When I walked in the room, they were all dancing. Eric Dolphy wheezed from the speakers like an asthmatic who’d just snorted up five Benzedrex inhalers in one go. And the horde danced on, half a dozen or so bodies flicking their limbs around in a late-’70s variant of zoot suit be-bopping. The ghost of Charlie Parker’s exhausted frame lives on in Bristol, carefully tended by the Pop Group and their Saturday morning constitutional.

Two weeks later, the photographer arrives in the same room and the same dance is being performed. Is this how they spend all their spare time or is it an initiation ritual for the first-time visitor to their communal meeting-place-cum-informal-office, this shabby but chic ground floor flat in a not very well preserved monument to the solidity of Victorian house building? Has be-bop suddenly become the new cult? Or is this their way of saying, “This is us. This shows you how we’re different”?

Later, by way of an answer, they react with near venom to the very mention that they’re a ROCK BAND. “Yeeeeeeeuuuugh”, chorused by five temporarily indivisible mouths.

On the train down to Bristol, I talked over their history with manager Dick O’Dell, who looks like a weasel, wispy-blonde moustache and all, but acts more like a mother cat determined to protect his five occasionally errant charges.

I’ve known Dick for some time now. First as Alex Harvey’s tour manager, then performing the same wet-nurse duties for the Stranglers. His current occupation must seem like the world’s biggest doddle after attempting to sort out life on the road for those prima donnas.

With the Stranglers, he’d become an exhausted imitation of a human being. You could have stripped his skin from his flesh and used it to print this paper. Tired of their childish excesses, he remembered the only band on the Stranglers’ British tour who’d survived the savage “welcome” that the Stranglers’ fans gave the support act – the Pop Group on the Bristol whistle stop.

“The audience didn’t like them. But they didn’t try to stop them. They didn’t shout and throw things like they did everywhere else. They just didn’t know what to make of them. And I thought anybody who can get that kind of reaction has got to be special.”

Their marriage was cemented over a year ago now, but the Pop Group have paced their emergence from their Bristol universe with almost unknown slowness. Part of the reason was that most of them were still at school – last spring I heard they were signing to Radar and asked Andrew Lauder what was taking so long: “We’re waiting till they’ve finished their A-Levels”.

*

And only now are they preparing for the release of their first album and the move into more regular live appearances. They were, above all, concerned to do everything in a way it hadn’t been done before (or, at least, a way that they hadn’t seen or heard it done before). With admirable magnanimity, they donated the proceeds from their first high-profile tour to Amnesty International, the organisation that helps prisoners of conscience the world over and an organisation whose liberal ethos and Jesuitical structure is a close parallel of the operational philosophies and methods of the Pop Group themselves.

Talking to Dick, I felt that, as much as anything else, he was involved with the Pop Group because he was looking for them to combine what he’d hoped to find in both SAHB and the Stranglers – SAHB’s onstage almost megalomaniac completeness and the Stranglers’ totally megalomaniac social concerns.

Dick talked about Jean Jacques Burnel. “I agree with a lot of what he says. Like he’s preparing for the collapse of society into chaos. When it comes he’ll be ready. He’ll retreat into the mountains with the Finchley boys. They’re like a warrior clan. He’s right about society collapsing. Only I don’t think it’s gonna happen quite as soon as he does.”

If JJ is preparing for the collapse, the Pop Group act like it’s already happened. Entering their company in Bristol is like happening on a post-apocalypse commune almost blissfully unaware that the world has any other survivors. They are concerned with the outside world, with their potential audiences but, for all their assertions that they only question, never state, they’re undoubtedly a tight-knit group of confusedly motivated men.

Andrew Lauder: “The Pop Group are not content with being quite successful. They want enormous success. They’re so convinced and certain of what they’re doing that I actually find them awe-inspiring.”

Also very funny at times. Apart from the obvious irony of their name – what Pop Group would write a single called She Is Beyond Good And Evil? – most written reports of them have stressed the serious, thoughtful side of them, rejecting the aspect of them that leads them to be jumping around a small room on a frosty Saturday, exchanging their own jokes, which are mostly so in-group that even sitting right there with them, I have no idea what they were on about. Still, it’s a course they choose to steer themselves. When I met Mark informally a few days before at Dick’s place, he provided an instant review of the film he’d just seen – Jean Genet’s Chant D’Amour, an intense and nightmarish little French number – that would have kept Clive James in witty comments for couple of TV shows and half a dozen columns. Yet, when they sit down to do the interview, they are mostly very serious, the relieving humour being of a rather infantile kind – they suggested we did the interview in a public convenience; the sound’s better in there.

*

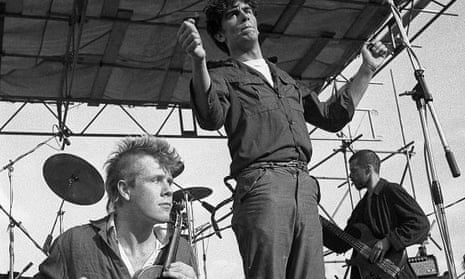

The Pop Group are: Mark (Stewart) – vocals, Bruce (Smith) – drums, Gareth (Sager) – guitar, Simon (Underwood) – bass, John (Waddington) – guitar. They are invariably referred to by their Christian names alone. They all talk at once, making the transcription of the tape almost torture-like. What seemed like extended discourse at the time turned out to sound as fragmentary as their music. Starting off at a high pitch of confusing (to me) badinage, sparks of verbal disagreement flying between them, they slowly wound down till only Mark sounded at all awake. It wasn’t like an interview at all. It was as if they used the opportunity to engage in a catharsis of their own thoughts. Fragmentary it was, so fragmentary be it. No idle banter about other music, just a manifesto-like joint discourse, so welcome to the Pop Group’s view of the universe and plans for their intervention in it.

Mark shows me the projected album cover photo, a Don McCullin picture of a tribal gathering in remote Africa. I wonder how it links up with them.

“I don’t know … pretty symbolic … can’t really explain it. It fits with the kind of general feel.”

Bruce: “We’re doing everything with the same approach, if you can call it an approach.”

So who decides the approach?

Gareth: “It’s just a total combination of ideas, really.”

Mark: “We only actually do something when everybody’s totally into it sort of. You just need the others to agree, you know.”

Dick had told me that one of the tracks on the album, Boys from Brazil, was closely connected to the book of that name.

Mark: “No … Dick just lies to everybody … I didn’t really take the title … well, I did, er, jubjub, [few more seconds of attempts to start sentence] ... I don’t know really. The songs speak for themselves if you see what I mean. I don’t want to explain them because … it’s not anything particularly to do with the book, but it might be. It’s up to people when they hear it.”

Bruce: “Variety’s the spice of life.”

Mark had previously told me that he didn’t want to copyright his songs.

“I was just thinking it would be a good idea if you didn’t copyright it, so that if people wanted to do them, they don’t have to go through all the hassle, you know. We have difficulty using photos and stuff because of people’s copyright on them. I just thought it’d be easy if we didn’t have a copyright on it.”

There is indeed no composer, credit or copyright on the single.

Bruce: “The thing about copyright is that it separates people [a flute starts playing quietly in the background]. It means that if there’s something you appreciate, that you like and you wanna make it part of you in a way, you can’t, you’re stopped from doing it. It keeps people apart. It keeps people from getting together in some way. It’s another one of those things that keep people separate.”

Mark [almost snorting]: “Patenting your ideas that they’re mine and no one else can have them.”

Gareth: “Cos it’s not art, you know. It’s for everyone else, for everyone else to do what they want with.”

Simon: “Most of the music is because we’ve heard music before and we’ve picked up things from other people … no possession about it.”

An unusual attitude.

Mark: “No, it isn’t.”

Bruce: “Yeah, it should be a pretty common one, really.”

Mark: “People are so used to having to say, ‘That belongs to me’ because they have to cope with the fact that everybody’s trying to grab something all the time … One of the main things we want to do on the tour is to smash the barrier between performer and spectator. We wanna try and get audience participation. Maybe we’d like to play without stages and stuff so instead of somebody living out the excitement of somebody and somebody else being a vegetative spectator, we wanna get a whole thing going. Otherwise it’s like going to see the film where other people are living out the excitement for you.”

Simon: “Sometimes that’s a good way of … of …”

Mark [sharply]: “Perhaps.” [Softer] “Cos the whole idea is not for us to say, ‘We’re great, we’re doing this’, it’s to kind of inspire people, y’know, and get people buzzing with energy so they can do stuff as well, realise their potentials.”

Bruce: “There doesn’t seem to be any reason to me why we should be on that stage.”

Simon: “You can get that point across anyway, but lots of people get annoyed if we’re all on the same level and small people can’t see the band.”

Mark: “People … not better than anybody else, just people sharing things with people … not having any gaps whatsoever. Otherwise it’s a kind of blind faith thing, this religious worshipping of figureheads … I personally don’t know why people are more interested in our ideas than anybody else’s.”

Gareth: “It’s not thinking they’re as important as us. It’s thinking they’re as unimportant.”

Bruce: “We haven’t got any solution to offer. We just know there’s something wrong somewhere. We can’t sit here and say we’ve got it all worked out. We’re not gonna tell you what to do. I can’t say that I’m right or that he’s right or that you’re wrong.

“The only position we’re in at the moment is we’re getting some vague idea of what the questions are. Which ties in with the Y [the title] of the album. We can’t take any stances on the stuff. We deliberately contradict ourselves.”

Mark: “… being part of a society you don’t want to have anything to do with. We’re one of the strongest parts of the whole consumer society and we don’t want to have anything to do with it.

“The lyrics throw up ideas but they don’t take particular stances, they deliberately contradict themselves. Cos although you might think you’re doing something good, you’re just keeping the whole fucking thing going … like social workers or stuff.

[Signing to a big record company] “That’s not specifically for us … [quietly with a manic chuckle] … we’re not really enjoying it.”

Bruce: “We don’t want any of their royalties. They can keep all their money as far as we’re concerned … honestly.”

Gareth: “We’re not trying to destroy anything. We don’t really know what we’re trying to do. We’re just questioning everything.”

Bruce: “It would be good if we could have more personal interaction – like arguments. A conversation is much better than listening to a record cos you can actually argue back a point. If people think we’re full of shit, they should come and tell us.”

Mark: “They can write to us. That’s why we’ve put the address on the sleeve.”

Hopes for the album?

Bruce: “Maybe that people will listen to it and just check it against virtually every idea they have in their head, every idea they have about everything.”

Mark: “I don’t see why people should have their life laid out for them into a set job. They have about five choices from a careers adviser. They don’t train people to be human beings, they train them for certain functions. I wouldn’t like to think I’m a singer. I’d like to think I’m everything. I wouldn’t like to think I’m one function and I’m only gonna be one function till I die and that’s it and I’m dead and that’s all I’ve ever been.”

The album itself. Originally it was to be produced by John Cale with a reggae engineer. Finally, Dennis Bovell of Matumbi took sole charge.

Simon: “Cale … yeah ... then we met him and we don’t wanna ever see him again, a totally self-indulgent pig.” (This is the only remark of the day that criticises someone apart from themselves.)

Bruce: “Dennis said it was like music he used to dream about.”

Dick: “It’s a question of balancing the in-going and the outgoing.”

Mark: “People that hate other people are people that are really well off. I can’t hate someone. He’s just as fucked up as we are. [Mark sounds drained, exhausted.] It feels nice when people are relaxed with each other but ... I don’t feel happy about things in gen … ”

The tape shut off.

© Peter Silverton, 1979

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion