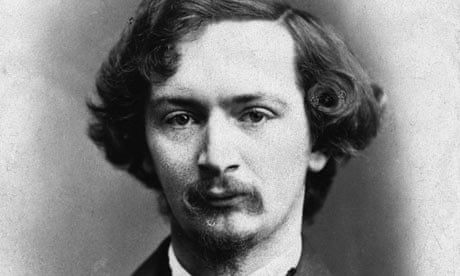

This year is the centenary of the death of Algernon Charles Swinburne, a fascinating writer whose range of subjects was unusual, even for the protean Victorians. "Anactoria", for instance, is a lesbian love poem in the persona of Sappho, tinged with the poet's own sadomasochistic predilections. However, in a series of roundels about babyhood he wrote as charmingly as any Victorian parent could wish. He was a self-styled Pagan and a genuine Philhellene, steeped in Greek mythology (and prosody): yet northern sea-coasts found a near-realist strain in him. "The sky, the water, the wind, the shore" are where his imagination seems happiest. He spent much of his childhood on the Isle of Wight, and frequently visited Northumberland, which he considered his ancestral homeland. Sark is the setting of some of his best sea-poems. I haven't identified the setting of this week's poem, "The Cliffside Path", but readers may be able to help out.

No one could deny that he is often guilty of pleonasm. He relishes those rhetorical devices based on repetition – polyptoton, for example, where the same word meets itself in a different grammatical form ("Wielded as the night's will and the wind's may wield"). His gift is not for narrative, or for thought (which is a kind of narrative); the final stanza here shows up a poverty of argument. But it isn't true that he fails to register the world around him. Mood and music and observation are simply rolled into one.

Edward Thomas, in many ways his poetic antithesis, wrote some of his finest criticism about Swinburne, alert to the flaws while allowing the felicities. Of that favourite anthology piece, the first Chorus from the verse-play, Atalanta in Calydon ("Before the beginning of years/ There came to the making of man/ Time with a gift of tears,/ Grief with a glass that ran"), Thomas commented: "This … has the appearance of precision which Swinburne always affected, which is nothing but an appearance." In the context, Thomas has identified a flaw – but look beyond the context, as the generalisation "always" invites us to, and the statement seems to shed even greater light. It could almost be a definition of the art of the Impressionist painters ("the appearance of precision"). Think of Swinburne as an Impressionist poet, and you begin to understand his strange mimetic gift.

In "The Cliffiside Path", he draws on his characteristic rhetorical devices, but the verbal accumulation isn't just "music": it produces a memorable seascape. The triple runs of adjectives in lines three and four are brilliantly effective brush-strokes. There is considerable detail in the descriptions of the broken path, the collapsing cliff, the "ridged and wrinkled" strand (both epithets earn their place). The multiplicity of words and phrases used to evoke the erosion he is lamenting ("flawed", "crumbled", "rent", "riven", etc.) suggests not so much vagueness or imprecision as an attempt at recording an intricate messiness. What looks at first like a romantic, wordy flourish, that "pulse of gradual plumes through twilight wheeled", possibly describes the fan-like cloud-formations of a fading sunset. Not that he avoids all literary gestures – note the old word "twiring", from "twire", to peep or glance, pronounced to rhyme with spear. Literary, yes, but certainly more effective than the clichéd "peep".

There's a great deal of movement in the poem. Its form, a variant of the French form Swinburne particularly favoured, the Ballade, is the Ballade Supreme, with its 10-lined stanzas and five-line envoi. Swinburne's choice of such forms is all of a piece with his love of repeating grammatical constructions, those mirrors and antitheses that create a swirling or to-and-fro motion. Here, the refrain brings us back to the inevitability of the process he is describing. Its circular movement is appropriate. And, through it all, you seem to hear the sea-wind gusting and punching out those hexameter lines: "Wind is lord and change is sovereign of the strand."

The Cliffside Path

(from A Midsummer Holiday and Other Poems, 1884)

Seaward goes the sun, and homeward by the down

We, before the night upon his grave be sealed.

Low behind us lies the bright steep murmuring town,

High before us heaves the steep rough silent field.

Breach by ghastlier breach, the cliffs collapsing yield:

Half the path is broken, half the banks divide;

Flawed and crumbled, riven and rent, they cleave and slide

Toward the ridged and wrinkled waste of girdling sand

Deep beneath, whose furrows tell how far and wide

Wind is lord and change is sovereign of the strand.

Star by star on the unsunned waters twiring down,

Golden spear-points glance against a silver shield.

Over banks and bents, across the headland's crown,

As by pulse of gradual plumes through twilight wheeled,

Soft as sleep, the waking wind awakes the weald.

Moor and copse and fallow, near or far descried.

Feel the mild wings move, and gladden where they glide:

Silence, uttering love that all things understand,

Bids the quiet fields forget that hard beside

Wind is lord and change is sovereign of the strand.

Yet may sight, ere all the hoar soft shade grow brown,

Hardly reckon half the rifts and rents unhealed

Where the scarred cliffs downward sundering drive and drown,

Hewn as if with stroke of swords in tempest steeled,

Wielded as the night's will and the wind's may wield.

Crowned and zoned in vain with flowers of autumn-tide,

Soon the blasts shall break them, soon the waters hide,

Soon, where late we stood, shall no man ever stand.

Life and love seek harbourage on the landward side:

Wind is lord and change is sovereign of the strand.

Friend, though man be less than these, for all his pride,

Yet, for all his weakness, shall not hope abide?

Wind and change can wreck but life and waste but land:

Truth and trust are sure, though here till all subside

Wind is lord and change is sovereign of the strand.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion