Quirino at 125: A Statesman and Survivor

/Elpidio Quirino, 6th President of the Philippines (1948 - 1953) (Photo courtesy of the President Elpidio Quirino Foundation)

I don’t tell acquaintances or coworkers that in another country there are boulevards, buildings and an entire province that bear my last name. I’m no tropical Vanderbilt. In Apo Lakay by Carlos Quirino, the biography of Elpidio Quirino, the Philippines’ sixth president, describes the family as coming from humble origins.

“Lolo Elpidio” as he’s referred to in the family, seemed to share a kind of indifference to the class system. His progressive values were intertwined with a sort of folksy sense of humor that spoke to his middle class background. In terms that the embattled millennial can understand, he put himself through high school and university while working first as a barrio teacher and later in Manila as a portrait artist.

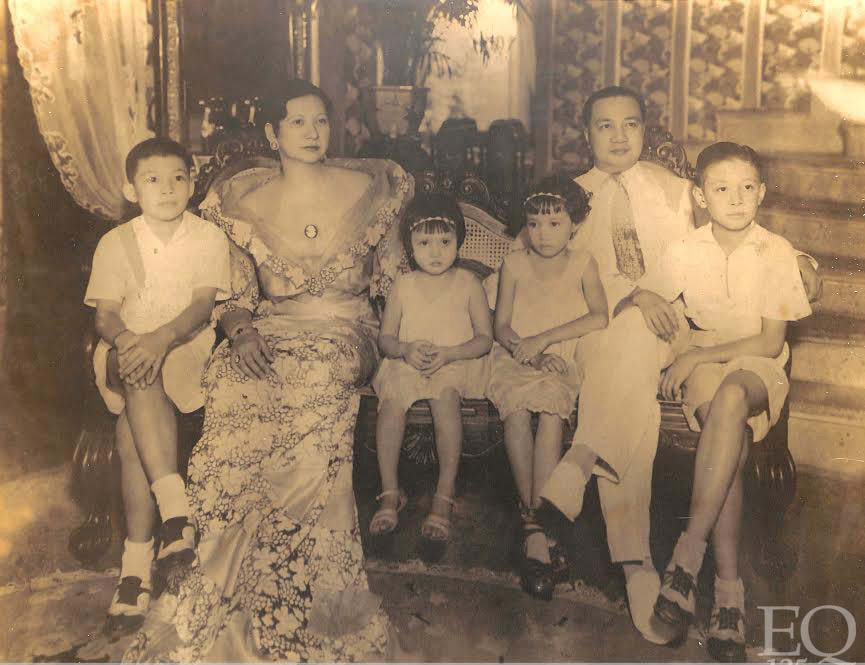

The last complete family photo of President Elpidio Quirino with wife Alicia Syquia and children. Doña Alicia and their 3 children Armando, Norma and Fe were killed by the Japanese during WWII. (Photo courtesy of the President Elpidio Quirino Foundation)

While I’m co-authoring and editing a book of inspirational quotes on Elpidio Quirino as a statesman and survivor, I’m learning more about the man than I ever did when I was 12 years old and writing a book report on a notable ancestor. At the time, much of his life’s nuances were probably lost on me. As an adult, it’s considerably much easier to contextualize the moral dilemmas he faced.

He was criticized for a perceived indifferent attitude later in his career exemplified by the almost comical 5,000 peso bed controversy. His opposition alleged that Elpidio Quirino obtained a P5,000 bed and lived in a state of nepotistic luxury at Malacañang. However, his daughter Vicky Quirino detailed in his memoirs, The Judgement of History, how the palace fell into disrepair and her father had actually used P5,000 to furnish the entire room including the infamous bed which was appraised by independent auditors at P300 in 1949.

What critics fail to realize is that Elpidio Quirino was a leader of a nation in ruins. In 1948, he needed to flex political muscles exhausted by World War II. The nation was caught at an increasingly defined crossroads between East and West.

Philippine President Elpidio Quirino with US President Harry Truman (Photo courtesy of the President Elpidio Quirino Foundation)

Elpidio Quirino was the leader of a war-torn nation, but he also exemplified Philippine ideals of forgiveness and compassion. He had been devastated by the war on a deeply personal level, witnessing the deaths of his wife, Alicia, and three children during the Battle of Manila in 1945.

In spite of this tragedy, Quirino later pardoned Japanese war criminals in July 1953. He granted executive clemency to 437 war criminals, 100 of whom were Japanese, while the rest were Filipinos accused of collaborating with Japanese occupiers. His compassion and foresight into modern diplomacy paved the way for normalized diplomatic relations with one of the Philippines’ most important modern-day allies.

Earlier this year, his granddaughter, Cory Quirino, said in an interview for The Japan Times, “He had moments in his life when Dad found him in the same kind of silence, sitting in one corner, very solitary, remembering the family…But not once did he say anything bad about the Japanese.”

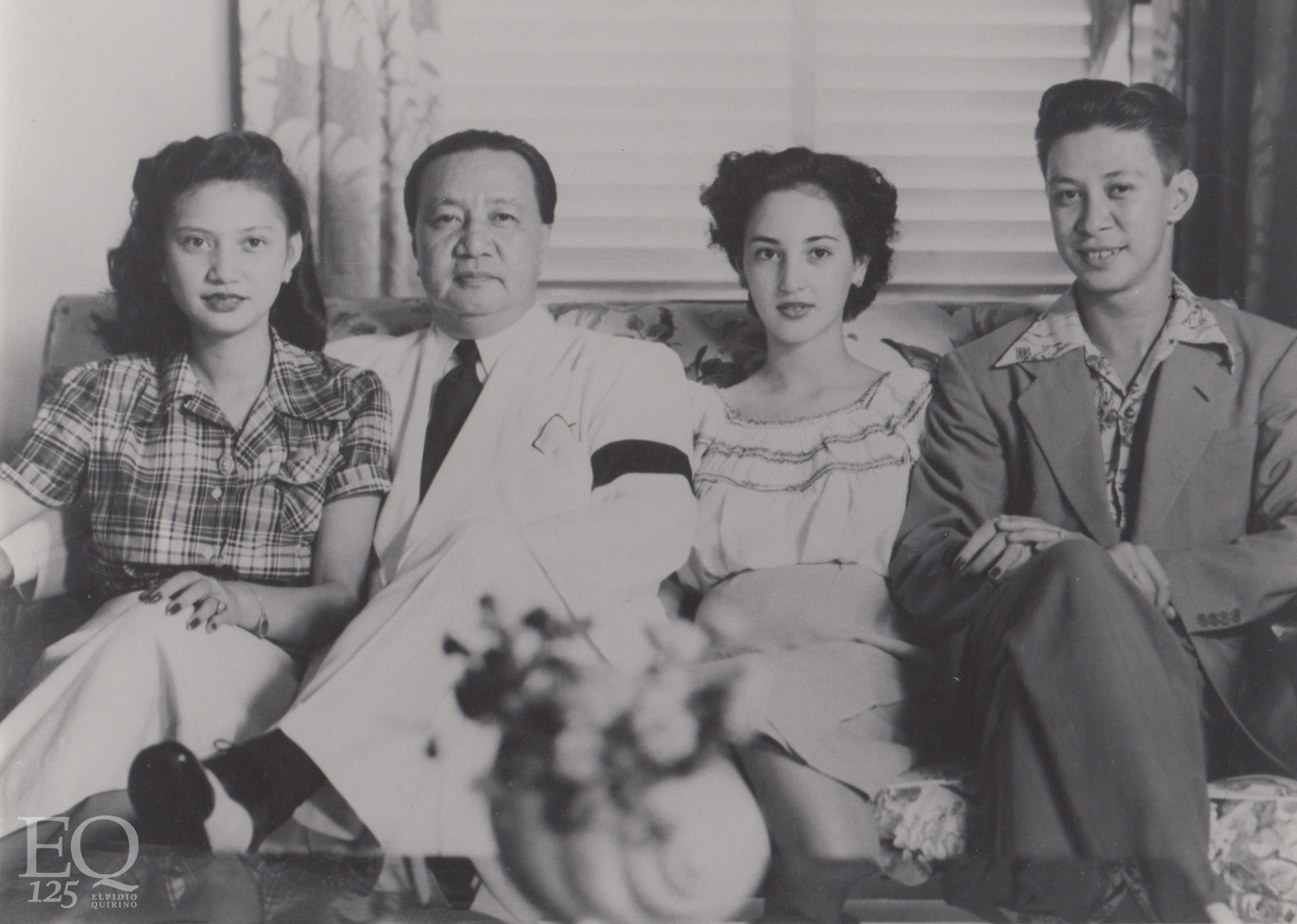

President Elpidio Quirino with his family in Malacañang: daughter Victoria Quirino-Delgado who acted as First Lady; son Tomas with wife Nena Rastrollo. (Photo courtesy of the President Elpidio Quirino Foundation)

The postwar era saw Quirino as the consummate diplomat, traveling to the United States and abroad. He put his best, well-heeled foot forward to be on par with President Harry Truman, Chiang Kai Shek and others who routinely used regional leaders like him as pawns in a high stakes chess match between Eastern communism and Western capitalism. His stolid determination to see his nation succeed surpassed his critics’ expectations, and he was even celebrated with a ticker tape parade in the U.S., a country that, just 30 years prior, saw the Philippines as a backward, uncivilized “little brown brother” unworthy of its own sovereignty.

At home, his ideals were put to the test. President Quirino advocated progressive reforms that mirrored Franklin D. Roosevelt’s modernizing efforts in the U.S. Quirino sought to make education the cornerstone of a brighter Filipino future.

Calling to mind his own experiences as a barrio teacher and later dean of Adamson University, he spoke before thousands of educators on June 5, 1951. The Quirino Way, a collection of his speeches, contains a written record of his remarks before teachers that day:

“It is a source of pride to me that in my public service I was able to improve the salaries and conditions of the public school teachers by raising your pay, fixing its minimum and making your vacation leave commutable. And we are not going to stop there. Personally, I will not because I know that you are in the frontline of the great national brigade.”

His determination to see an educated Philippine nation underscored a narrative of modernization throughout his presidency. Today, the Philippine workforce is lauded for its English-speaking abilities along with their indelible pluck and drive to succeed. While infant mortality and rural poverty are issues today as they were then, the early 20th century Philippines was a rigid society with a racial class system inherited from Spanish colonial leadership over the course of 300+ years. The idea that a commoner, much less the son of a jail warden could be president was laughable to many. But his tireless efforts as an educator, and later as a public servant and leader of the nation, signaled a shift in the possibilities for anyone with a strong work ethic.

At Malacañang Palace, President Quirino’s remarks on June 17, 1953 stressed the importance of Philippine labor and industry as he signed the Magna Carta of Labor into law. He voiced his support for laborers and the strength of personal responsibility in growing the nation’s economy:

“You may not believe it, but this bill will spell success in our industrial program if carried out in the spirit and to the letter of the law. Of course, there is that human element, that human equation which must come in to complement or supplement whatever deficiency or insufficiency the provisions of this law may have, in order to adjust ourselves—management and the laborers—to conditions obtaining in particular localities.”

As our family prepares to celebrate Lolo Elpidio’s 125th birthday in the Philippines this November, it would be prudent to remember not just his accomplishments as a statesman, but also his egalitarian ideals as a Filipino who simply wanted the best for his people.

Constante G. Quirino is a writer and stylist based in Philadelphia. While primarily a fashion journalist, his writing ranges from personal narratives, historical analyses, to comedic monologues and prose poetry. He is co-author and co-editor of President Elpidio Quirino: Statesman & Survivor, to be released digitally in time for Elpidio Quirino’s 125th birthday celebration this month, with print on demand available.