Pagsanjan had everything a municipality could want to qualify as a key tourist attraction. It has the famous waterfalls and grand ancestral houses, a showcase of the town’s rich history and heritage.

Writer and publisher Gilda Cordero-Fernando has written an essay about her hometown describing Pagsanjan “was a town that had a passion for a comfortable and cultured life.”

She recalls a time when the Yangco Steamship Company ran boats from the Pagsanjan River to Laguna de Bay and then into the Pasig River. Passengers would disembark close to Escolta, the premier commercial street of Manila at the turn-of-the century. This easy access to Manila made Pagsanjan a trade center which raised the town to a position of superiority among it neighbors.

A few decades ago, Pagsanjan’s reputation and heritage were marred that of a modern- day Sodom. It took some dedicated effort from concerned residents and the local government to clear Pagsanjan’s name. Disco and beer joints were closed and the pedophiles informed that they were no longer welcome.

Although Pagsanjan has fallen on hard times, its passion for culture and comfort is still discernable as we drive into town beneath the two lions that stands on the Puerta Real over Calle Rizal, the town’s main road.

This stone gate was built to recall the legendary miracle attributed to the town’s patroness, Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe. The legend goes that in December 8, 1877 (feast of the Inmaculada Concepcion) a terrorostic group led by Tankad came to bring havoc to the town. It is said that the bandits were stopped at the site where the stone gate is erected upon seeing a luminous apparition of the beautiful lady holding a shining sword.

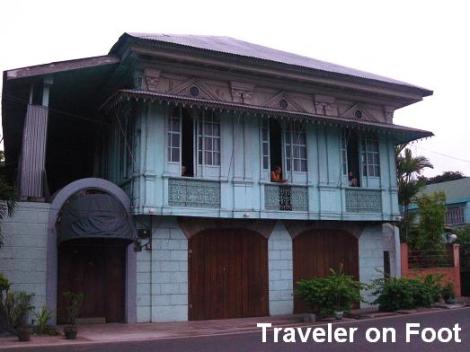

The houses along the main road still put up a façade of stateliness. The large elaborately carved windows and doors, the balconies, the gates, bespeak a place and time when the principalia rule their town.

Local architects, artist and designers are exerting a significant amout of effort in turning Pagsanjan into a living museum much like Intramuros or Vigan. They are aware that this effort will take time since they have to move carefully, using old photographs and reference books to ensure the accuracy of the restoration.

More to the problem of restoring Pagsanjan to its former glory is that the town was badly damaged during World War II. Pagsanjan was repeatedly carpet-bombed by Allied raids, destroying much of the rich architecture. Still, enough of the old homes remain.

Perhaps the grandest house in this town of grand houses is found at the end of the Calle Rizal –Pagsanjan Church. Founded in 1687 by Agustin de la Magdalena as a bamboo and nipa affair, the stone Spanish building was built in 1690.

Inside the church is a treasure trove of local religious art. A life-size Virgin Mary stands on a crescent made of carabao horn, the Santo Niño’s breached are tucked into silver cowboy boots, the Santo Intierro wears a richly embroidered salumbaba or death scarf.