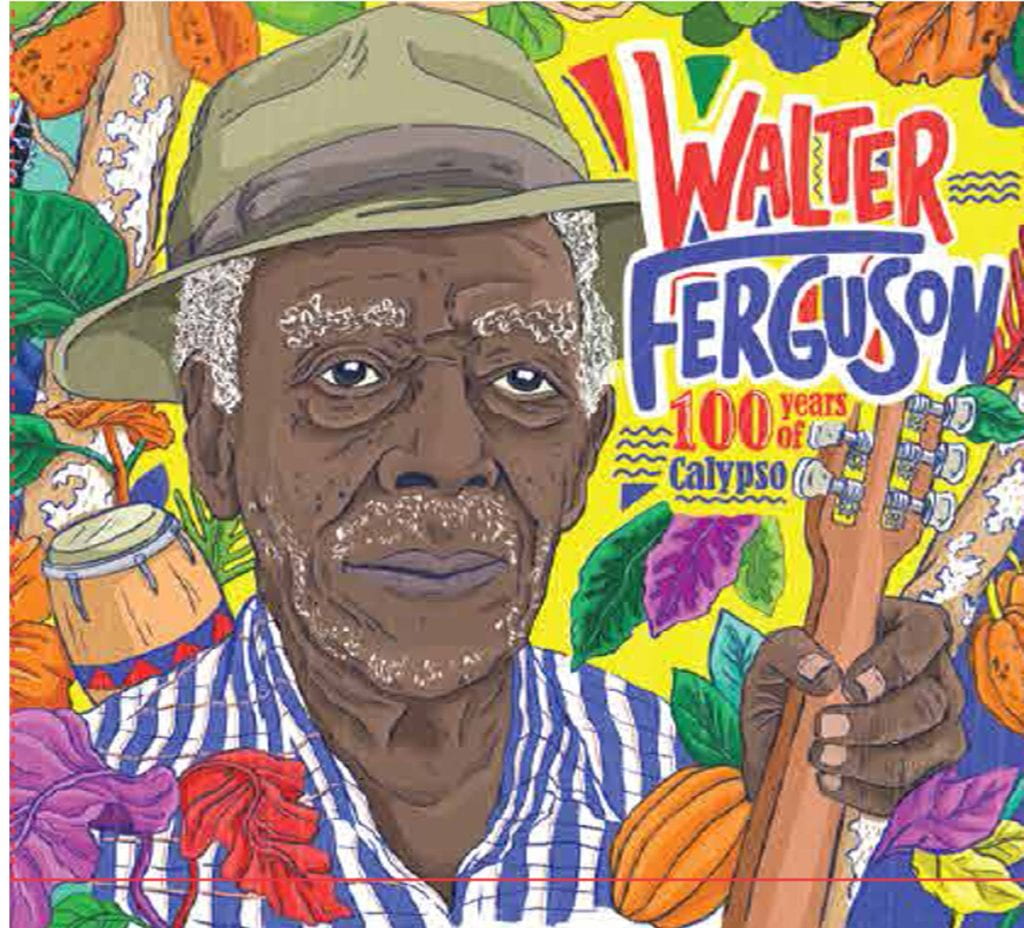

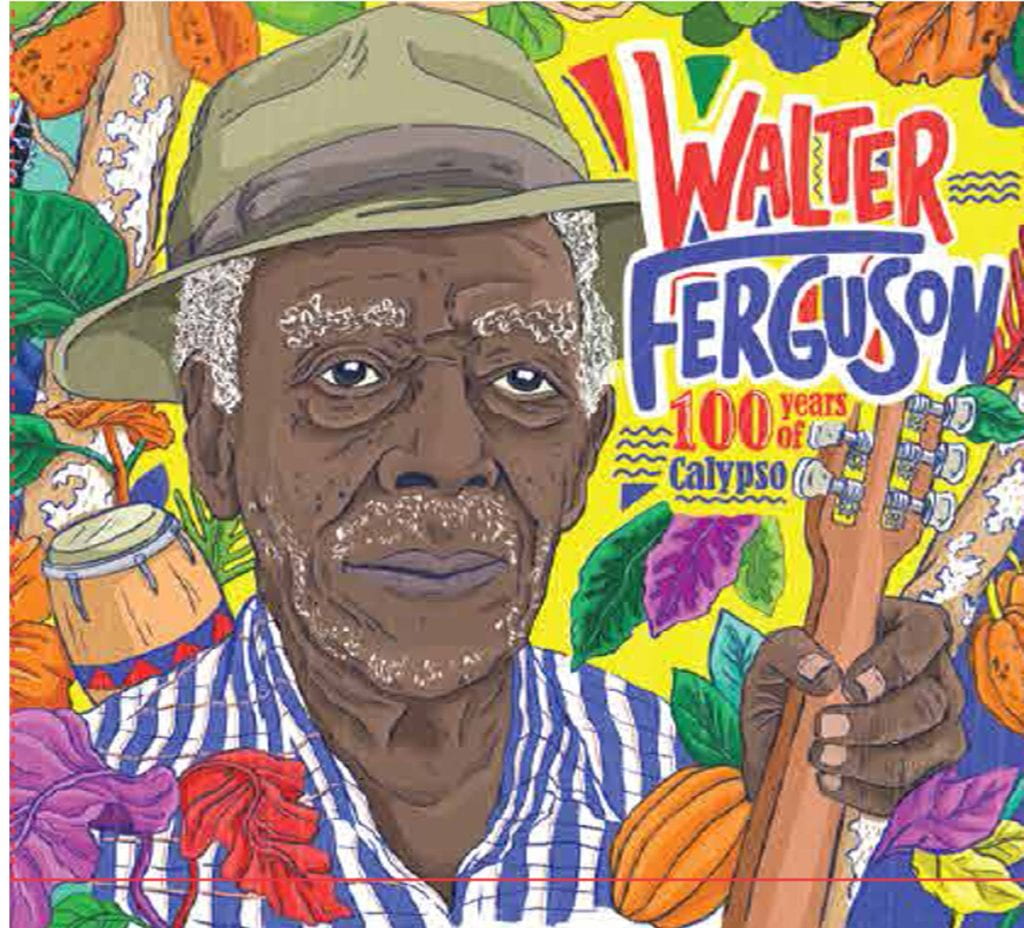

The possible contradictions that the Afro population faced in Limón in the 1930s and 1940s, regarding whether to continue living in Costa Rica or return to their countries of origin, could be illustrated with this stanza from a calypso by composer Walter Ferguson, who lived through those years and witnessed the uncertainty aroused by the intervention of the government and the “white” population:

Better send me back to my country,

Send my back to my country,

Send me back to my native land,

Me neighbor want to kill me

That is the thing I can’t understand

The allusions to identities and origins are reflected in calypsos such as the following, also composed by Walter Ferguson:

My great grandmother was an Anglican

My great grandfather from Africa

My cousin was a musician

That’s how I became a calypsonian

My uncle was a Baker, died in Jamaica

Had two daughters, name Brown Paper

Thin like a wafer, sharp like a razor

African and colonial origins emerge in the lyrics of this calypso. Here the author seems to strengthen their identities through allusions to their ancestors (“my Anglican great-grandmother,” due to English colonialism, and “my African great-grandfather”, due to slavery), their origins, their occupations, as well as their qualities. physical and mental.

Allusions to specific elements of African culture are also part of the discourse of Limonense calypso. The case of Anansy and Tacuma, characters from the stories that went from West Africa to the Caribbean, included in the lyrics of this calypso by Ferguson, illustrate the previous statement:

I was invited to a party

I was glad for the festival

it was tacuma and anansi

you must imagine

how the people were liberal

The defense of Blackness as a legitimate element in the Costa Rican context necessarily leads to the fight for citizen rights and ultimately to obtaining nationality, that struggle, in its deepest sense, is the eternal confrontation between cultures threatened by omnipresent domination of the Eurocentric cultural approach, exercised both from the centers of world power and from the peripheral countries that assumed domination from the colonization processes.

Limón calypso is a bastion of unwavering struggle for the preservation of Afro-Caribbean culture and heritage in the province of Limón, in a Costa Rican historical context plagued by segregation, invisibilization, persecution and overt and latent racism.

Manuel Monestel is a Costa Rican musician, sociologist and ethnomusicologist. The founder and lead singer of Cantoamérica, he is the author of Ritmo, Canción e Identidad: El Calypso Limonense (Editorial de la Universidad Estatal a Distancia, 2005) and Enclave Afro Caribe(Centro Cultural de España, 2010). He was a 2008-09 Society for the Humanities Visiting Fellow at Cornell University.

Resistencia Cultural en el Caribe Costarricense

Música y Etnicidad

Por Manuel Monestel

Sentado en el restaurante del Park Hotel en Puerto Limón, comencé a divagar sobre el tiempo que he pasado visitando, conociendo y estudiando la cultura y la gente de la provincia caribeña de Costa Rica. Vienen a mi mente imágenes de décadas atrás, cuando con curiosidad ingenua comencé a viajar al puerto de Limón y a los pueblitos costeros sureños como Cahuita, Puerto Viejo y Manzanillo ubicados en la región de Talamanca.

En aquel tiempo, yo no estaba consciente de las antagónicas realidades que enfrentan las culturas del mundo con la omnipresente cultura occidental y su síntoma característico: el eurocentrismo.

Cuando yo miraba a Papa Tun cantar sus sencillos calipsos a cambio de un plato de comida, lo único que yo veía era un cantor popular, casi indigente que se aferraba a sus costumbres musicales heredadas de sus ancestros africanos colonizados por Gran Bretaña.

Con el paso de los años conocí mejor a aquellos cantores llamados calypsonians que narraban historias cotidianas y que de alguna manera tejían una textura colectiva que narraba la historia de su origen afrocaribeño y su lucha permanente por ser respetados como seres humanos y como ciudadanos de este país. Me percaté de cómo Costa Rica los vio venir con desidia y que tuvo que aceptarlos por la necesidad imperiosa de contar con aquella mano de obra, para construir el ferrocarril al Caribe que permitiría a la clase dominante amasar un capital originario sobre el cual desarrollar el pequeño país en función de sus ansias de riqueza.

Mientras la globalización actual , con todos sus recursos tecnológicos, se permite acortar distancias y sembrar la cultura occidental de manera inmediata en casi cada rincón del planeta, la cultura popular, expresión de los sectores marginales, confronta sin proponérselo, de manera cotidiana, aquel embate cultural tecnológico, simplemente practicando y remozando las pautas de comportamiento social y sus expresiones culturales ancestrales, en el canto, la danza, la culinaria, la espiritualidad y demás formas en que las culturas diversas viven y sienten la vida en este mundo.

Entonces, el calypso limonense ha sido un bastión de resistencia cultural en la provincia caribeña de Limón en Costa Rica. Es una hibridación entre el mento de Jamaica (una influencia del reggae y del ska) y el calypso de Trinidad, toma formas particulares y únicas, al calor de los flujos migratorios, los intercambios culturales y la coexistencia con distintos grupos étnicos como las ancestrales bribris y cabécares, los chinos, los culíes (emigrados de la India) y la población hispánica criolla.

Durante los años subsiguientes a las migraciones de trabajadores negros de la década de 1870 para construir el ferrocarril al Caribe, y luego como mano de obra de la industria del banano, la provincia de Limón funcionó, en buena medida, como un territorio dentro de una economía de enclave, donde la United Fruit Company (UFCO), administraba la mayoría de las actividades. La presencia del gobierno era mínima y en muchos casos simbólica.

A partir del traslado de la UFCO a la región del Pacífico, Limón quedó a la deriva, y es entonces cuando el gobierno de la república se ve obligado a intervenir aquella provincia olvidada y entregada a las compañías extranjeras, a la ferrocarrilera primero, y posteriormente a la economía de enclave administrada por la UFCO.

La persecución virulenta contra la población afrodescendiente y sus expresiones culturales no tiene parangón en la historia de Costa Rica.

Durante la década de 1940, cuando el Gobierno entró en la provincia de Limón, que había quedado prácticamente a la deriva después del traslado de la UFCO a la zona del Pacífico, se propuso imponer la cultura oficial sin dar espacio a la población negra de negociar o de buscar una alternativa equilibrada que permitiera mantener la cultura original de su población, incluyendo el inglés caribeño, lengua de sus ancestros insulares.

Prominentes figuras de la cultura dominante como Clorito Picado, León Cortés y Carlos Monge Alfaro, emitieron declaraciones profundamente racistas que sustentaron las acciones violentas y violatorias de los derechos humanos que ocurrieron en el Limón de los años ‘40. Como ejemplo funciona la opinión de Monge Alfaro sobre los afrodescendientes, en una publicación de Geografía Social y Humana de Costa Rica de 1943 , en la cual argumenta que los negros en Costa Rica son “pedantes y estúpidos” (Harpelle N. Ronald (1994) The West Indians of Costa Rica. McGill-Queen´s University Press Canada).

Let go me hand, Lord!

let go me hand

I am a true born Costa Rican.

I am a true born Costa Rican.

I was born in Puerto Limón

eating rondon and callaloo

I am a true born Costa Rican.

Esta canción del calypsonian Charro Limonense, expresa ese malestar con respecto a la agresión, a la intervención y a la necesidad constante de demostrar su nacionalidad :

Déjeme en paz,

Suélteme el brazo

Yo soy un costarricense nacido aquí

Y por otra parte el arraigo a su identidad afrodescendiente:

Nací en Puerto Limón

Comiendo calalú y rondón

Diferentes expresiones culturales fueron perseguidas, como es el caso del ritual Pocomía, sobre el cual se crearon múltiples rumores e historias que sembraban el miedo en la población. Al amparo de esa campaña del miedo, se deportaron dirigentes religiosos como Altiman Dabney, y muchos de sus seguidores fueron deportados o arrestados por simple sospecha de practicarla.

Photo: Adriana Ovares

La relación de las prácticas religiosas de influencia africana en Limón y la música puede ser ilustrada por la siguiente cita de Carmen Murillo, la cual remite a finales del siglo XIX, y permite asomarse a las prácticas musicales afrocaribeñas trasladadas a nuestra costa limonense desde distintos puntos insulares del Caribe. Al estilo de los procesos musicales que se dieron en Cuba, Puerto Rico, Haití, Jamaica o Trinidad, el uso de tambores y cajones de madera en Limón muestra la presencia de las formas musicales afroantillanas, desde el proceso de asentamiento de la población negra en esa zona. La cita alude, además, a actividades como el canto a los muertos, típica característica de la cosmovisión yoruba expresada en el culto a los espíritus y a los ancestros:

Con un marcado acento caribeño, los días y las noches en el puerto transcurren entre tertulias en los corredores, ventas de comida en las calles, cantos a los muertos, billares y una gran cantidad de expendios de licores donde, a diferencia del resto del país, a diario se baila al son de tambores y cajones, hasta altas horas de la madrugada (Murillo, Carmen (1995). Identidades de Hierro y Humo. San José. Editorial Porvenir: 54).

Las canciones, las danzas y los tambores o cajones, se asocian en la historia musical del Caribe a las ancestrales prácticas religiosas venidas de Africa, principalmente las de origen yoruba. La persecución visceral y la desaparición de las prácticas de Pocomía en Limón posiblemente cercenó una veta importante de expresiones artísticas ligadas a las prácticas religiosas afrocaribeñas.

Dice Harpelle Ronald, “As soon as Cortés assumed the presidency in 1936, his government began issuing orders that amounted to assaults the West Indian minority.” (Harpelle, 1994: 103). Es decir que, tan pronto como León Cortés asumió la presidencia en 1936, su gobierno comenzó a emitir órdenes que promovieron ataques a la etnia negra en Limón, dejando en claro que el repudio a esta población tenía rango oficial.

A pesar de las imposiciones culturales y las violaciones a los derechos humanos ocurridas en el Limón de los años ‘40, la población negra continuó sus prácticas culturales contra la corriente oficial homogeneizante, verticalista y eurocéntrica. El uso del inglés caribeño logró continuidad gracias a las escuelas de inglés mantenidas y financiadas por las comunidades, que se negaban a renunciar a la lengua de sus abuelos. En este sentido, además, el calypso ha jugado un papel protagónico manteniendo el nexo entre la población y el Creole English. La inmensa mayoría de calipsos se cantan en inglés, y difunden maneras de pensar y prácticas culturales de la población afro caribeña que se estableció en Limón desde finales del siglo XIX.

La reivindicación del derecho a la nacionalidad costarricense y a sus rasgos culturales, tienen significado cuando se trata de una población cuyo perfil cultural contrasta diametralmente con el ideal de nación construido por la clase dominante, invención que excluye las poblaciones no blancas, las religiones distintas al catolicismo y las lenguas diferentes al español.

La población afrodescendiente caribeña que llegó a Limón contradecía en sus rasgos culturales y fenotípicos toda aquella invención idílica de la oligarquía cafetalera de finales del siglo XIX.

La ausencia de derechos civiles y ciudadanos pasaba necesariamente por la negritud como hecho concreto. No se trataba de una simple reacción de ostracismo ante un grupo de extranjeros instalados en territorio nacional, se trataba del rechazo a una etnia amenazante que, contenía significados y significantes que contradecían el ideal de nación construido artificialmente

La invisibilización de los indígenas y de otros grupos mezclados, surgidos a partir del periodo colonial, colocaba a esta nueva migración de pobladores negros como una amenaza real, en tanto iba a oscurecer la blanquitud artificial que se enarbolaba como rasgo típico de la nación.

Las posibles contradicciones a las que se enfrentaba la población afro en el Limón de los años 1930 y 1940, sobre si seguir viviendo en Costa Rica o regresar a sus países de origen, podrían ilustrarse con esta estrofa de un calypso de Walter Ferguson, quien vivió esos años y fue testigo de la incertidumbre suscitada con la intervención del gobierno y de la población “blanca”:

Better send me back to my country,

Send my back to my country,

Send me back to my native land,

Me neighbour want to kill me

That is the thing I can’t understand

Las alusiones a identidades y orígenes se plasman en calypsos como el siguiente, también compuesto por Walter Ferguson:

My great grandmother was an anglican

My great grandfather from Africa

My cousin was a musician

That´s how I become a calypsonian

My uncle was a Baker, died in Jamaica

Had two daughters, name Brown Paper

Thin like a wafer, sharp like a razor

Los orígenes africanos y coloniales afloran en las letras de este calypso. Aquí el autor parece afianzar sus identidades por medio de alusiones a sus ancestros (“mi bisabuela anglicana”, por el colonialismo inglés, y “mi bisabuelo africano”, por la esclavitud), los orígenes de ellos, sus oficios, así como sus cualidades físicas y mentales.

Las alusiones a elementos específicos de la cultura africana también son parte del discurso del calypso limonense. El caso de Anansy y Tacuma, personajes de los cuentos que pasaron del Africa Occidental al Caribe, incluidos en la letra de este calypso de Ferguson, ilustran la afirmación anterior:

I was invited to a party

I was glad for the festival

it was tacuma and anansi

you must imagine

how the people was liberal

La defensa de la negritud como elemento legítimo en el contexto costarricense conlleva necesariamente a la lucha por los derechos ciudadanos y en última instancia a la obtención de la nacionalidad, esa lucha, en su sentido más profundo es la eterna lucha entre las culturas amenazadas por la omnipresente dominación del enfoque cultural eurocéntrico, ejercido tanto desde los centros de poder mundial, como desde los países periféricos que asumieron la dominación a partir de los procesos de colonización.

El calypso limonense es un bastión de lucha inclaudicable por la preservación de la cultura y la herencia afro caribeña en la provincia de Limón, en el contexto histórico costarricense plagado de segregación, invisibilización, persecución y racismo manifiesto y latente.

Manuel Monestel es músico, sociólogo y etnomusicólogo costarricense. Fundador y vocalista de Cantoamérica, es autor de Ritmo, Canción e Identidad: El Calypso Limonense (Editorial de la Universidad Estatal a Distancia, 2005) y Enclave Afro Caribe (Centro Cultural de España, 2010). Fue investigador visitante de la Society for the Humanities en 2008-09 en la Universidad de Cornell.

Related Articles

Homecoming and Public Education: The Cancel Culture (of class time) in Costa Rica

When I returned home on my sabbatical, I couldn’t stop thinking about Svetlana Boym’s extraordinary book, El futuro de la nostalgia.

Crisis of Citizen Insecurity in Costa Rica: A Challenge to the Model of Demilitarized Democracy

I began my political and public service career thirty years ago as Minister of Public Security, the first woman to ever hold that post in my country, Costa Rica.

Editor’s Letter: Is Costa Rica Different?

Is Costa Rica different?