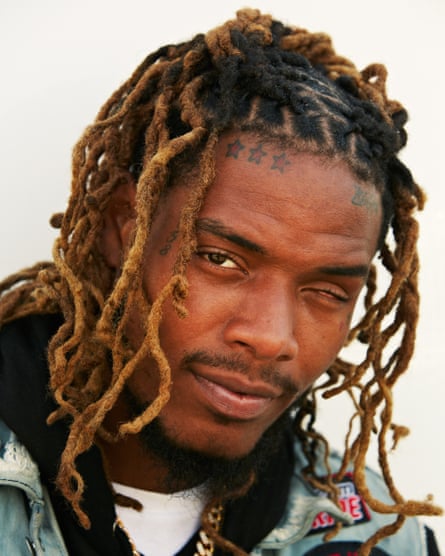

Fetty Wap lost his left eye before his first birthday, the result of congenital glaucoma. Nowadays, the vacant space is bloodshot when he lifts his eyelid, but it usually just looks as if he’s squinting from smoking too much weed.

During childhood, however, classmates were constantly making fun of the boy born Willie Maxwell II, provoking him into fights. As an elementary school student in Paterson, New Jersey, he says, he regularly brawled, once even throwing a desk at another kid. But he gradually became more comfortable with his disability, and as an adolescent abruptly decided one day to remove his prosthetic eye.

These days, at 24, he is fully comfortable in his skin, and has become as ubiquitous as anyone in hip-hop since emerging on the scene last year with his hit Trap Queen – a love story set in a crack house. He’s more melodic than Future, to whom he is often compared, grittier than Drake, with whom he has collaborated, and, his drug-dealing days now behind him, a better public citizen than his imprisoned idol Gucci Mane. Kanye West gave him some important early support last year, but Wap is much less likely to stick his foot in his mouth.

In fact, Wap would just as soon skip interviews altogether, although I get a chance to pick his brain in early April before the iHeartRadio Music Awards at the Los Angeles Forum. Inside the trailer he is sharing with Chris Brown, he has just finished smoking a joint, and is in a good mood. “I heart weed,” he snickers, posing for a photographer. He is soon reminiscing about his five-year-old boy Zoovier (who is now old enough for Wap to call when he is on the road) and his one-year-old daughter Zaviera (with whom he once made it rain cash at a New Jersey mall). His publicist, however, lets it be known that he’s not interested in talking about his brand-new baby girl, Khari Barbie Maxwell, born to Masika Kalysha, star of reality show Love & Hip-Hop: Hollywood the week before. (Though Wap visited mum and baby at the hospital, he has yet to publicly claim the child.)

It has been a whirlwind for the ascendant MC, whose love songs and tough raps are as unusual as his personality. He has got little polish, and maintains eccentric habits such as riding quad bikes at high speeds on New Jersey streets and pavements. While most rappers will while away an afternoon talking about their influences and hip-hop heroes, Wap has little regard for many besides Gucci Mane – whose alter ego Guwop informs Fetty Wap’s moniker (“Fetty” means “money”). New Jersey has a rich hip-hop history; Lauryn Hill and Jay Z are among those to have called it home, and the genre’s first hit, Rapper’s Delight, was created there.

But Wap is unfamiliar with that song; in fact, he has been rapping for only about three years. It’s all the more extraordinary, then, that he has been on a nearly unprecedented roll when it comes to lighting up the US charts. Which all raises the question: how did the bullied and broke Willie Maxwell II become celebrated hitmaker Fetty Wap?

Wap’s first exposure to performance came while banging the drums in the band at his childhood apostolic church in Paterson, called Solomon’s Temple. His dad played keyboards, his brother played bass, and his uncle was the lead drummer. “You had to get nice to play on Sundays,” Wap says, and his uncle made him practise diligently until he got up to speed. Wap played in his high school band, too – until he got into another fight and broke his hand.

His teen years were a mess; he dropped out of high school and began dealing drugs. At one point, practically homeless, he slept on friends’ floors. “I didn’t even get to use no bed,” he says. “I was lucky to have a carpet.” What little funds he had, he squirrelled away after his son was born to make sure he could support him.

Once he and his longtime friend Monty – who has featured on many of Wap’s tracks – started rapping, they quickly began taking things seriously. Hip-hop, it became clear, was an escape route from their dire circumstances. They trawled for beats on a site called SoundClick, rapping demos over instrumentals they found there. “We used to surf through there all day, listening to beats,” says Monty, whose real name is Angel Cosme, and who is as animated as Wap is low-key (what they share is a love of facial tattoos).

Wap found the beat for Trap Queen online, courtesy of an unknown Belarusian producer named Tony Fadd, who posted it on his website. (Fadd barely speaks English, but they later linked up to work out a royalty-sharing agreement.) Wap’s camp brought the beat to a New Jersey producer named Brian “Peoples” Garcia, who touched it up, and before long Wap made a rough cut of Trap Queen. He still remembers the snowy day in December 2013 when he first played it to Monty, in the unfurnished Paterson apartment where they were staying. “I was like, ‘This gon’ be the one that’s gonna get us where we need to be at,’” Wap remembers.

Monty was impressed, but an affiliate named Nitt Da Gritt was blown away. “When Gritt heard it he was on the phone, and he was like: ‘Yo, I’m gonna call you back!’” Wap says. Gritt runs the independent label that gave Wap and Monty their start – RGF Productions, meaning “Real Good Fellas” or “Rich Good Fellas”. Gritt told Complex that Wap had originally titled the song What’s Up Hello, but that Gritt made the decision to call it Trap Queen instead.

Wap became obsessed with the track, refining his combination sung-and-rapped delivery until it was time to officially record it in March 2014. Trap Queen got radio play in New York later that year, but received its biggest boost when it came on to the radar of a new record label called 300, co-founded by a crew of Warner Music Group alumni. The label saw the track bubbling online and tracked down Wap for a meeting. In person, he charmed 300’s Todd Moscowitz. “I told him: ‘I know you already rich, but if you give me a chance I’m gonna make you a lot richer.’”

Trap Queen almost single-handedly launched 300, and Wap’s fortunes as well. Telling the story of an ex-girlfriend – a ride-or-die type who was ready to go to jail for him – it’s a singular song, immediately striking for its slightly alien, Auto-Tuned melody and sweet-yet-gritty story. “I can ride with my baby / I be in the kitchen cookin’ pies with my baby,” he sings. It has found fans in all corners, many of whom have no idea what is meant by “the trap” or “cooking pies”. (Answer: the location and method, respectively, of preparing crack cocaine.) The lyrics are so seemingly innocuous that a pudgy, 10-year-old white boy from Tennessee named George Dalton made a popular PG version of the song without changing all that many of the lyrics. Trap Queen is now approaching half a billion YouTube views.

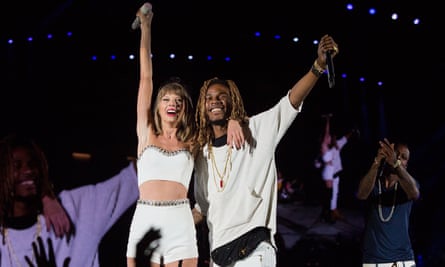

When Trap Queen broke, it seemed Wap might be a standard-issue one-hit wonder, arriving from nowhere and presumably headed quickly back there. But he soon followed up with a pair of top 10 Billboard hits, 679 and My Way; three more songs charted as well. His ascent has been so fast that he went from handing out free copies of his songs outside the 2014 BET Awards in Los Angeles to closing out the 2015 incarnation of the show onstage. In August, Taylor Swift brought him onstage at her Seattle concert and the pair performed Trap Queen together.

Still, not everything has changed. Accustomed to dirty money, Wap still deals in cash, stashing his savings in various nooks and crannies, rather than in a bank account. “At the end of the day, if the bank freeze, the cash won’t,” he insists.

He is now focused on helping the careers of collaborators such as Monty, who is in the process of putting together a solo album. But Wap has so many crew affiliations that it’s hard to keep track of them all. He and Monty are part of a music group called Remy Boyz, named for their former preferred drink, Remy Martin 1738 Cognac (though Wap now prefers Patrón tequila). Wap also has another music crew of his own called Zoo Gang (“Zoo” referencing the wild, untamed urban streets of his hometown), and GHB Zoo is the collective with whom he rides ATVs and dirt bikes. GHB stands for Go Hard Boyz, a biking crew that originated in Harlem and has taken Wap under its wing. Though ATVs are “all terrain vehicles”, Wap’s crew doesn’t do off-roading because, well, their areas don’t have much in the way of accessible wooded trails. But he notes that urban riding crews tend to keep kids off the streets and reduce crime; indeed, a bodyguard standing outside his Los Angeles trailer wears a shirt reading: “Bikes Over Bang ’N”.

Riding ATVs has become Wap’s great passion; not long ago he obtained a tricked-out Yamaha Banshee quad bike. With its twisted chrome, it resembles something out of Mad Max, and can go up to 70mph, members of his crew tell me. Wap suffered a motorcycle accident last year, and aggravated his knee filming a segment in advance of the iHeartRadio Music Awards on a quad. But shortly before the awards are scheduled to begin on this April day, he’s feeling better and ready to perform. Clad in a jean jacket and a shirt with American flag-coloured stars on his arms, he looks like a hip-hop Evel Knievel.

It may seem unlikely that a guy with one eye could inspire people by driving an obscenely loud ATV at high speeds, but that is Wap. He is the guy nobody saw coming; the one nobody thought would stick around. Having helped bridge the gap between the trap and the mainstream, he is a star who didn’t have to recast himself in order to succeed.

Fetty Wap plays the O2 Institute, Birmingham, on 27 May and Hammersmith Apollo on 29 May. He returns to the UK to play the Reading and Leeds festivals on 26 and 27 August.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion