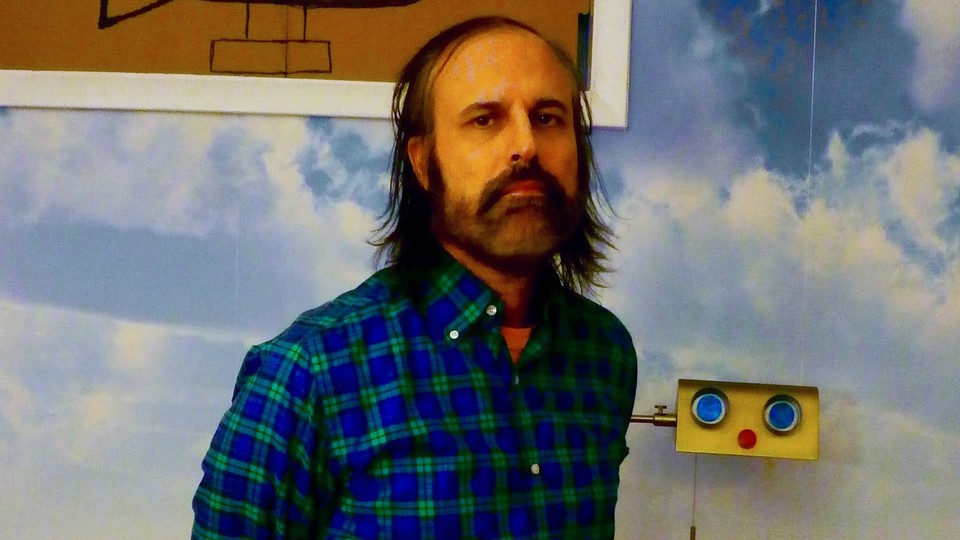

David Berman Saw the Source of American Sadness

The singer for Silver Jews and Purple Mountains brilliantly described how restlessness can curdle into isolation.

One early Silver Jews EP was named The Arizona Record, and another one, nearly a decade later, was Tennessee. After the singer David Berman’s death at age 52 last week, the albums that fans turned to included 1998’s American Water, with its lyrics about “Protestant thighs” and “blue, blue jeans,” and Purple Mountains, the self-titled debut of his new band, named for a commonly misheard line from “America the Beautiful.” That album’s songs mentioned New York City, Oregon, Chevrolet cars, and a “marketplace / In the wanting corner of a western state.”

Berman sang about America. He did not do this in addition to his other great themes—music, nature, beauty, death, drugs, disconnection—but rather as part of the same project. His songs could almost be described with the genre tag “Americana”; his life can’t be discussed apart from American political struggles. Parsing poetry as allusive and grammar-agnostic as his is never straightforward, but he said he wanted his music to be understood, and his take on America was plenty clear. Berman loved the nation’s sprawl and its myths, and he warned about the crushing solitude they created.

Born in Virginia and raised in Texas, Berman spent parts of his adulthood in Louisville and Nashville. Many of his onetime hometowns were mentioned in his songs—but not as much as he mentioned the idea of moving. “Sometimes I dream of Texas / Yeah, it’s the biggest part of me,” he sang on the first Silver Jews album, adding, “And the planes look like the sea at night / Oh, she wants to be so free.” Berman was paying tribute to a “rebel state” with those lines, but he was also pulling a typical move of his: pairing a vision of home with a pang of desire for escape. His lyrical obsession with place recalled the country artists whose music Berman evoked in his arrangements and singing style. But for him, location most often spelled dislocation. Places existed to be left behind.

Take 2001’s “Tennessee,” an uncharacteristically sweet-seeming take on country-western romance. The narrator courts a woman whose “doorbell plays a bar of Stephen Foster,” which is to say it plays 1800s minstrel tunes like “Oh! Susanna” or “Camptown Races.” He adds, “Her sister never left and look what it cost her,” and makes a plea for his beloved to migrate with him to Nashville, where he’ll start a music career. Here, too, was a story of home and not-home, of the settled being unsettling, and of flight as hope. “You know Louisville is death, we’ve got to up and move / Because the dead do not improve,” Berman sang. This perfect lyric was followed by a few more: “Goodbye users and suckers and steady bad-luckers / We’re off to the land of club soda unbridled / We’re off to the land of hot middle-aged women.”

There it was: the excitement, vanity, and flimsiness in the American dream of reinvention. Berman might have even bought into that dream. For all his disaffection, he was also ambitious; in interviews, he portrayed other musicians as competition and fretted about his own acclaim. His song’s narrators, meanwhile, feared they were only as good as their accomplishments—and that even success would fade. “Advice to the Graduate,” which appeared on 1994’s Starlite Walker, counseled, “Don’t believe in people who say it’s all been done / They have time to talk because their race is run.” On the twitchy “People” (1998), he and his sometimes co-writer Stephen Malkmus followed a mention of people going to the moon—that great national feat—with “People, be careful not to crest too soon.” On Purple Mountains, “All My Happiness Is Gone” used football as the all-American valorous struggle of choice. Referring to a joyous time long ago, Berman sang, “That was life at first and goal to go … All our hardships were just yardsticks then, you know.”

What happens to those who lose their races, or never get to run them? When searching becomes wandering? Is a life without ties really freedom? Berman’s music asked these questions. The title of American Water conveyed the instability on which the national dream floats, and its songs drew devastating, place-based portraits of isolation. For example: “My life at home every day / Drinking Coke in a kitchen with a dog who doesn’t know his name.” Or: “I dyed my hair in a motel void.” On “Blue Arrangements,” Berman and Malkmus lusted after the patrician set—“country-club women in the Greenwood Southside society pool”—but also said, “Sometimes it feels like I’m watching the world / And the world’s not watching me back.” “Federal Dust” listed locations—Malibu, Kansas City, South Dakota—and things that don’t happen there: “They don’t vote / They don’t even smoke,” and “They don’t cream / They don’t dream.” These were visions of stagnation distributed widely, or of the singer’s null empathy for the lives of others, or of both.

It may seem puzzling that American Water’s opening verse—the legendary beginning to arguably Berman’s greatest song—recalled him “slowly screwing [his] way across Europe.” Maybe the vowel sounds of Europe just sounded good there; maybe he was talking about an actual episode in his own life. Or maybe—this would seem an unconscionable reach if Berman hadn’t been known for sweating over every lyric—it’s only in Europe where he’d be “hospitalized for approaching perfection.” In America, perhaps he could have kept spiraling out, to the point where, as happens later in the song, onetime lovers would no longer recognize him. He could ride the roads that are “painted black … because people leave and no highway will bring them back.”

Diagnosing the nation’s soul-state is difficult without diagnosing its politics, and Berman wasn’t afraid to do just that. American Water’s “Smith and Jones Forever,” for example, described opportunism, impoverished cityscapes, and an electric-chair execution put on for a crowd. As time went on, his satires became clearer and bitterer. “San Francisco B.C.,” from Silver Jews’ final album (2008’s Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea) offered a madcap parable about countercultural types with “sarcastic hair” who attempt—and, in the end, fail—to resist capitalism. That album’s pining anthem, “Suffering Jukebox,” opened with a snapshot of money-chasing individualism reshaping the physical landscape: “Cranes on the downtown skyline is a sight to see for some / It ought to make a few reputations in the cult of No. 1.”

It was only after that album that Berman made his most dramatic political statement, though. In 2009, he dissolved the band and then revealed the identity of his father: Richard Berman, a corporate lobbyist infamous for ruthlessness and cynical media manipulation. In Berman’s farewell-to-Silver-Jews note, he referred to his dad as “a despicable man” and “a sort of human molester,” and said he was setting off to find some better way to fight back than with music. He then rented an apartment in sight of the Washington, D.C., home where his father lived during the singer’s childhood and got to work on a book about his father’s alleged poisoning of the American discourse. HBO offered to buy the rights to the story, but Berman declined, fearing the series that resulted might romanticize what he saw as his dad’s villainy. The book itself never materialized.

When he emerged with Purple Mountains this year, Berman told interviewers that he had spent much of his hiatus reading about politics, history, and religion. He also said that he and his wife had separated as a result of him becoming even more of a shut-in than he’d been before. In an interview with the Kreative Kontrol podcast, he mentioned that he had started making music again because he needed the money. Speaking to The Ringer he said, “I’m not convinced I have fans. In my whole life, I’ve had maybe 10 people who have told me how much my music means to them.” It’s an unthinkable statement, especially in light of the passionate, painful remembrances that have followed his death. But somehow he’d become disconnected from the people his music had connected with.

Berman’s new album had a jolly air and a bleak soul. Its closing song, “Maybe I’m the Only One for Me,”—situated “on holidays, in lonely haunts / At closing time, in restaurants”—resigned its narrator to eternal singledom: “I’ll put my dreams high on a shelf / I’ll have to learn to like myself.” That’s plausibly a hopeful message, but on Kreative Kontrol Berman said he was worried that it represented the “ultimate neoliberal love song, as we sit in a place of peak individualism … It’s not the kind of message I’m proud to spread.” Which is to say he worried that his expression of self-loathing could be heard as—or might even be—stoic self-affirmation. Here again, in his final song, he was both enthralled by a stereotypically American idea and disgusted by it.

Purple Mountains’ other descriptive scenes blended awe and contempt, too. Berman sketched a winter evening in New York City as a beautiful apocalypse. He leered, amazed, at the “magenta, orange, acid-green, peacock-blue, and burgundy” colors of the titular drink in “Margaritas at the Mall.” Then there was this verse, in “All My Happiness Is Gone”:

It’s not the purple hills

It’s not the silver lakes

It’s not the snow-cloud-shadowed interstates

It’s not the icy bike-chain rain of Portland, Oregon

Where nothing’s wrong and no one’s asking

But the fear’s so strong it leaves you gasping

No way to last out here like this for long

Sometimes Berman’s songs made it seem as though his sadness flowed from the land, and sometimes it seemed the land was his only solace. Self and setting can’t be disentangled, Berman knew. In a place where people dream of approaching perfection, its absence cuts all the more.