Angela Secchi was nine years old when she encountered Paul Strand for the first time. Now 73, she remembers being “scared of this very serious man who never smiled”. Strand approached her in her hometown of Luzzara in northern Italy, while she was on her way to “the fields nearby, where the adults were picking the grapes to make wine”. He was carrying a large plate camera and asked her to ask her parents if he could photograph her.

“I was a very shy little girl, a country girl,” she says now, smiling. “I had never seen a camera before and I remember thinking, ‘What is he carrying?’” The following day, she posed for her portrait. “My aunt wanted me to wear my one very nice dress, but he said: ‘No. No. No.’ He wanted me to wear something old and worn. Then he took my uncle’s hat and placed it on my head so I looked like a farmer.”

Angela eventually saw her portrait when Strand’s collaborator, the writer Cesare Zavattini, returned to Luzzara in 1955 to give a copy of Strand’s new book to everyone who was featured in it. Those who were not were given the chance to buy it, but no one did. “People were amazed because the book cost the same as a bicycle,” says Angela, laughing, “and back then, a bicycle was what everyone needed.”

Un Paese: Portrait of an Italian Village was the first important photography book published in Italy, and remains a landmark of postwar documentary photography. It is also perhaps the most powerful testament to Strand’s belief that photography could portray the lives of ordinary people, their hardships, but also their dignity.

The series Un Paese is one of the highlights of the V&A’s new show, Paul Strand: Photography and Film for the 20th Century. Perhaps the most iconic image in the series is The Family, a group portrait of a widowed Italian mother, Anna Lusetti, and five of her sons. The brothers are meticulously arranged around the front door of their family home, with Anna, the matriarch, at the centre. It is a study of familial strength, solidarity and intimacy that also suggests a life lived at considerable human cost.

“The mother told me about her family,” Zavattini wrote later, “how she had married at 18, how four of her children had died in infancy, how in the 20s her husband on two occasions had been clubbed and beaten by ‘unidentified political assailants’ … She is surrounded by five of her eight sons, each the veteran of a different campaign in the second world war, each a distant character, but each bound to the woman, the land represented by that home, that doorway.”

Strand was 65 when Un Paese was published and, by then, his restless creativity had taken him on a singular journey. Having helped define modernism alongside Edward Weston and Alfred Stieglitz, he abandoned the rigorous formalism that had characterised his earlier studies of New York for a more politically committed approach. Like many writers and photographers of the time, Strand identified with the radical left, and had come to believe in photography as a medium for social change.

To this end, he helped form the Photo League in New York in 1934, with the aim of “integrating formal elements of design and visual aesthetics with the powerful and sympathetic evidence of the human condition”. He later embraced film-making as part of the progressive collective, Frontier Films, shooting peasant workers in Mexico, before returning to New York to make documentaries such as the staunchly pro-union Native Land (1942). His stance inevitably brought him to the attention of J Edgar Hoover and, in 1947, the FBI declared the Photo League “subversive and anti-American”.

Unable to fund his films after the war, Strand returned to photography and published his first book, Time in New England, in 1950. It was a precursor of what was to come, both in its blending of images and writing, and its attempt to evoke a deep sense of place. Disenchanted by the anti-communist paranoia that prevailed in America, Strand left for Europe in 1949. He settled in France, where he made a study of rural life called La France de Profil, before becoming fascinated by Luzzara through his burgeoning friendship with Zavattini, an intellectual who had helped shape Italian neorealist cinema as scriptwriter of Vittorio De Sica’s acclaimed 1948 film Bicycle Thieves.

Luzzara, situated on a vast flood plain on the banks of the Po river in Emilia-Romagna, was Zavattini’s hometown. It was also a Communist stronghold, where the local partisans had fought a dogged war of resistance against fascists a decade earlier. Today, the streets around the centre of the quiet town still bear the names of 14 local men who were rounded up and executed just days before the liberation.

When Strand appeared in the town less than a decade later, as Angela recalls, “many people were wary of him because they thought he was a spy”. Even Valentino Lusetti, one of Anna’s eight sons, who was hired as Strand’s guide to the local countryside and its close-knit communities, briefly became an object of rumour and suspicion. In the Biblioteca Panizzi in Reggio Emilia, two hours’ drive from Luzzara, an extensive archive of photographs, postcards, notebooks and letters attest to the meticulous research and preparation that Strand and Zavattini undertook before the trip to Luzzara. The busy Zavattini did not actually work alongside him, but constructed the written narrative later. It includes exchanges with the writer Italo Calvino, as well as a list of proposed titles – Love in Italy, The Kids in Genoa – for an extended series titled Italia Mia, which would record everyday life throughout the country.

In Luzzara, Strand relied on Valentino Lusetti for his local contacts and fluency in English, which he had learned as a prisoner of war in America. Strand’s wife, Hazel, chronicled the project in images of her own. The Cultural Centre Zavattini in Luzzara has several of Hazel’s photographs of Strand at work, photographing a hat maker’s, a local Parmesan factory and a local cafe and its regulars.

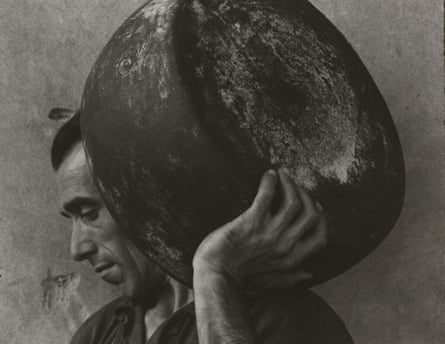

In the Parmesan factory where, in 1953, Strand made his modernist portrait of a worker carrying a huge sealed cheese on his shoulder, production is still thriving, but the town itself seems inordinately quiet on a wintry weekday in February. As I walk around, with Strand’s images of another time echoing in my head, I realise once more how ghostly a medium photography can be: the cafes, shopfronts and doorways that he photographed remain and are just about recognisable amid the modern signage. Old men still gather near the cafe by the main square, but Angela is one of only a handful of those photographed for the book who are still alive. Only the long, tree-lined arc of the river Po as it cuts through the flat plain seems unchanged.

“I will always be grateful to Strand for what he made me see about my own townspeople,” reflected Zavattini in 1981. More than 30 years later, they are even more affecting in their evocation of an Italian peasant way of life that has faded into history.

Paul Strand: Photography and Film for the 20th Century is at the V&A, London SW7, from 19 March to 3 July. Details: vam.ac.uk

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion