“Most of the cast and crew were going out raving,” says film director Wiz. “There were some days on set when people hadn’t been to bed.”

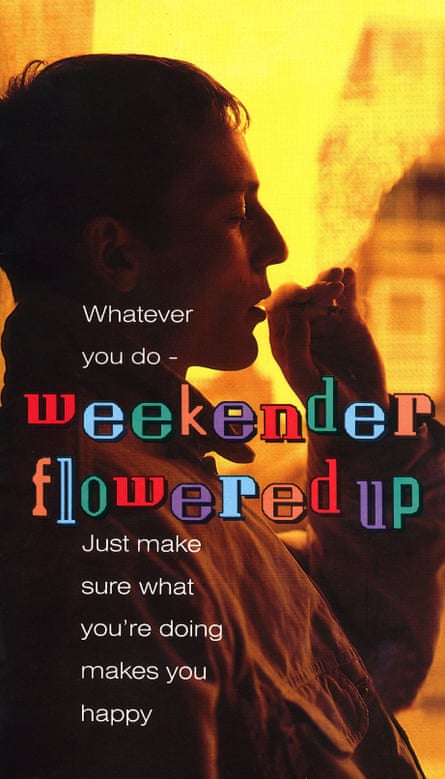

He’s talking about an 18-minute film he made for Flowered Up, an acid-house influenced band synonymous with hedonism. Though made to accompany their 1992 song Weekender, it was more than just a music video. “Without Weekender there would be no Trainspotting,” Danny Boyle has said. Such has been its influence that the film is the subject of a new documentary – I Am Weekender.

As an aspiring young film-maker, Wiz (AKA Andrew John Whiston) was involved in the acid house scene and desperately wanted to translate what he felt was a radical awakening into some kind of visual expression.

He’d already worked on music videos for Happy Mondays and Manic Street Preachers, but when he was played Weekender he heard the opportunity to create something that could crystallise a moment. “It was like my prayers had been answered,” he says. “It was a gift from heaven – like Moses coming down from the mountain.”

The film, which starred Lee Whitlock and Anna Haigh, set out to be a raw depiction of a weekend of clubbing – drug taking, sex, comedowns – juxtaposed with the grinding monotony of working life. It was a cinematic reflection of a song that took aim at the commercialisation of acid house. “That’s why Weekender, as a song, was so innovative,” says Wiz. “It was the first expression from ecstasy culture which was taking a critical look.”

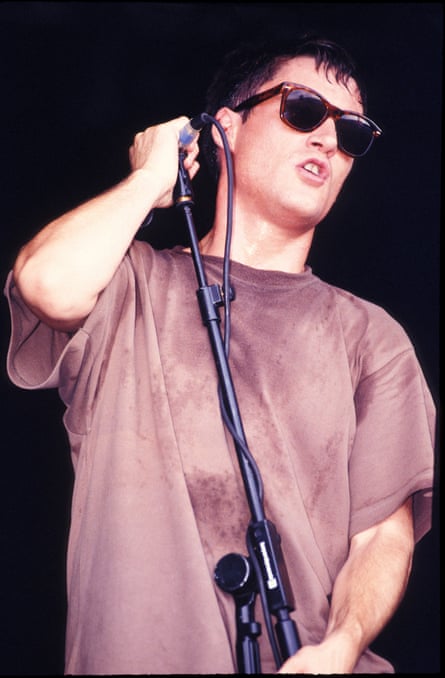

The band’s singer Liam Maher, along with its co-founder and manager Des Penney, had committed themselves evangelically to the party lifestyle. This pair of council estate kids from London took it as an affront simply to dabble in acid house part time. Penney believes that he and Maher went out every single night for two years from 1988-90 – something he viewed as a militant dedication to the cause.

The film’s unique pairing of stark realism with cinematic flair resulted in something that was “ahead of its time in terms of film-making, content and frankness,” according to Wiz. It was swiftly banned by the BBC and ITV and awarded an 18 certificate. Over the years it disappeared, seen only by those who had managed to get hold of a briefly distributed VHS copy. “It’s a cult film by anyone’s definition,” says Wiz. “It was not easily accessible.”

However, it’s clear from I Am Weekender, that its reach was still significant. Lynne Ramsay, Jeremy Deller, Irvine Welsh, Róisín Murphy, David Holmes and Bobby Gillespie all wax lyrical about its impact. Shaun Ryder declares it a “mini masterpiece”, while director Adam Smith says it went on to influence 00s teen drama Skins.

I Am Weekender was a lockdown project initially intended just to be Zoom interviews for a DVD extra feature. But when Wiz and musician Chloé Raunet reconnected at DJ/producer Andrew Weatherall’s funeral, and Raunet stepped in as a first-time director, she saw the potential for a documentary focusing on its importance.

By the time Weekender was made, Flowered Up were in trouble. They’d released two singles, then signed to London Records for an outrageous sum, including a £250,000 advance. They were hyped to such a degree they landed NME and Melody Maker covers before they released their debut album, 1991’s A Life With Brian, which when it emerged did little to justify the hoopla. For some band members, party drugs gave way to heroin.

But when they wrote Weekender there was a glimmer of hope. “It took a week to record but we knew we had something special,” says keyboardist Tim Dorny. It shifts from bursts of razor-sharp guitar, groove-locked basslines and yelping lyrics that excoriate the part-time raver of the title into a slumber of tranquil beats and woozy saxophone. A little like staggering back and forth between the main and chill out room in a club, within a song.

London Records refused to release it in its full 13-minute form and the band refused to do a radio edit so they went to Heavenly Records. Weekender reached the Top 20, was remixed to perfection by Weatherall, and remains the band’s defining, singular masterwork.

The band celebrated in typically Flowered Up fashion. Barry Mooncult, the band’s dancer worked as a glazier and cut himself a pair of keys to an empty mansion he was working on. The band moved in there for a week-long drugs bender. They strutted about naked in top hats they found in the wardrobes, lorded it up in a jacuzzi, and made plans for a monster party.

They booked DJs Paul Oakenfold and Terry Farley, sold a thousand tickets and held a rave that was “berserk” according to Penney. Everyone from Hanif Kureishi to Kylie Minogue was said to have been there. Sofas ended up in swimming pools and staircases were pulled apart. “The whole place was properly wrecked,” Penney says.

Weekender had revived Flowered Up’s fortunes. “We honestly thought it was the beginning of the second phase,” says Penney. But drug habits, deteriorating relationships within the band and the drying up of major label money signalled the end. “The concerns of real life got too much for everybody,” says Penney. “Rather than deal with stuff, most buried their heads in the sand.”

The lead role in the Weekender film was initially written for Maher. “He had the good sense to turn around and say to me: ‘This breaks my heart but I know that I will let you down during shooting because of my situation,’” recalls Wiz. “Liam could have gone on to do some extraordinary things. The tragic irony is he arguably became what he was railing against: numbed and bitter.”

The band attempted to reform in the 2000s but it foundered due to familiar issues. Maher died of a heroin overdose in 2009 aged 41. His brother Joe, guitarist in the band, followed three years later, also due to heroin. In 2018 Claudia Fontaine, who provided volcanic backing vocals on the song, also died. And just days after finishing the edit on I Am Weekender, Whitlock died of cancer.

“It’s almost like: is there a Flowered Up curse?” asks Penney, who is sober today. “It’s mad how so many people associated with such a thing can pass away. Looking back, I feel very proud I gave birth to it but it’s bittersweet. It’s a shame that we weren’t able to go and put our stamp on the world a little bit more.”

I Am Weekender will premiere at the Glasgow film festival, 11 and 12 March. Special screenings and the Blu-ray arrive in June.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion